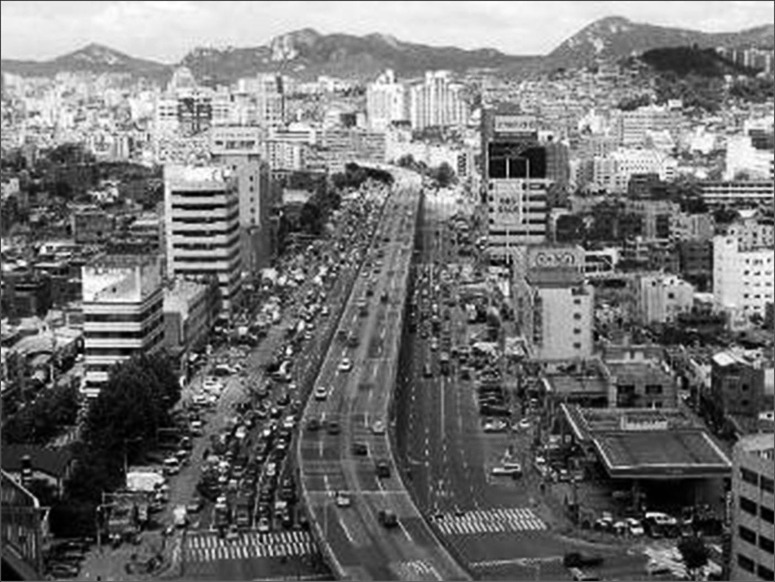

Beijing urban landscape: well-built but bad landscape architecture 北京成功建设,但差强人意的中国风景园林.

China is urbanizing at a faster rate than any other country has ever done and therefore has a greater need for qualified landscape architects than any country has ever had. At present, a Chinese friend informs me, there is a single qualification for Architecture and Urban planning and graduates are divided into two classes. In 2009 the First Class had 18,639 qualified architects and the Second Class had 16,000 urban planners. There are no officially qualified landscape architects in China but there are qualified companies and institutes in which the members can hold qualifications in architecture, urban planning, landscape architecture, environmental design, horticulture, forestry and other subjects.

My view, based on the experience of other countries, is that China will need a professionally recognized landscape architecture profession. This differs from the professions of architecture, urban planning, horticulture, environmental design etc. The fundamental skill is in

the composition of five elements (landform, planting, water, buildings and paving) to create good places. These places, as Ian Thompson argued (in Ecology, Community and Delight: sources of value in landscape architecture) should be ecologically good, visually good and socially good – in combination or in isolation. This is exactly the skill which was used to make the Imperial Parks and Classical Gardens of Ancient China but if students have a limited education they will not be equal to the task. For example (1) architects and urban designers do not know enough about landfom, water and planting (2) horticulturalists and environmental designers do not know enough about aesthetics, or about structures, or about the social use of outdoor space (3) ecologists and geographers do not know enough about landscape art or basic landscape design.

As to the number of landscape architects China needs, or rather needed 25 years ago, one can make a simple estimate based on the number of landscape architects/head of population in Europe:

my estimate is 120,000. But one could argue that if China’s middle class has 80m people then it ‘only’ needs the same number of landscape architects as Germany. Comments welcome – I am not Chinese and do not know the country well.

(Image courtesy P.)

Many thanks to Poppy for this translation into Chinese:

中国具备多少具有从业资格的风景园林师? 中国需要多少这样的风景园林师?

中国的城市化进程超越了任何其他国家,因此对风景园林师的需求也是超越任何其他国家的。一位中国朋友告诉我,目前中国有独立对建筑师,城市规划师的两类资格评估。在2009年,具有资格的建筑师18,639名,具有资格的城市规划师16,000名。在中国还没有对风景园林师的官方认证,而只有在公司和机构中的成员能够取得建筑师,城市规划师,风景园林师,环境设计师,园艺师,其他专业的资质评审。

基于对其他国家的了解,我认为中国需要一个对风景园林从业人员的专业认证。这个认证将有别于建筑设计,城市规划,园艺,环境设计等等。风景园林设计的技能是基于对主要五种要素的组织(地形,种植,水,建筑,道路铺装)以创造出优美的场所。这样的场所,按照伊恩•汤普森所言(风景园林的价值来源于:生态学,社会学和给人带来愉悦),应该是有良好的生态性,良好的美学性和良好的社会性–共同具备或单一具备这样的特点。这是创造中国皇家园林和古典园林的精湛技艺,但是如果学生对此所受教育不够就不能胜任其职。 比如说:(1)建筑师和城市规划师对地形,水体和种植知之甚少。(2)园艺师,环境设计师的美学知识不够,也没有构造学,和户外空间的知识。(3)生态学家和地理学家基本不了解园林艺术和基本的设计常识。

关于中国需要风景园林师的数量,或者说25年前中国需要风景园林师的数量,我们可以估计一下,遵循一个简单的在欧洲的原则: 风景园林师的数量/人口数量。那么我的估计是中国需要120,000名风景园林师。然而,有人也会说如果中国的中产阶级有80,000,000人,那么所需风景园林师的数量就和德国一样。欢迎大家踊跃讨论,因为我不是中国人,对中国了解不没有中国人深刻。