This photo (taken near Waterloo East Station in South London) helps make the point that the ‘urban design theory’ underpinning the misguided design of Barking Town Square dates from the 1960s. It was wrong then and it is wrong now. Muf Architecture’s office is in East London but they could well have been inspired by Waterloo. Note the chain link fencing. Why not plant it with convolvulus? – the Rasta temple in Camberwell could let us regard this as a context-sentsitive approach! Or, better, plant it with runner beans – nice red flowers and then some good organic food to eat.

Category Archives: Landscape Architecture

Public Art in Barking Town Square

Nothwithstanding our criticism of the urban design of Barking Town Square, Muf deserve an award for an excellent piece of public art on the northeast side of the Square. Muf state that ‘The folly screens the flank wall of Iceland supermarket and makes the fourth elevation to the town square. The folly is comprised of architectural salvage and recovers the texture of lost historic fabric of the town centre; it stands as a mementomori to this current cycle of regeneration.’

Unlike the usual ‘Turd in the Plaza’ approach to public art, this wall:

(1) serves an urban design objective by enclosing the space

(2) picks up on the historic context of Barking

(3) pleases the eye without being attention-seeking

I wish we could have more context-sensitive public art.

Barking Town Square does not deserve a public open space award

I’d never been to Barking. But in 2008 Barking Town Square won the the 5th European Prize for Urban Public Space so I went to have a look. Sorry about the weak pun, but the judges are Barking Mad. The main building has a sentimental Bauhaus-ey charm but the urban space is a plain rectangle of pink Spanish granite, laid in stretcher bond for no good reason. The hoardings illustrate some planting to come but the “Public Open Space” is a void, an empty space, a nothing. The judges all represent organizations which promote the art of architecture, which is fair enough, because the building is OK, but this is NOT a good urban square. It is as though Jane Jacobs and William H Whyte had never lived. There is no mixed use: the adjoining buildings are all municipal, without the shops and cafes which might have provided users. There is nowhere to sit, ignoring wisdom of Jan Ghel. The ‘square’ is almost a cul-de-sac, ignoring Ed Bacon and Bill Hillier. The paving is non-SUDS. The only redeeming feature is a piece of public art described as a “7 metre high folly [which] recreates a fragment of the imaginary lost past of Barking”. But why re-create an imaginary lost past? Barking had a medieval abbey. Captain Cook was married in a Barking church. Then there is the cultural context. Barking has one of the largest immigrant communities in London, with many from the Punjab and Sub-Saharan Africa – neither of which region is known to admire the Bauhaus. Some architects show genius in urban design. Muf muffed it.

Note: The photograph was taken at about 11.30 am on an unseasonably warm autumn day (28th September 2008). The good urban spaces in London were overflowing with people. The places which remind one of pre-1989 East Berlin were empty.

Roberto Burle Marx as a context-sensitive designer

As a painter, Roberto Burle Marx was an international abstract expressionist. But as a garden designer and landscape architect he showed a high degree of sensitivity to context – I say ‘surprising’ only because I was so slow to appreciate the complexity of this point. His planting was voluptuously Brazilian, like his mother, and Marx could see no reason for using European plants. Nor did he see any reason for the hard detailing to draw inspiration from the land of his father: Germany. Instead, he drew upon the country whose language is spoken in Brazil. The accompanying photograph is of Copacabana Beach – but could just as well have been taken in Portugal. Until I went to Portugal, I thought this amazing design was an example of Burle Marx inventiveness as an abstract painter. I was very wrong.

Ted Fawcett on Gardens in English and Chinese Poetry

It is a pleasure to discover Ted Fawcett’s love of gardens is undimmed. Writing in the Historic Gardens Review (August 2008 Issue, p.12), he observes that ‘Gardens are the poetry of landscape. They contain, in concentrated form, views, water, trees and flowers and so, like poetry, purvey an essence’. The implication is that landscapes are prose and gardens are poetry. He quotes a beautiful verse from Po Chu-i (AD 772-846) ‘at that time the best-known poet in the world’:

It is a pleasure to discover Ted Fawcett’s love of gardens is undimmed. Writing in the Historic Gardens Review (August 2008 Issue, p.12), he observes that ‘Gardens are the poetry of landscape. They contain, in concentrated form, views, water, trees and flowers and so, like poetry, purvey an essence’. The implication is that landscapes are prose and gardens are poetry. He quotes a beautiful verse from Po Chu-i (AD 772-846) ‘at that time the best-known poet in the world’:

The red flowers hang like a heavy mist;

The white flowers gleam like a fall of snow.

The wandering bees cannot bear to leave them;

The sweet birds come there to roost.

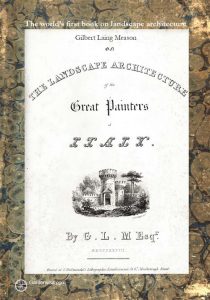

Did Morel, Meason or Olmsted invent the term 'landscape architecture'?

A reader makes the following point: ‘On your site you stated that: “The name “landscape architecture” was invented by a Scotsman in 1828’ but, landscape architecture actually originated in France. There, in the year 1804 Jean-Marie Morel introduced; ‘architecte-paysagiste’ in order to distinguish (his profession) garden architecture from landscape architecture.’ There are in fact 3 candidates for the questionable credit of having invented the term landscape architecture: Morel, Meason and Olmsted.

A reader makes the following point: ‘On your site you stated that: “The name “landscape architecture” was invented by a Scotsman in 1828’ but, landscape architecture actually originated in France. There, in the year 1804 Jean-Marie Morel introduced; ‘architecte-paysagiste’ in order to distinguish (his profession) garden architecture from landscape architecture.’ There are in fact 3 candidates for the questionable credit of having invented the term landscape architecture: Morel, Meason and Olmsted.

Jean-Marie Morel (1728 — 1810) published a book on the Théorie des Jardins (Paris 1776). He had trained as an architect and became an advocate of the ‘natural style of landscape gardening’. He worked for Girardin at Ermenonville and, in 1804, coined the term architecte-paysagiste, for which ‘landscape architect’ is a fair translation.

Gilbert Laing Meason, a Scotsman, wrote the world’s first book using the English term ‘landscape architecture’. It was published in 1828 and Meason had little interest in gardens. His inspiration came from the great landscape paintings of Italy and the writings of Vitruvius. In combining the nouns landscape and architecture, his concern was for what architects could learn from landscape paintings. The difference between Meason’s and Morel’s terms equates to that between a fish box and a box of fish. Buildings contribute to containing space; landscapes are the spaces contained by buildings, landform and vegetation. It is a fundamental distinction.

Frederick Law Olmsted was the first man to use ‘landscape architect’ as a professional title and one cannot doubt that he learned of the term from his partner, Calvert Vaux, who learned of it from Andrew Jackson Downing, who learned of it from Loudon who learned of it from Meason. I therefore regard Meason as the man who invented the term ‘landscape architecture’ and, despite other respectable claims, Alexander Graham Bell as the man who intented the telephone.

It is regrettable that Olmsted did not, so far as I know, read either Meason or Vitruvius. They could have provided a firmer theoretical base for the new profession than Downing or Vaux. John Dixon Hunt comments that ‘there was never a body of specialists to compose treatises specifically for what we have come to call landscape architecture, as Vitruvius did for architecture’. But if, like me, you take Meason as the inventor of landscape architecture then the necessary base can be uncovered by pushing aside a few leaves. To help with this task, we have published the most relevant chapter from Meason as an eBook. Please see: http://www.gardenvisit.com/ebooks