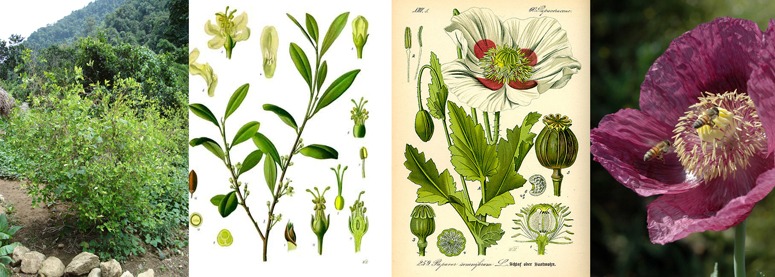

Growing Papaver somniferum (right pics) in your garden is legal in the UK but not in the US. Converting it to opium or morphine is illegal in both countries. Erythroxylon coca (left pics) is the source of cocaine, which was a legal ingredient in Coca Cola until 1903. Opium was banned in China, in 1799. The British fought a war to have it re-legalised, which happened in 1860. The disadvantages of opium and cocaine are well known but, one wonders, might their worldwide re-legalisation bring any advantages? Yes: (1) the wicked drug dealers would be put out of business (2) recreational drugs could be taxed, like alcohol, to raise government revenues (as American states are increasingly doing with sales taxes on cannabis) (3) the US and UK prison populations, as examples, could be halved (4) the Taliban could be put out of business and the coalition of the increasingly-unwilling could withdraw from Afghanistan and stop smashing up ancient villages with Predator drones (5) innocent drug users would not be poisoned by impure contaminated drugs (6) countries like Columbia, Bolivia, Brazil, Peru and Mexico would benefit from the demise of their drug cartels, criminal gangs and private armies – the drug trade is immensely harmful to civil society in the producer countries (7) sex workers with a drug habit to fund could turn to healthier and more productive occupations (8) crime could he halved, because funding drug purchases is the predominant motive for property-related crime (9) police relieved from ‘the war on drugs’ could prevent more socially harmful crimes – and police corruption would be reduced (10) with fewer wars to fight, the US and the UK could begin to re-rebalance their budgets.

My own experience of taking dangerous drugs is as follows (1) smoking – and inhaling – tobacco as a student (2) limited use of orally administered alcoholic drinks as an adult (3) I was once given a marijuana joint. If it contained any of the illegal substance I did not notice the effect. But the scene is engraved in my memory. Mustafa, a girl and myself were at the top of a deserted Roman amphitheatre at midnight. The mountains to the north and the glittering sea to the south were bathed in moonlight. We laughed a lot and our voices rang round the marble amphitheatre. The location (Side, Turkey) is shown in Sean O’Sullivan‘s photograph. Though I did not become addicted to drugs, I did acquire a serious lifelong addiction to ancient sites, beautiful landscapes and laughter. Since this blog post is published on Christmas Day, it is worth remembering that the date of Christmas probably derives from pagan celebrations of the solstice (eg the Roman Saturnalia) and that sacramental wine is used at Mass.