The enclosure on Vulture Peak Rajgir, India is believed to the be the place where the Buddha delivered the teaching recorded in the Heart Sutra. It contains the famous lines:

The enclosure on Vulture Peak Rajgir, India is believed to the be the place where the Buddha delivered the teaching recorded in the Heart Sutra. It contains the famous lines:

Form is emptiness, emptiness is form

Emptiness is not separate from form, form is not separate from emptiness

Whatever is form is emptiness, whatever is emptiness is form

The phrasaeology is meant to induce meditation. ‘Emptiness’ (Śūnyatā) may be interpreted in relation to the Buddhist concept of non-self (Anatta). Nothing we see has a separate ‘self’. Everything is inter-connected. The lines embody a paradox and this may be deliberate – because there is so much about the nature of the universe which cannot be understood. My own understanding of the lines is as follows:

– objects appear to have form but, because they are connected to everything else, this is an illusion

– the ‘everything else’ to which objects are connected can only be perceived through forms

This gives the lines from the Heart Sutra a relationship with Plato’s Theory of Forms and with the modern distinction between particulars and universals. We might say that universials are known only from particulars and that particulars are understood only when they can belong to universal categories. The favourte example is cats (see Fig 1). We only know the universal ‘cattiness’ through particular examples and we only know that particular cats ARE cats because of our acquiaintance with the universal form of cats.

Assuming I have interpreted the Buddha and Plato correctly, I am more attracted to the Buddhist version. Plato conceived the forms as eternal and unchanging. For a landscape architect or garden designer this is unappealing. It implies that all possible forms and designs already exist. The Buddhist version gives important positions both to the form which a designer ‘assembles’ and to the inter-connected cosmos (I almost wrote ‘compost’) from which the elements are drawn – and to which they will return. Forms have no ‘self’; they change every instant; they are impermanent (annica). Modern science confirms that everything is in flux. We notice it more in outdoor than indoor environments. With time the fourth dimension, landscape design appears to be a four-dimensional art.

The photo is from Wikipedia, with thanks. The design uses one of the primary Platonic forms: the square. Compare it with the photo of St Francis, below. Monasticism was a Buddhist idea and the monks seem to belong to the Axial Age, of the Buddha, Plato, Confucius and the author(s) of the Old Testament. Or do they belong to an even earlier age when India rishis meditated in forests, caves and mountain retreats? And why was it such a great period in the history of philosophy and religion? Should philosophers and religious leaders – and landscape designers – work in the great outdoors, instead of in fusty musty offices? Yes. Form is emptiness and emptiness is form.

Category Archives: Buddhist gardens and environmental ethics

Lynn Townsend White, environmental ethics, Christianity and Buddhism

I have mentioned Lynn Townsend White several times in this blog without, I am sorry to say, having read his 1966 article (see comments re Buddhism and re Christianity). It is available online and I recommend it The Historical Roots of Our Ecological Crisis Lynn White, Jr. As a historian, he is in the same league as Lewis Mumford and Sigfried Giedion but is field of view is wider, because he is a historian of ideas with an interest in the environment, rather than the other way about. Here is the famous passage from White’s paper, in bold, with the sentences which precede dnd follow it in italics:

To a Christian a tree can be no more than a physical fact. The whole concept of the sacred grove is alien to Christianity and to the ethos of the West. For nearly 2 millennia Christian missionaries have been chopping down sacred groves, which are idolatrous because they assume spirit in nature.

What we do about ecology depends on our ideas of the man-nature relationship. More science and more technology are not going to get us out of the present ecologic crisis until we find a new religion, or rethink our old one. The beatniks, who are the basic revolutionaries of our t ime, show a sound instinct in their affinity for Zen Buddhism, which conceives of the man-nature relationship as very nearly the mirror image of the Christian view. Zen, however, is as deeply conditioned by Asian history as Christianity is by the experience of the West, and I am dubious of its viability among us.

Possibly we should ponder the greatest radical in Christian history since Christ: Saint Francis of Assisi. The prime miracle of Saint Francis is the fact that he did not end at the stake, as many of his left-wing followers did. He was so clearly heretical that a General of the Franciscan Order, Saint Bonavlentura, a great and perceptive Christian, tried to suppress the early accounts of Franciscanism. The key to an understanding of Francis is his belief in the virtue of humility–not merely for the individual but for man as a species. Francis tried to depose man from his monarchy over creation and set up a democracy of all God’s creatures.

With this in mind, it is heartening that the new Pope has taken the name Francis. Pope Francis and St Francis of Assisi are the best hopes for Environmental Christianity – and possibly for the world environment. If Lynn White is correct that Christian beliefs underlie the attitude to the environment of Post-Christians and Non-Christians around the world, then a re-orientation of Christianity around St Francis could contribute much to ‘saving the planet’. Let’s hope this will include a new attitude to birth control. If the catholic church does not want to use modern technology for this purpose then, as in old Tibet, it could be done by having a very large population of non-breeding monks and nuns. Like St Francis, they could love animals. White went on to write that

Both our present science and our present technology are so tinctured with orthodox Christian arrogance toward nature that no solution for our ecologic crisis can be expected from them alone. Since the roots of our trouble are so largely religious, the remedy must also be essentially religious, whether we call it that or not. We must rethink and refeel our nature and destiny. The profoundly religious, but heretical, sense of the primitive Franciscans for the spiritual autonomy of all parts of nature

may point a direction. I propose Francis as a patron saint for ecologists.

Environmental Buddhism, landscape architecture and the Gyama Valley mining disaster in Tibet

I have been reading about Buddhist environmentalism recently. The divergent views can be summarised as follows:

- Many western commentators believe that Buddhism is a wholly environment-friendly faith, because of the belief in the ‘oneness’ of the world.

- Some western commentators (notably Ian Harris) argue that there is scaracely any basis for an environmental ethic in Early Buddhism, because it is a nihilistic faith with a soteriological emphasis on escaping from this world, rather than trying to improve it.

- The Dalai Lama and many other Buddhist leaders are wholehearted supporters of environmental ethics and see the ideas as inherently Buddhist.

In reading about the Dalai Lama’s views I came across this comment: “Now, environmental problems are something new to me. When we were in Tibet, we always considered the environment pure. For Tibetans, whenever we saw a stream of water in Tibet, there was no question as to whether it was safe for drinking or not. However, it was different when we reached India and other places. For example, Switzerland is a very beautiful and impressive country, yet, people say “Don’t drink the water from this stream, it is polluted!”… I remember in Lhasa when I was young, some Nepalese did a little hunting arid fishing because they were not very much concerned with Tibetan laws. Otherwise there was a real safety for animals at that time. There is a strange story. Chinese farmers and road builders who came to Tibet after 1959 were very fond of meat. They usually went hunting birds, such as ducks, wearing Chinese army uniform or Chinese clothes. These clothes startled the birds and made them immediately flyaway. Eventually these hunters were forced to wear Tibetan dress. This is a true story! Such things happened, especially during the 1970’s and 80’s, when there were still large numbers of birds. Recently, a few thousand Tibetans from India went to their native places in Tibet. When they returned, they all told the same story. They said that about forty or fifty years ago there were huge forest covers in their native areas. Now all these richly forested mountains have become bald like a monk’s head. No more tall trees. In some cases the roots of the trees are even uprooted and taken away! This is the present situation. In the past, there were big herds of animals to be seen in Tibet, but few remain today. Therefore much has changed.”

Just after reading this passage I heard of the mining disaster in the Gyama Valley (30 March 2013) in which 83 people died. This led me to look for photographs of forest clearance in Tibet, to see if this could be the cause of the problem, since deforestation so often causes erosion and flooding. I could not find any photographs, so this blog post lacks an illustration. Compared to most of the world’s religions, Buddhism has the great advantage of accepting endless change (anicca) as a fundamental characteristic of the universe and of Buddhism. Islam, by way of contrast, takes the Quran as having been passed from God to Gabriel to Muhammad. This allows some scope for new interpretations (eg in the Hadith) but none for change. Islam is fortunate in having a good base for an environmental ethic. In my view, Buddhism is also in a strong position in this regard and I hope that the reviving popularity of Buddhism in China will encourage the development of environmental ethics everywhere – and of a Buddhist approach to landscape architecture – and mining operations are a special opportunity. Christians have been working at the problem of developing an environmental ethic but have been handicapped by Lynn White’s critical stance.

See the Wiki entry on Religion and environmentalism. Religions often find it difficult to come together but environmentalism offers great opportunities in this regard. Because ‘The Environment’ was not a problem in The Axial Age there are relatively few historical positions which need to be defended.

Environmental Green eco-Buddhism and the ethics of landscape architecture and garden design

Buddhism is a belief system. Though sometimes described as a ‘religion’ the Buddha’s teaching had no creation story and no gods. Nor did the Buddha want to be ‘worshiped’. Some Buddhist sects became more like the other religions but CHANGE (anicca) is an essential characteristic of Buddhism – and one which favours the development of green, environmental, eco-Buddhism. Buddhism can be compared to open-source software in this respect. Everyone can draw upon the core code and everyone can make contributions. Buddhists have never fought each other in the way that Protestants have fought Catholics and Shias have fought Sunnis. Without giving them a specifically Buddhist interpretation, it is evident that the core principles could be of use to the environmental professions come from the Ayran Path:

1. Right view

2. Right intention

3. Right speech

4. Right action

5. Right livelihood

6. Right effort

7. Right mindfulness

8. Right concentration

Buddhism has the very attractive characteristic of being kind to animals. Wiki puts it like this ‘Animals have always been regarded in Buddhist thought as sentient beings, different in their intellectual ability than humans but no less capable of feeling suffering. Furthermore, animals possess Buddha nature (according to the Mahāyāna school) and therefore an equal potential to become enlightened.’

Buddhism dates from what Karl Jaspers called the Axial Age – as do the origins of the world’s other major philosophical and belief systems. That period seems to have had a talent for beliefs equaling our own priod’s talent in science, which may be a reason for looking so far back to find sound ethical principles. It is of interest that the medical profession dates from the Axial Age and has a good base in the Hippocratic Oath. I once had a go at adapting the Hippocratic Oath for landscape architecture.

Wiki gives the following figures for the numbers of adherents of the major world faiths:

Christianity 2,000–2,200

Islam 1,570–1,650

Hinduism 828–1,000 I

Buddhism 400–500

Nobody knows how many Chinese people are, to a greater or lesser extent, followers of Buddhist ideas. If the number is large, Buddhism could move up the rankings. My impression is that ‘communist China’ is now building more Buddhist temples than any country has ever built at any point in history.

Buddhist Gardens and the Dragon Garden in Shey, Ladakh

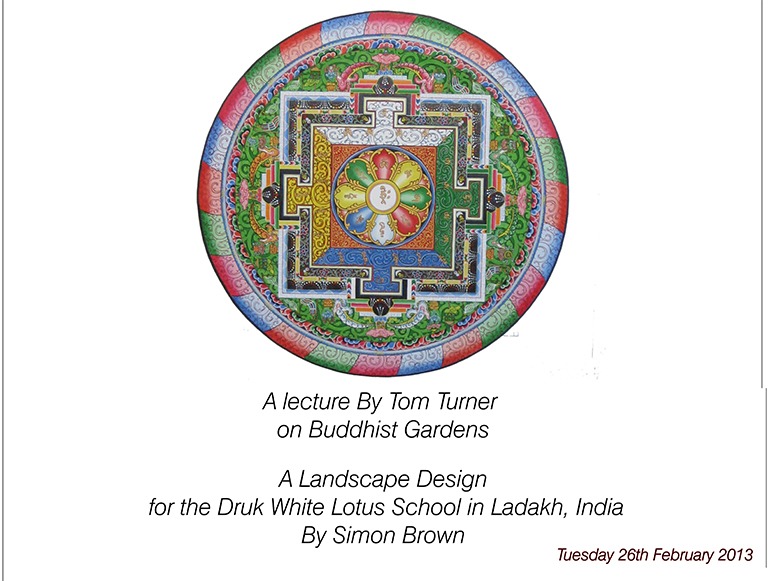

If anyone would like a (free) ticket, I am giving a lecture about the influence of Buddhism on garden design – to be followed with a lecture by Simon Drury-Brown on the design of the Dragon Garden for the Druk White Lotus School in Ladakh, India. Tickets are available from Eventbrite. The design of the school, by Arup Associates, is based on a mandala. The design of the garden extends the mandala concept and gives it a wider application.

The great Italian scholar of Tibetan Buddhism, Giuseppe Tucci, explained the mandala concept in a way which makes it well suited to forming the basis for a landscape plan for a school community. Tucci wrote that ‘First and foremost, a mandala delineates a consecrated superficies and protects it from invasion by disintegrating forces symbolized in demoniacal cycles. But a mandala is much more than just a consecrated area that must be kept pure for ritual and liturgical ends. It is, above all, a map of the cosmos. It is the whole universe in its essential plan, in its process of emanation and of reabsorption. The universe not only in its inert spatial expanse, but as temporal revolution and both as a vital lprocess which develops from an essential Principle and ratates round a central axis, Mount Sumeru, the axis of the world on which the sky rests and which sinks its roots into the mysterious substratum. This is a conception common to all Asia and to which clarity and precision have been lent by the cosmological ideas expressed in the Mesopotamian zikurrats and reflected in the plan of the Iranian rulers’ imperial city, and thence in the ideal image of the palace of the cakravartin, the ‘Universal Monarch’ of Indian tradition‘. The Druk School will become a place where teachers, students and visitors are encouraged to think about the nature of the cosmos and the nature of human life. The landscape design is being developed by landscape architecture staff and students from the Univesity of Greenwich. Design, construction and fund-raising are managed by a UK Charity, the Drukpa Trust. The school has won a sheaf of international awards. The architects, Arup Associates, explain that

- Classrooms face the morning sun to make the most of natural light and heat.

- The school is largely self-sufficient in energy.

- Two boreholes and solar pumps supply the school site with all the water it needs.

Mandala landscapes for stupas, temples, gardens and the Druk White Lotus School DWLS

We tend to think of a mandala (मण्डल) as a graphic pattern, though the Sanskrit derivation of the word is from the ‘cycles’ or ‘circles’ (ie ‘sections’ or ‘books’) of the Rig Veda. The Vedas were hymns recited on ritual occasions. Mandala patterns were developed to symbolise the rituals and the ideas underying the rituals. Buddhists took on the idea from Hindus and used mandala patterns in the design of stupas (chortens), tankas and many other things. Used in this way, a mandala symbolises the geography of the cosmos. Early mandala patterns had a lotus flower with open petals and the Buddha at its centre. Circles and squares were added and a mandala came to represent the four material elements of the universe (earth, water, fire, wind) with Mount sumeru as the world axis. Energy moves in a cosmic dance from the centre to the periphery, and then back to the centre, encompassing inanimate and living things.

Buddhist Chinese and Japanese gardens are also mandalas. The word ‘Pagoda’ derives from ‘stupa’ and these gardens symbolise the cosmos, with the temple as a house for a Buddha. In later Chinese gardens temples evolved into garden pavilions for the delight of their owners.

A real landscape can also be a mandala, with the Lapchi region on the Nepal-Tibet border a famous example, which includes Milarepa’s Cave. Lapchi’s mandala landscape is conceived to have three sacred triangles formed by the sky, the earth and the three rivers. The central mountain is seen as the Palace of Chakrasamvara.

The landscape around the Druk White Lotus School in Ladakh can be thought of as an emerging mandala landscape.

- It has a modern mandala plan, by Arup and Arup Associates.

- It is in view of three famous Buddhist gompas: Shey, Thikse and Matho.

- It is in the valley of a sacred river: the Indus

Time lapse photography of Buddhist monks using coloured sand to produce a sand mandala (courtesy camera_obscura):

Tibetan Sand Mandala – Timelapse – 30 fps a video by camera_obscura [busy] on Flickr.