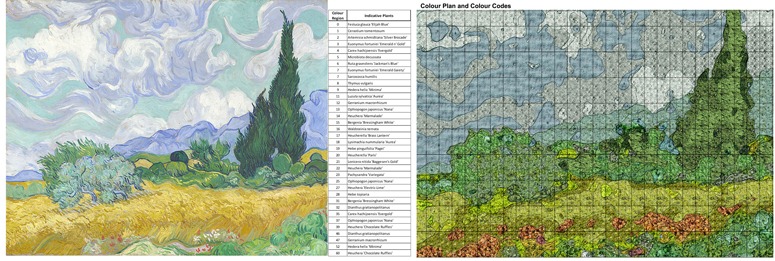

The geographical origins of landscape architecture in Scotland

More geography graduates should think about postgraduate courses in landscape architecture and careers in

landscape architecture, especially if they are from Scotland’s Central Belt. About 500m years ago, in the Silurian period, England and Scotland belonged to different tectonic plates. They were mostly underwater and separated by the Iapetus Ocean. In the Devonian period the plates collided on the line of the Forth Estuary, shown on the photograph. There was much volcanic activity in the region during the Carboniferous period and a volcano formed the Bass Rock, also shown in the above photograph. When the Romans brought an urban civilization to Britain it did not extend north of the Forth and the culture of Highland Scotland remained tribal until the eighteenth century – at which time Edinburgh, some 30km west of the Bass Rock, was one of the most important intellectual centres in Europe. The geography of the landscape Central Scotland is very interesting – and I

wonder if this contributed to the region having given birth to many of the the most important landscape analysts, landscape architects and landscape planners of modern times.

James Hutton lived 15 km south of the Bass Rock and used the geology of the region to support his

Theory of the Earth, which argued that the Earth had evolved slowly, rather than being created in a week (as described in the Bible).

Gilbert Laing Meason invented the term ‘landscape architecture’, in 1828. Meason lived near Forfar (60 km north of the Bass Rock) which might be visible on the above photograph if it had been taken on a clearer day

John Claudius Loudon was the most prolific writer on gardens and architecture of his age. He designed some of the first public parks, proposed a system of

Breathing Zones for London and transmitted the term ‘landscape architecture’ to Downing and Olmsted . Loudon spent his childhood at Gogar 40 km west of the Bass Rock

John Muir is regarded as the Father of America’s National Parks. John Muir was born in Dunbar (15 km from the Bass Rock) and the estuary in the foreground of the above photograph is now the John Muir Country Park.

Patrick Geddes, the first European to use ‘landscape architect’ as a professional title was the most innovative town and country planner of the twentieth century. Patrick Geddes was born near Perth (25 km north of the Bass Rock) and lived in Dundee and Edinburgh

Ian McHarg wrote the most influential landscape architecture book of the twentieth century (

Design with nature) and contributed to the development of Geographical Information Systems (GIS) McHarg was born in Clydebank, 80 km west of the Bass Rock and near the boundary between the tectonic plates which were joined to make Britain

George Eliot wrote, in Adam Bede, that ‘a gardener is Scotch, as a French teacher is Parisian‘. She lived 1819–1880 and would have been on even stronger ground if writing about landscape architecture and planning!

The Bass Rock (centre of photo) is one of many extinct volcanoes which form the landscape architecture of Scotland's Central Belt

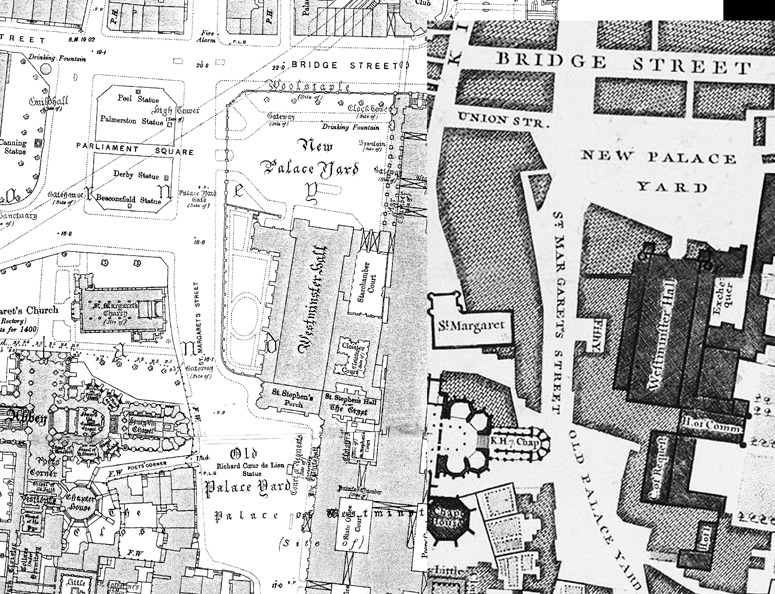

See map history of How Britain was Formed. When the sun is setting (above) one gets a glimpse of how the region looked when the boundary between the Gondwana and Euramerica plates was full of volcanic activity, as Iceland is today, but the Devonian climate was hotter and drier.