The illustrations are excellent but the text is disappointing. Italian gardens suggests a book about the gardens of Italy but as the subtitle – a cultural history reveals it is not a book about garden design. Design is mentioned but it is not treated systematically. Chapter 2, on Medici gardeners 1518-1550 opens as follows ‘The desire to make gardens is like a hereditary disease’. While not objecting to wit, I do not see this as a useful explanation of how one of history’s greatest gardening families acquired its passion for gardens. Nor does Atlee give any account of Italy’s Roman gardens, as the title would lead one to expect. A newcomer to the subject might think the first gardens ever made in Italy date from the fourteenth century. Atlee is the author of several travel guides to Italian gardens and this book is more akin to a guide book than a history book.

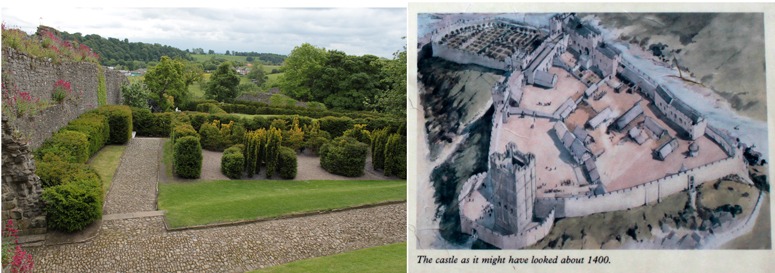

The cultural history of gardens is an interesting topic but I do not see why it should be detached from the design history of ‘how and why gardens took their present form’ (see comment on John Dixon Hunt’s use of the term cultural history). One could write cultural histories of furniture, or milk bottles, but they would not serve as substitutes for design history. So why separate the two approaches to history? My impression is that cultural historians have less appreciation of design than design historians have of culture. They tend to be ‘words people’ instead of ‘word and image’ people – and they don’t seem very good at reading plans. My recommendation to someone taking up garden history is to begin by measuring, drawing, photographing and writing about a single historic garden, including an account of the cultural context in which it was formed. From the other end of the telescope, I believe designers should have a broad appreciation of the cultural, technical and artistic context in which they are working.