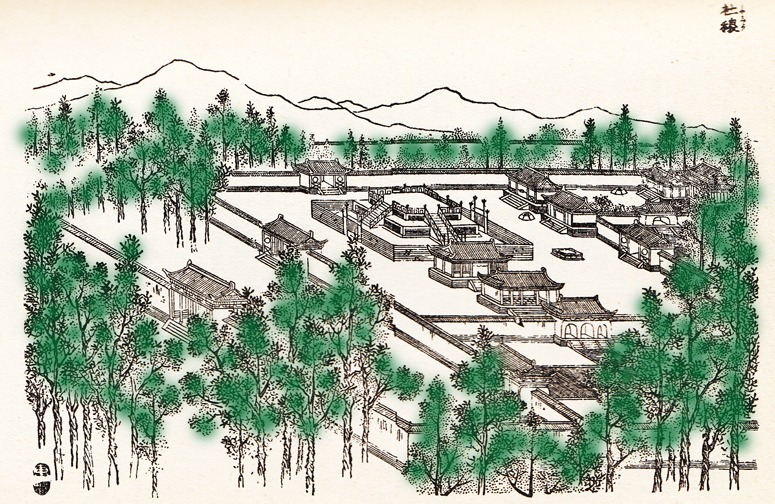

Without knowing too much about Masdar City, I am sceptical about Norman Foster’s proposals. So my suggestion is to develop a Masdar City Two with its focus on using a happy blend of traditional technology with as-little-as-necessary high technology. I would have David MacKay as the energy supremo and Hasan Fathy (had he not died in 1989) as the chief architect – and a landscape planner responsibile for the strategic direction of the new city. I guess there would be lots of mud walls, planting, and shade with excellent provision for cycling and electric floats for transport (as in Nanjing Street, Shanghai). All the roof space would be roof gardens with retractable awnings and limited vegetation supported by grey water. The gardens would be legendary – and related to the lost gardens of Ancient Mesopotamia. I think the result would be cheaper, better, more sustainable and more popular than Masdar City One. It might get less coverage in the architectural press but we could live with this.

Sorry about the quality of the above photograph, taken in 1975. I went to re-take the photo 30 years later and could not find the place – I guess it has been destroyed. The residents of Old Gourna (or Kurna or Qurna) did not want to leave their homes amongst the tombs of the nobles, which had rich pickings and many tourists. Fathy was unpopular in Egypt but designed some beautiful and environmentally appropriate homes for Saudi princes.

Odd that Iran should want nuclear power and Abu Dhabi should want solar power. What next? Will Iceland start making artificial snow? Or is Masdar City One really, as I will assume, an enlightened example of a rich country using its resources to develop technology which will benefit the world? The competition between Masdar City One and Masdar City Two would be very healthy and there should be a prize for the winning design team. Success would be judged from three criteria (1) construction costs (2) measures of sustainability (3) popularity with residents.