I wish Iran would devote less effort to enriching uranium and more to enriching Iranian gardens and conserving Persian gardens. Persia was one of the central powers in garden history, drawing upon and influencing Mesopotamia, Central Asia, India and Islam. My own modest proposal for conserving the Bagh-e Fin will be the subject of a future blog post.

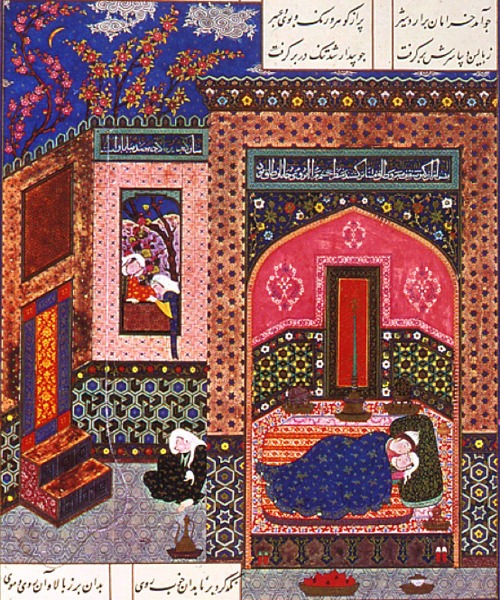

Omar Khayyám (1048-1131), born in Nishapur, was an astronomer and a garden poet. The Rubiayat of Omar Khayyam, 1120 CE, begins:

I

Wake! For the Sun behind yon Eastern height

Has chased the Session of the Stars from Night;

And to the field of Heav’n ascending, strikes

The Sultan’s Turret with a Shaft of Light.

Awake Morning: For the sun behind yon eastern height.]

II

Before the phantom of False morning died,

Methought a Voice within the Tavern cried,

“When all the Temple is prepared within,

Why lags the drowsy Worshipper outside?”

III

And, as the Cock crew, those who stood before

The Tavern shouted – “Open then the Door!

You know how little while we have to stay,

And, once departed, may return no more.”

IV

Now the New Year reviving old Desires,

The thoughtful Soul to Solitude retires,

Where the White Hand of Moses on the Bough

Puts out, and Jesus from the Ground suspires.

V

Iram indeed is gone with all his Rose,

And Jamshyd’s Sev’n – ring’d Cup where no one knows;

But still a Ruby gushes from the Vine,

And many a Garden by the Water blows.