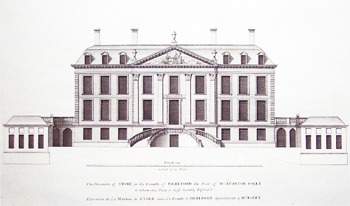

This tapestry (dated 1710-20) was rescued from a fire at Stoke Edith Park in 1927 (see aerial photo of Stoke Edith today). It shows a garden which may have belonged to Stoke Edith House and which may have been designed by George London. It is the principal section of a compartment garden, designed for walking and for displaying the owners valuable statues and valuable flowers. The planted ribbons (plate-bandes) and the nature of their planting are clearly shown, as are the citrus fruits in tubs, placed outside for the summer to scent the air and provide fresh fruits which were otherwise unobtainable. The building at the far end of the parterre is an orangery.The design style is that of the Late Renaissance.

The use and the layout remind one of the squares of eighteenth century London and Paris (eg the Place des Vosges) – which were, in effect communal parterres. I see the urban examples as landscape urbanism in the sense of city plans inspired by garden and landscape plans.

When the Stoke Edith parterre was made the surrounding settlements (eg Hereford) were, presumably, densely packed and grubby almost-medieval towns. Their ‘shared space’ would have been roads for riding: unpaved and strewn with animal dung. For fine ladies in fine clothes they were not suitable places to take the air – so they needed gardens with gravel walks, statues and flowers to admire. The social use of the garden space is evident.

A Stoke Edith gate lodge (built in 1792) survives on a bend in the road between Ledbury and Hereford.

Images courtesy Wikipedia. See photograph of Stoke Edith garden and parterre before 1927

It is very interesting to think landscape urbanism in relation to garden design.This picture illustrates that the city “developed” from a garden idea. But with regard to landscape urbanism as a theory for future landscape planning and design, what do you think it will have on urban planning? Are you suggesting that cities should be built on similar theories to those used to build gardens? What can we “learn from garden design” which is relevant to urban design?

Yuan, I have tried to answer your question with another post on garden design and landscape urbanism – partly because I am inordinately fond of the photograph of the Forth Bridge Design Model. Gardens make excellent models and they are closely bound into ecosystems. So are cities but the scale is so large that it is difficult to comprehend the relationships.

Views (to distant vistas) and axeses (which establish connecting and organising relationships) are two of the primary lessons learnt from garden design which have been translated to urban planning and design.

Views and axes are certainly two of the easiest lessons to learn but they are far from being the only lessons. But one could also widen this out and say that the design of garden+house is a unitary design project so that what we are talking about is ‘what can be learned at the domestic scale and applied at the urban scale’. One of the lessons, surely, is that the design of indoor space should normally be integrated with the design of outdoor space. The great mistake of the modern era was to ‘abstract’ one from the other – and I hope this blog is helping, by an iota, to bring them back together.

This is certainly true. I suppose the best examples to look for are where the house and garden have consciously been designed as a unitary project.

The following advice about a borrowed view is courtesy of the Australian Plant Society (Victoria):

“If you are close to natural bushland the opportunity to make use of the “borrowed landscape” should influence your design and with due care enable you to make use of what you can see, like tree canopy beyond your own property, to enlarge your sense of space. If you incorporate some of the neighboring bushland plants into the design of your garden you should also be able to make a seamless transition from bush to home garden, preserving a “sense of place”.”

The theory of borrowed landscape has its genesis in the Picturesque. In East Asian garden design I believe a similar principle is called ‘shakkei’. There seems to be considerable debate around the role of Sir William Temple in promoting ‘the beauty of studied irregularity’ (said to derive from Chinese landscape design) and its influence on the development of the Picturesque.

I like the advice from the Australian Plant Society but its grasp of design history is muddled.

By the way,the first book on landscape architecture was about the study of building design in relation to natural landscape – it was only marginally about the design and use of outdoor space. See note on the origin of landscape architecture.

The theoretical muddle is entirely mine, so please feel free to straighten it out.

Some say William Gilpin introduced the picturesque into the English cultural debate with his text ‘Observations on the River Wye, and Several Parts of South Wales, etc relative chiefly to Picturesque Beauty; made in the Summer of the year 1770’.

William Temple’s (the statesman and essayist) influence however was in promoting the Chinese landscape principle of borrowed scenery was through his essay ‘Upon the Gardens of Epicurus; or Of Gardening in the year 1685.’ Edmund Burke was said to have followed Temple’s ideas of ‘Sarawadgi’ garden design (the beauty of studied irregularity) in ‘A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful.’

Of course the developmental leap from the theories and origins of the picturesque to the advice of the Australian Plant Society to the residential sector is a quantum one: something akin to the influence of architecture on building.

Sorry. It’s not so much a muddle as the point that the Picturesque is western idea (which probably does originate with William Gilpin) and shakkei is an eastern idea, from Japan (and possibly, before that, from China). Sharawadgi may also be a Japanese idea. There is surely a similarity between the western and eastern approaches to the incoroporation of scenery in garden design, but this does not entail an ideological relationship.

I like your wry comment about ‘the influence of architecture on building’. But if one accepts them as different things, it complicates the question of ‘What is architecture?’. We always have this with ‘What is landscape architecture’ but architecture has much more ontological security.