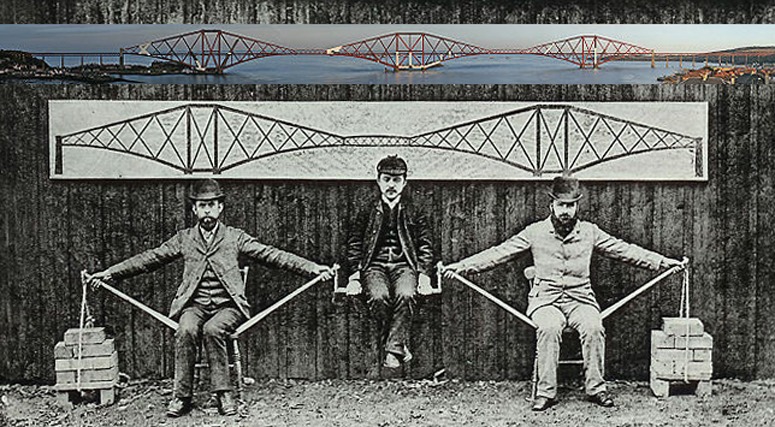

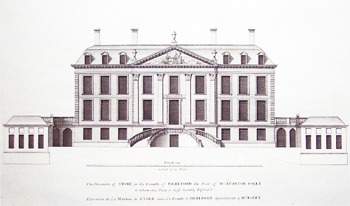

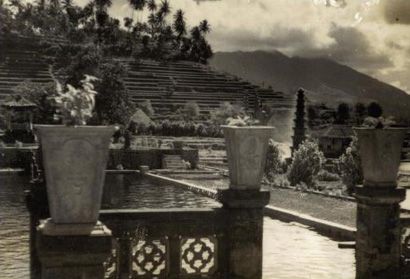

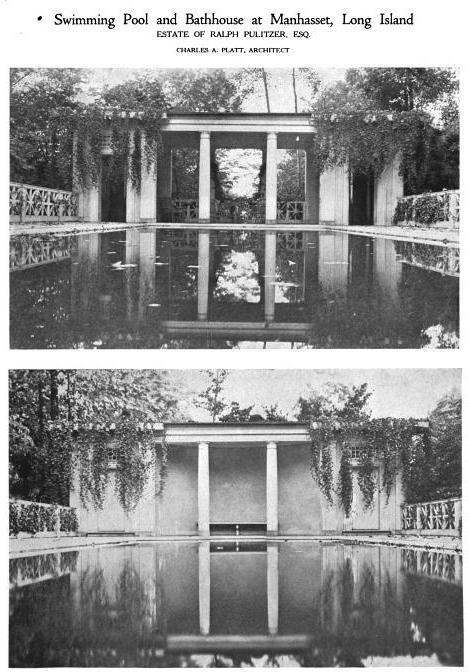

As the above and below photographs show, it is a good idea to test ideas at the small scale and the human scale before building them at full scale. This also applies to city building: ideas should be tested at the garden scale before being built at the city scale. There are three advantages to this procedure. First, city building is immensely complicated and therefore requires even more testing than engineering design. Second, working with garden-scale models creates an opportunity for piecemeal planning, working from details to generalities and from small to large (see post on gardens and landscape urbanism). I argued for this in an essay on The Tradedy of Feminine Design and, though not happy with the method being described as ‘feminine’, I remain convinced that the small-to-large design process is a necessary counterweight to the far-too-popular Master Planning approach. It is also very well suited to the garden-and-landscape way of thinking. Detail decisions can be conceived as planting ‘seeds’ which will grow into cities. This is, let us not forget, both the way most of the worlds cities began and also the way they have grown. The third advantage of using gardens as laboratories for city design is that gardeners always and instinctively deal with ecological, hydrological, recycling and climatic issues.

Above photo of wind tunnel testing of a model of a plane courtesy QinetiQ Group.