This video review of the QE Olympic 2012 Park, by Robert Holden and Tom Turner, comprises a discussion on 29th June and video footage taken on 29th and 30th June. Mainly a review of the master planning, the two landscape architects spent too little time on the park’s often-very-good detailed design. Our fundamental point is that ‘the landscape planning is much better than the landscape design’. The landscape planning includes the opening up of the River Lea in the northern section of the park, the habitat-creation strategy and the park’s excellent links with its hinterland. The landscape design is dominated by vast pedestrian concourses which will be busy during events but will resemble unused airport runways on every other occasion. There is some good garden-type planting but it has not been used to make ‘gardens’: it is used more like strips of planting beside highways.

The designers were EDAW/Aecom, LDA Design with George Hargreaves.

Comments welcome.

Category Archives: landscape planning

The landscape of housing: Smithsons design and site planning for Robin Hood Gardens

Zaha Hadid: ‘Personally, Robin Hood Gardens is one of my favourite projects.’

Richard Rogers: ‘It has heroic scale with beautiful human proportions and has a magical quality. It practically hugs the ground, yet it has also a majestic sense of scale, reminiscent of a Nash terrace.’

Simon Smithson: ‘I believe Robin Hood Gardens to be the most significant building completed by my parents. ‘

Tom Turner: ‘Sao Paolo could learn a lot from the Smithsons’ approach to planning urban landscape’

Here are 3 videos, by Alison and Peter Smithson, by Jonathan Glancey and by me. I am impressed by the Smithsons and in full agreement with Glancey that (1) I would not choose to live there (2) the scheme should not be demolished – as has been decided (3) it should become student housing, because it is so well suited to communal use. The Smithsons account of the scheme justifies slapping a preservation order on Robin Hood Gardens. The English Heritage commissioners were right about the building architecture being mediocre: the elevations are elegant but the roofs are leaking, the concrete is spalling so that the rebars are exposed, the stairways are pokey, the balconies are usable only for drying clothes (so the residents protect them with bird netting) and a ‘street in the air’ (often with hoodies) is not a nice thing to have outside your living room window. BUT the site planning is excellent. London’s ‘tower blocks’ are usually planned like tombstones in plots of grass. The Smithsons protected against noise and used their buildings, as in London’s Georgian Squares, to define and create outdoor space. I have never seen their hill well used but attribute this to its not being a safe protected space. I also agree with their comment, on the video, that using Robin Hood Gardens as a ‘sink estate’ was not wise. Both these mistakes can be attributed to the housing managers: Tower Hamlets Borough Council. So what should be done now? (1) keep the Smithsons excellent site planning (2) implement Glancey’s idea if it feasible – and convert the buildings for use by a student community (3) otherwise, replace their shoddy architecture with better buildings on the same footprint (4) manage the central space as a garden, instead of as a public park.

Alison Smithson has a strange manner and makes some strange remarks (eg ‘Any African state would have as good a chance of joining the Common Market as London’). But the two of them speak wisely about what should happen to London Docklands.

Jonathan Glancey presents a well-reasoned and well-balanced account of the design.

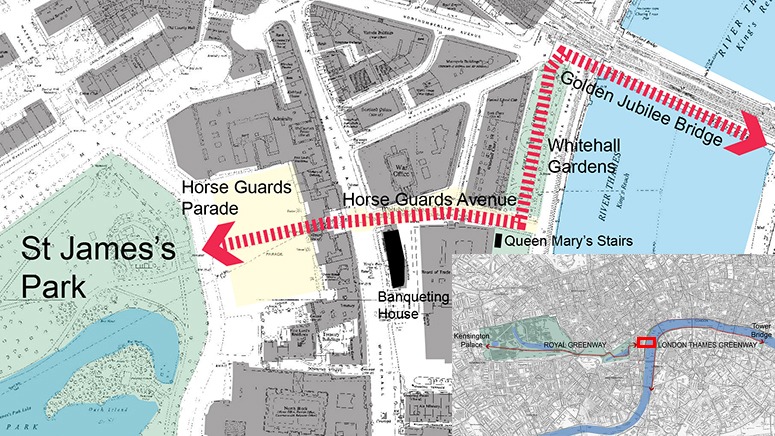

London's Royal Parks Greenway should have the Lost Garden of Whitehall as a link to the South Bank's Thames Greenway

London has two excellent greenways: one of them was planned by Henry VIII and runs through the Royal Parks. The other was planned by a landscape architect (Sir Patrick Abercrombie) and runs on the South Bank of the River Thames from Westminster Bridge to Tower Bridge. The video explains the histories of the routes and how the Lost Garden of Whitehall Palace could and should be a link between the two greenways.

London’s geography is confusing for the pedestrian and the cyclist. A 6-mile London Greenway, running from Kensington Palace to Tower Bridge would create a great east-west spatial corridor, ‘green’ in the sense of environmentally wonderful and a ‘way’ in the sense of a traffic-free pedestrian concourse passing near many of London’s best tourist attractions: the Tower of London, the Globe Theatre, Tate Britain, St Paul’s Cathedral, the London Eye, Westminster Abbey, the Houses of Parliament, the Lost Garden of Whitehall Palace, St James’s Park, Buckingham Palace, Hyde Park, Kensington Palace and Gardens.

The Ministry of Defense (the building on the right in the photograph below) occupies the site of the main buildings of Henry VIII’s Whitehall Palace. The architect preserved a fragment of Queen Mary’s Stairs and the Ministry kindly allow public access to what was Queen Mary’s Garden. We could admire them even more if the parterre’s shown on Knyff’s drawing of the garden were to be restored. Sadly but understandably, the Ministry keeps Henry VIII’s Whitehall Palace Wine Cellar for private use.

Will Ebbsfleet be a Garden City a New Town or an overblown Housing Estate?

1) will it, like the real Garden Cities (Welwyn, Letchworth etc) be an idealistic private enterprise project with an emphasis on gardens, parks and landscape development? No.

2) will it, like the post-1946 New Towns, be a central government project, making money by buying land at agricultural prices and selling some of it at development land prices? We have not been told – but I doubt it.

3) will it be a subsidised housing project with few objectives except ‘get ’em up in time for the next election’? Quite likely.

Now let’s consider the design aspects:

1) will it be a ‘city’ of houses with generous gardens and parks? I doubt it.

2) will it, like most contemporary residential projects in and around London, be a development of medium-rise residential blocks with no ground-level gardens, no green living walls and no roof gardens? Very probably.

So what should be done? I have no objection to using a development corporation to take the project out of local government control (until it is built) PROVIDING central government involvement is used to achieve public interest objectives. They should use development corporation powers to streamline and enhance the planning process. Then they should spend much of the promised £200m on green infrastructure. This would kick-start the project, as is desired, and achieve public goods comparable to those provided by the Garden Cities and the New Towns.

It is significant that the population of Ebbsfleet ‘Garden City’, at 15,000, will be the same as that of England’s best twentieth century housing development: Hampstead Garden Suburb. The Suburb (which is what Ebbsfleet should be called) was designed ‘on garden city lines’ using the transition concept developed on the great estates of the eighteenth and nineteen centuries.

London can become a Roof Garden City – but it needs imaginative design as well as town planning

Ebenezer Howard proposed garden cities outside London. That’s fine but Central London should adopt the landscape policy of becoming a Roof Garden City. Property developers should be rewarded for providing green roof gardens and punished on those few occasions when they find reasons for not providing roof gardens and sustainable green roofs on new buildings. Visually, this is the single most important policy for making London a Green Roof City. As everyone knows, London is already the world’s Garden Capital. Now it should become the world’s Roof Garden Capital.

But I doubt if it will. British town planners are far too unimaginative – and Singapore’s planners are way out in front. As I ride my bike around London I often think ‘Why does the RTPI exist? What, in heaven’s name, do town planners DO? Why not dissolve the Royal Town Planning Institute?’ The answer, I think, is that most of their effort goes into a sometimes-useful attempt to stop landowners doing what they want to do. UK planners seem to have no positive achievements – except, perhaps, in helping developers evade planning restrictions dreamed up by their professional colleagues.

Thomas Mawson published an attractive book on Civic Art in 1911 and became a founder member of what is now the Royal Town Planning Institute in 1914. Then, in 1929, he became first president of what is now the Landscape Institute. Perhaps we need an agreed division of labour between the two professional institutes: the RTPI can stop developers from doing bad things and the Landscape Institute can encourage them to do good things.

Roof SkyPark garden-landscape on Marina Bay Sands Hotel in Singapore

Having proposed a Sky Park for the City of London, I was delighted to see a real Skypark on the Marina Bay Sands Hotel. ‘London talks and Singapore acts’. The Marina Bay Sands Hotel has 2,561 rooms and 55 floors. The SkyPark, 200m above ground level, is larger than three football pitches and has an observation deck, 250 trees and a 150m infinity swimming pool. It is a brilliant project by Las Vegas Sands and, I hope, a signpost to the future of urban form. See the Marina Bay Sands website for more details. I’d like to spend a few nights there, congratulating the hotel management for commissioning the project and then the city of Singpore for its policy of moving from ‘Garden City to Model Green City‘. But a design critic must also provide criticism:

- the garden/landscape design looks ‘OK but dull’. The designers have not risen to the challenge of such a fabulous opportunity, perhaps to re-create some of the rain forest of pre-colonial Singapore with stylised beaches running to the perimeter pool. I wouldn’t even object to a glowing Tarzan by Jeff Koons in the heart of the jungle – and nor would the kids of the guests.

- As built, SkyPark floats somewhere between the deck of a luxury cruise ship and the garden of a luxury hotel – and both are design categories which landscape designers neglect. What the SkyPark needed was a serious dreamland design to lift the imagination of guests, as well as the contents of their wallets. Moshe Safdie was the architect. He worked with five artists but, having written a book For everyone a garden probably sees himself as an expert on garden design. I do not doubt that, like Frank Lloyd Wright, Safdie has the ability to design gardens but as with all the arts, it takes time to develop expertise and one needs to love garden life and garden visiting to succeed. My belief is that Edwin Lutyens’ best gardens were designed in co-operation with Gertrude Jekyll and that Lutyens tended towards vacant formalism when working, like Safdie, on his own. Eero Saarinen had the great good sense to work with Dan Kiley.

- the Tropical Island shape of the SkyPark sits unhappily on its three towers. There is a dash of HG Wells’ War of the Worlds about it. Or an out-or-water oil rig. Looking up, one wonders if a Tsunami left a cruiseliner or a surfboard perched on the roofs of its three towers. The resort hotel may appear more sensitive to its context when more of Singapore’s buildings have SkyParks

- Safdie’s urban design, which I commend but which is not apparent from the photographs, was as follows: ‘A series of layered gardens provide ample green space throughout Marina Bay Sands, extending the tropical garden landscape from Marina City Park towards the Bayfront. The landscape network reinforces urban connections with the resort’s surroundings and every level of the district has green space that is accessible to the public. Generous pedestrian streets open to tropical plantings and water views. Half of the roofs of the hotel, convention center, shopping mall, and casino complex are planted with trees and gardens.

Top photographs courtesy Marina Bay Sands Hotel. Bottom photo courtesy Peter Morgan.