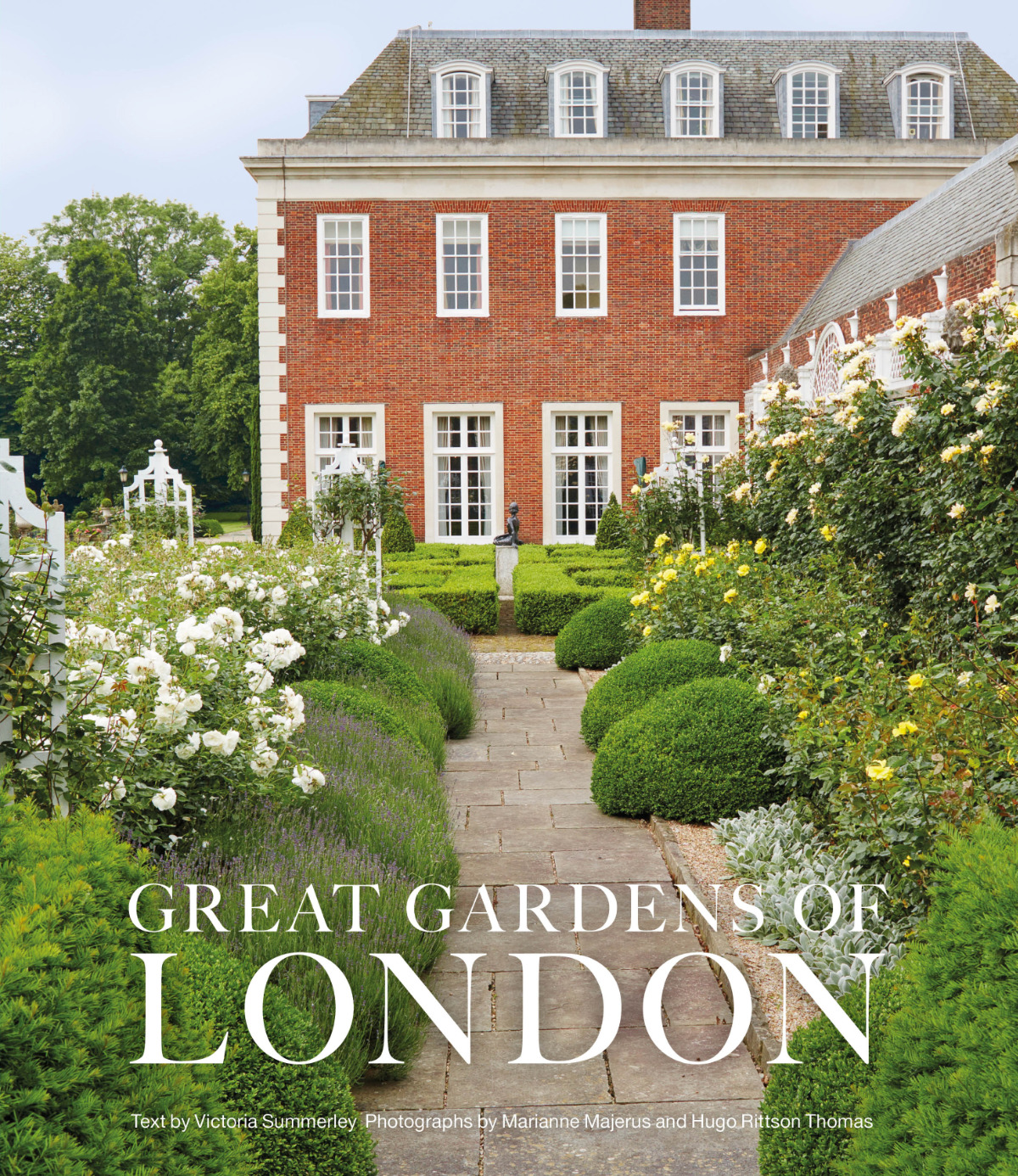

Good writing and good photography are real assets for garden books. Great Gardens of London was produced by a skilled investigative journalist working with two expert photographers. Victoria Summerley explains that the book is ‘aimed at residents and visitors alike’. Yes. But it is not particularly aimed at garden visitors. Or should I say ‘it is not aimea at all garden visitors’. The book’s first garden is that of the Prime Minister’s official London residence: 10 Downing Street. Doubtless it has been seen by many important visitors to London but I doubt if many travellers on omnibuses from Clapham are to be counted among their number.

Frances Lincoln (2015) ISBN-10: 0711236119, ISBN-13: 978-0711236110

Frances Lincoln (2015) ISBN-10: 0711236119, ISBN-13: 978-0711236110

The book has a map and appendix with details of which gardens can be visited: 13 of the gardens are never open and 17 are open in various degrees. I did not know that Downing Street lets in a few visitors by ballot. Another appendix suggests more gardens to visit.

America is said to have less of a class system but Winfield House, second in the book and the American ambassador’s London residence, is not part of the tourist circuit. No matter: the book is a great opportunity to see and read about these important gardens.

I don’t know whether to be pleased or sorry that PM Gordon Brown’s wife (Sarah) introduced raised vegetable beds to Downing Street. Good to think of the happy couple doing something useful with their time but I worry about how the beds fit into the garden aesthetically and about why they wanted the beds to be raised. Did they use railway sleepers? Raised beds are fashionable, and possibly a Tory idea, but my experience is that unless your ground is badly drained or polluted, or you want to avoid carrot fly, vegetables do better in unraised beds and need less watering. I’d like to know whether Downing Street harvests rainwater for its garden – or does it make unsustainable use of tap water? I was interested to read that Margaret Thatcher commissioned the Downing Street rose beds and that they contain a rose named after her. Great that it survived the dark age of Blair and Brown, much as the nearby statue of Charles I survived the Civil War. Do they use strips of iron to protect the adjoining lawn?

Sustainable gardening is high on the agenda for Winfield House. Even memos are composted. Just think how much Wikileaks trouble would have been avoided if the US had stuck to composting. Obama liked Winfield garden so much that he joked about wishing he had been Ambassador to London instead of President.

The gardens and parks in the book which are accessible to the public are well worth visiting, though most are flattered by the excellence of the photography. Eltham Palace Garden is an interesting place but, despite continued efforts by English Heritage, I find the quality of the gardens disappointing. Summerly sees Eltham as the product of ‘two dynasties’: the Tudors and the Courtaulds. But one does not sense their tastes in the design. It looks like a municipal park. English Heritage say the aim is restore Eltham to the style of the 1930s and they have used archive material to this end. Perhaps the problem is that the Art Deco style, which worked well for rebuilding Eltham Palace, was never resolved in English gardens. Fletcher Steele, as he showed at Naumkeag, could have done a much better job.

The garden of Horace Walpole’s Strawberry Hill was ‘pretty dreadful’ before the Strawberry Hill Trust began a £9m restoration of the house and garden in 2009. Generally, I think individuals and trusts do a better job of this kind of work than bodies, like English Heritage, with national responsibilities. The Strawberry Hill Trustees have the wisdom to run a volunteer programme. Why don’t all publicly owned green spaces do this?

The next chapter is on Hampton Court, where much garden history research and restoration has been carried out. I am sorry that the book does not use historical drawings or plans but can understand that they might be thought unsuitable for a non-specialist readership.

Moving on, I was very pleased to find a chapter on the Downings Road Floating Gardens in Bermondsey. The wretched, unimaginative, blinkered bureaucrats of Southwark Council have been trying to get them removed for years. Their inclusion may help those who have long campaigned for their recognition and protection.

The book’s 30 gardens are categorised into five chapters. Some are unconvincing as groups. Chapter 4, on roof gardens, is a good group and a pleasure to discover. My dream is that London will become a Roof Garden City. This chapter shows what is possible. Most roof gardens are, understandably, not open to the public. But they are great places and, unlike most of the design styles represented in the book, they look contemporary. Jane Brown wrote of ‘the gardens of a golden afternoon’. Much though I like them, that afternoon continues to linger on beyond its natural lifespan. What London needs is a wealth of roof gardens. Unlike many capital cities, including Washington, Delhi, Beijing, Tokyo and Moscow, London has a climate which is very well suited to the enjoyment of roofs – providing they are well planned and well designed. I hope the second edition of Victoria Summerley’s Great Gardens of London will include the University of Greenwich Roof Garden in Stockwell Street. And if space can be found, I’d like to have more discussion of garden design styles.

Tom Turner