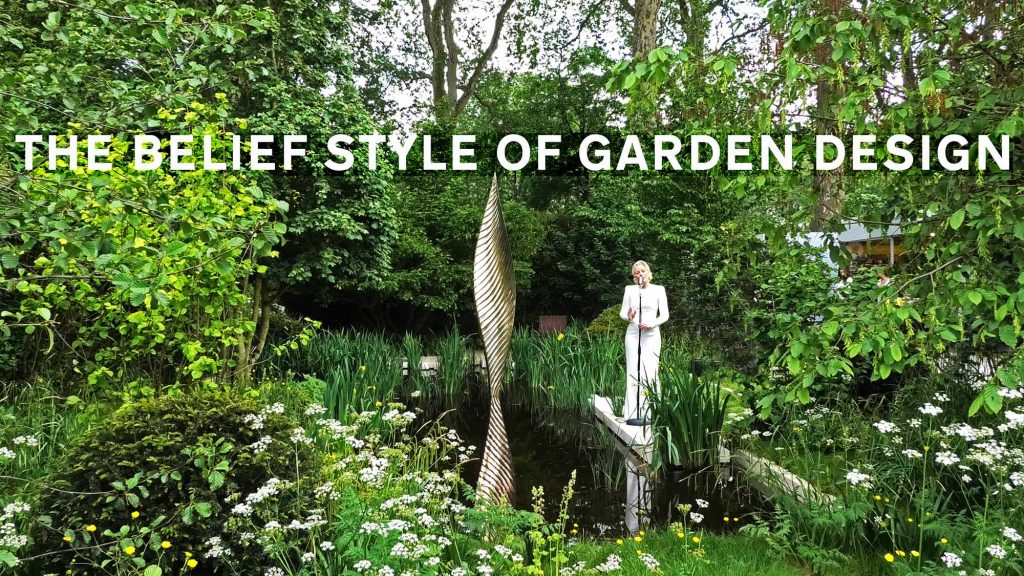

The Belief Style of garden design was prominent at the 2019 Chelsea Flower Show. This example, The Savills and David Harber Garden, was designed by Andrew Duff

While admiring the 2019 Chelsea Flower Show, I thought of a name for an emerging style of garden design. The primary characteristic of the Belief Style is a new view of Nature: as simultaneously endangered, life-enhancing and in need of conservation by and for humanity. Perhaps it will earn a place on the Gardenvisit chart of Historic Styles of Garden Design.

Though I have used ‘belief’ in the titles of books about garden history, I have not used it to characterise a specific design approach. My reason for doing so now is to clarify and enhance an important trend in both garden design and landscape architecture. Without accurate terminology, the development of concepts is hindered.

The dominant design trends of the twentieth century were Modernist and Postmodernist. Both influenced gardens. But both advance on the path to obsolescence every time the clock ticks. With an inward smile, I used the term post-Postmodern in the sub-title of a book on design theory: City as landscape: a post-Postmodern view of design and planning. It’s cumbersome and when I checked the order of ‘design’ and ‘planning’ this morning I noticed that Amazon had contracted it to post-Modern. ‘Belief’ may also be a substitute for ‘post-Postmodern’ in other contexts. Time will tell.

With regard to art and design, the names I prefer to Modern and Postmodern are Abstract and Post-Abstract. They tell us ‘what’s in the box’ rather than ‘when the box was opened’.

The word ‘belief’ does not mean the same as either ‘religion’ or ‘faith’. Not everybody has a religion. But we all have beliefs in the sense of things we hold to be true that cannot be established by rational empirical science. Even such determined anti-theists as Christopher Hitchens, Richard Dawkin and Stephen Fry have beliefs. I assume, for example, they have beliefs in the wickedness of cruelty and the virtues of kindness. Both could could influence garden design.

In these agnostic times the belief that is most foregrounded (to use a term favoured by postmodernists) is in the overwhelming importance of nature. This is not new. But it is now being linked with beliefs about conservation, sustainability, climate change, biodiversity, physical health and mental health.

The garden awarded the 2019 RHS Chelsea Best in Show Medal is a good example, designed by Andy Sturgeon.

We also see a love of nature in the work of William Robinson (mentioned by Sarah Eberle). But though he talked about a wild garden he is not in fact believed to have made a dominant use of wild plants in his own garden. Alfred Parson‘s illustrations to his books are another matter and have a real commonality with some of the planting design at Chelsea.most important these planting designs are favoured both by the RHS and by the Chelsea judges.

What designers say about their work is almost as significant as what they do. Here are some examples, not coordinated with the video clips.

Andy Sturgeon, who won the Best in Show award for the M&G garden, uses ‘a biodiverse range of pioneering plant species from around the world’ to demonstrate ‘nature’s power to regenerate’.

The RHS ‘Back to Nature Garden-, designed by the Duchess of Cambridge with landscape architects Davies White, is conceived ‘as a place to retreat from the world’ while promoting ‘physical and emotional wellbeing’.

Andrew Duff, explaining his design for ‘The Savills and David Harber Garden’, states that ‘The most important aspect of this garden is its underlying sustainability’.

Sarah Eberle, in a design for the Forestry Commission, explores how gardens and landscapes ‘can be made resilient to the threats posed by a changing climate, pests and diseases’.

Beliefs always have been a fundamental aspect of garden design so I’m happy that new beliefs are leading to a new design style – which I hope you can appreciate from the video clips we’ve been looking at. They focus on planting design and are not classified by designer, but the potential scope of the style is much wider – and merits another blog post.

The Belief Style of garden design is related to William Robinson’s Wild Garden but also strikes off in a new direction