The Cultural Landscape Association (CLA) is a non-profit organization specialized in the area of Cultural Landscape and the only institution in Iran that focuses on cultural landscapes interdisciplinary. The Association’s mission is to strengthen the role of cultural landscape in sustainable development in Iran and the Middle East region, by building the capacity of all those professionals and bodies involved with cultural landscape recognition, protection, conservation and management in the region, through training, research, the dissemination of information and network building.

The members of the association are academicians, experts, and ex. managers from different disciplines who work on research projects with the collaboration of internal and external institutions. In addition to research projects, CLA also holds conferences, meetings, and specialized tours.

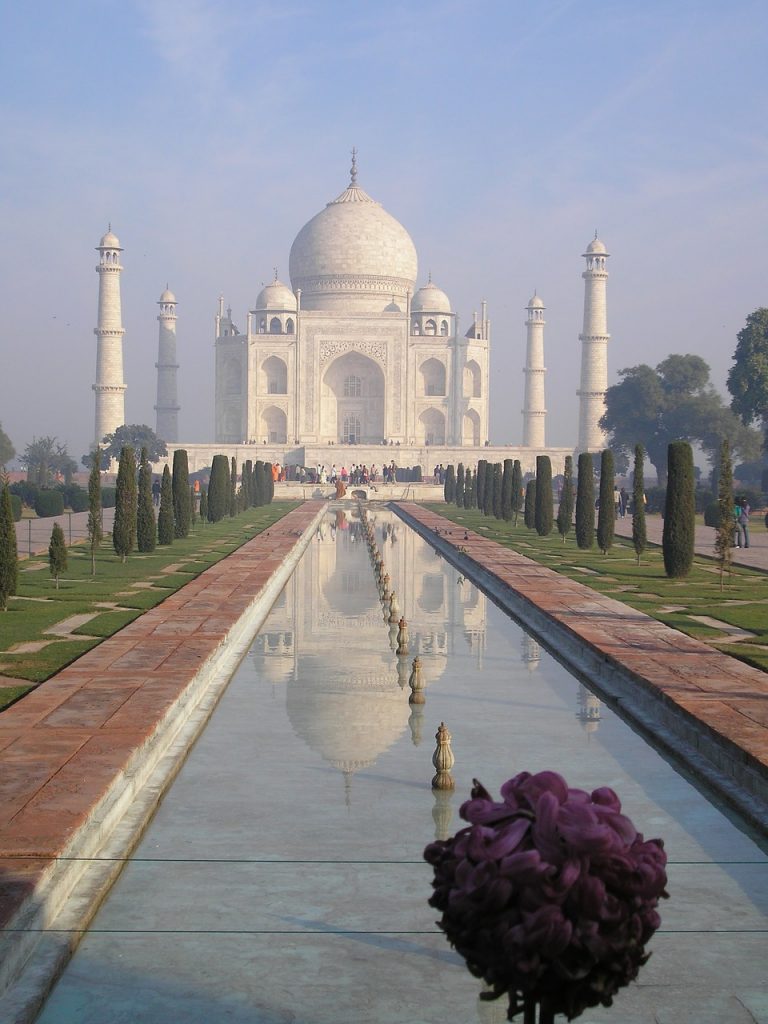

Now, after our very successful international tours and on-site workshops “Taste Paradise” in May 2013, “Landscape Transformation” in May 2015, and “Taste Persian Cultural Landscape & Architecture” in November 2018, The Cultural Landscape Association (CLA) is planning to orchestrate another on-site workshop and journey (Taste Paradise II) for experts and professionals all around the globe, to visit and enjoy the cultural beauty of Persian Gardens on 27 Apr.-04 May 2019. It is a good opportunity for whom want to taste Iranian culture and history. In order to raise its quality, these workshops are only available to a limited number of people (20 participants for each tour) at the time, so it would be better if applicants register earlier not to lose the chance.

For more information, please see the tour webpage: http://classociation.org/upcoming/ or contact :info@classociation.org or classociation1@gmail.com

Mohammad Motallebi

Interim President – IFLA Middle East

CEO city & Landscape Group