After years of deliberation, they have begun pulling down the Ferrier Estate in Kidbrooke (London Borough of Greenwich). The estate looks decent, many of the external spaces are good and many of the residents were very happy living there. SO WHAT WENT WRONG?

After years of deliberation, they have begun pulling down the Ferrier Estate in Kidbrooke (London Borough of Greenwich). The estate looks decent, many of the external spaces are good and many of the residents were very happy living there. SO WHAT WENT WRONG?

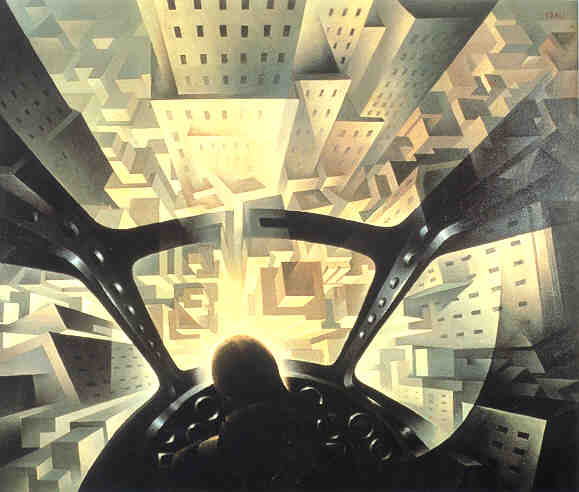

See what the Ferrier Residents Action Group thinks. The London Evening Standard summarizes the situation as follows: “The Ferrier Estate is seen as one of London’s worst examples of Seventies planning, and its concrete towers were allowed to run down over three decades. Unemployment among its residents has been as high as 75 per cent. The estate was also plagued by crime and violence.” But unemployment, crime and violence (and drug-dealing) are not design problems and, as the Evening Standard‘s illustration shows, the morphology of the new housing is uncannily similar to the housing one can see being demolished (on the left side of the photograph).

I remember working on a number of projects like the Ferrier Estate during the 1970s and on one occasion the project team wanted to reduce the external works budget. I told them that ‘The oak trees on my drawings will be approaching maturity when they come to demolish your trashy little boxes’. On the evidence of the Ferrier Estate I might have added that ‘if you give me some money to spend on garden walls it might evey prolong their life’ (let’s hope they keep the good courtyards on the Ferrier Estate). If more musical, I should then have sung Pete Seeger’s Little Boxes:

Little boxes on the hillside

Little boxes made of ticky tacky

Little boxes

Little boxes

Little boxes all the same

There’s a green one and a pink one

And a blue one and a yellow one

And they’re all made out of ticky tacky

And they all look just the same Listen to Pete Seeger

The nicely treed courtyard in the photograph should have been (1) overlooked from the surrounding flats, as a traditional London Square would be (2) accessible to residents only (like the London squares around Ladbroke Grove). As presently managed, it should not be called a ‘yard’ or ‘garden’ – it is merely a public open space (POS) with no evident use. Bad management by Greenwich Council should not be used as an excuse for destroying the space.