The principle of involving school children in the landscape and garden design for the space outside their classrooms applies in every land. This video illustrates the involvement of children from the Druk White Lotus School in Ladakh India. There are many reasons for involving school children in the design of school grounds: (1) the children are creative – they know what they like to look at and what facilities they like to have (2) the children learn to take responsibility for their environment (3) the children have an involvment with the natural world (4) the children learn technical skills (5) with luck, some of the children will go on to become landscape architects, taking responsibility for the conservation and improvement of Planet Earth.

Category Archives: Buddhist gardens and environmental ethics

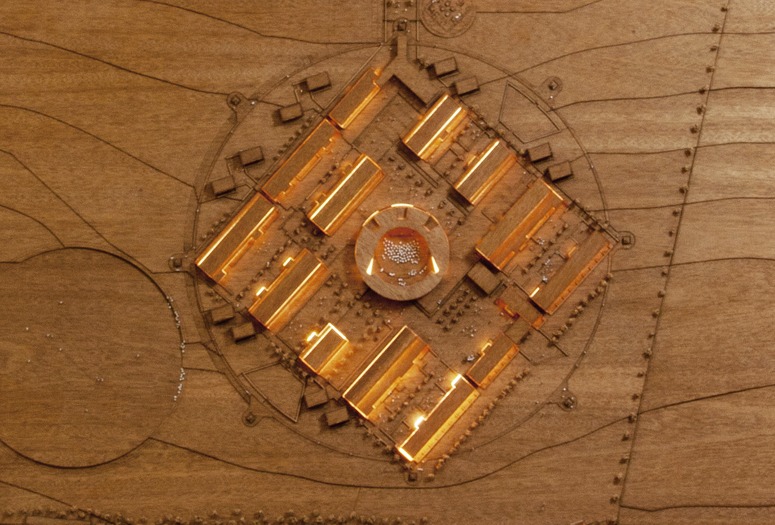

DWLS Dragon Garden in Shey, Ladakh, for the Druk White Lotus School

The architectural layout of the Druk White Lotus School, designed by Arup Associates, is based on a mandala. In the Sanskrit of the Rig Veda, the sections were called mandalas, meaning ‘cycles’ or ‘chapters’, rather as TS Eliot divided his Four Quartets into sections. The Rig Veda poems are often described as hymns and were receited by nomads on ritual occasions. When the nomads became settlers special places, including temples, were designed for rituals and they too became known as mandalas. Hindu and Buddhist sacred places, including stupas, are therefore said to have a mandala plan. In Tibetan and Ladakhi culture, which are Vajrayana Buddhist, a mandala is interpreted as a diagram which represents the geography of the cosmos.

The Druk White Lotus School (DWLS) was built in the desert outside Shey, the former capital of Ladakh. The buildings are nearing completion in 2012 and the next stage is to convert the school surroundings from desert to garden and landscape. Since the school was made under the auspices of the Drukpa Lineage, making a ‘Dragon Garden’ is appropriate. ‘Druk’ means ‘Dragon’ and ‘Druk-pa’ means ‘Dragon-person’, with the Lineage led by the Gyalwang Drukpa. What form a ‘Dragon Garden’ might have is yet to be determined.

The above video shows a school ritual (a morning assembly) taking place in a Dharma Wheel at the centre of the DWLS Mandala. Note that the children sitting beside the monk are using their hands to form the mudras. My impression is of kindly, enthusiastic and warm-hearted children – and I wish I had a similar impression when looking at school children in london.

Mandalas can take many forms and can be made in many ways. The below image shows coloured sands used to make a sand mandala.

A model of the mandala section of the plan for the Druk White Lotus School, by Arup Associates.

The placement of Buddhist stupas as landscape architecture

Having wondered for some time whether the design and siting of the pyramids at Giza was conceived as a ‘stylization’ of sand dunes on the boundary between the Red Land (desert) and the Black Land (farmed land), I timidly kept the idea to myself until Charles Jencks put forward the same idea. Now I wonder if the largest stupa field in Ladakh (above, at Shey) was conceived as a stylization of a mountain range. The stupas have this appearance but there are many considerations:

Having wondered for some time whether the design and siting of the pyramids at Giza was conceived as a ‘stylization’ of sand dunes on the boundary between the Red Land (desert) and the Black Land (farmed land), I timidly kept the idea to myself until Charles Jencks put forward the same idea. Now I wonder if the largest stupa field in Ladakh (above, at Shey) was conceived as a stylization of a mountain range. The stupas have this appearance but there are many considerations:

- Hindu gods are associated with mountains

- Buddhism does not have creator gods but draws much from Hindus ideas

- Stupas are symbols of the Buddha’s presence

- Nirvana is represented in Buddhist art as being in a mountainous region

- Mt Kailash is sacred to Hindus and Buddhists

An interesting aspect of Ladakh is that it has no tradition of making ‘pleasure gardens’ but the whole country appears to have been conceived as a garden.

The Buddhist cave at Phuktal Gompa (Phugtal Monastery)

The great cave of Phuktal Gompa in Ladakh has a sacred spring within. The monastery is said to have been built here because there was a forest on the slopes above, from which a lone tree survives. The cave is supposed to house the spirit of the first guru, Rimpoche.

Caves have a special place in Buddhism, because wandering monks used them for prayer, meditation and rest, and Ngawang Tsering (1717-94) wrote that: ‘Nurtured as sons of mountain solitude they dressed in clouds and mist and wore as hats deserted caves. Totally unconcerned with the world’s ways and mundane happiness they contemplated impermanence to create a sense of urgency and thus to make the best use of their life time. Meditation on the ominpresence of death served as a pillow and they wrapped themselves up in the cloth of mindfulness of karma. The mats which they spread were their awareness of the disadvantages of samsara which they likened to a whirlpool or a tapering flame. I sing my songs to induce kings to rule with the ten virtues, for the sake of the lowly so that each according to his capacity may rejoice in the Dharma, for the sake of the teachers pointing them to tantras, sutras and teachings, for the sake of earnest meditators that they may realise equanimity and insight, for the sake of the yogins with clear perception that they may be endowed with supreme vision action and function’

Image courtesy Kateharris