Buddhist garden design in Japan is the third of six videos on the relationship between Buddhism and the history of garden design.

Buddhism spread to Japan from China and Korea, as did the Chinese style of laying out cities, palaces, temples and gardens. Japanese gardens were often made for Buddhist monasteries, where they tend to be called Zen gardens, and for retired emperors who wished to live as abbots and conduct their preparation for the Pure Land and nirvana. The term ‘Zen garden’ was not used until the 1930s but has become very popular.

The influence of Buddhism on garden design is explained in my eBook on Buddhist gardens

Buddhist garden design in India, Sri Lanka and Nepal

Buddhist garden design in India, Sri Lanka and Nepal is the second of six videos on the relationship between Buddhism and the history of garden design.

Buddhism began in North India and, over the next 1500 years, almost died out in India. But it survived in Sri Lanka – which also has good examples of ancient Buddhist gardens used by monastic communities. See: Sigiriya, Polonnarauwa, Anuradhapura – Mahamegha Gardens (Mahamevuna Uyana),

The influence of Buddhism on garden design is explained in an eBook

The life of Siddhartha Gautama Buddha in Gardens

Buddhism is the world faith which has had most influence on gardens. This began in India and spread to China, Korea, Japan and other countries in South and East Asia. I have sketched these developments in an eBook and six videos, of which this is the first.

The Shock of the New – Freeway

The freeway for the electric and hybrid car need not be the highway we are used to.There is no reason why it might not be encased in landscape when the view out is less than appealing: concrete noise barriers or the back of suburban areas or some of the more hostile industrial areas of our large cities.There is no reason why the drive to work need be monotonous…and why the landscape views might not be considered in the same way as a promenade through a garden. We should take advantage of what nature provides and the cultural landscapes we have created.

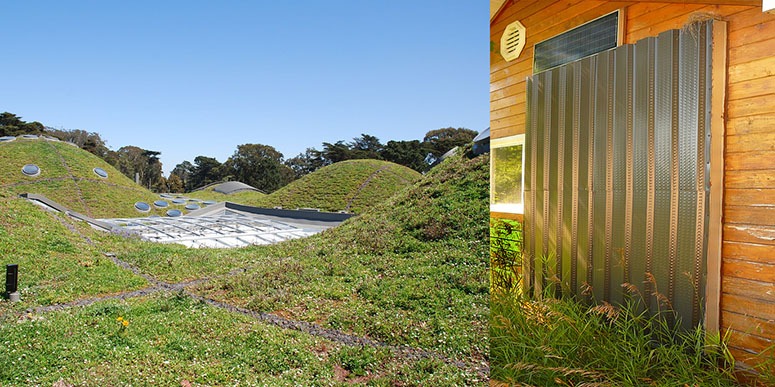

Sustainable green roofs and solar walls in urban landscape design

Amazing but true: the price of solar panels after dropping at about 6% per year for a decade, the price of solar panels is now dropping at 20% per year. If this continues for 5 years solar power is going to be cheaper than coal power. But the cost of electricity transmission is not falling so it will be advantageous to have solar panels as close as possible to the buildings in which the electricity is used. So the likely future of urban design is: solar panels on the walls and vegetation of the roofs. No more dead walls and, since pv panels are reflective, we can look forward to sunlight being reflected into the previously dark corners of cities. Retaining the ‘matchbox’ form of recent cities would not be sensible. We can look forward to some entirely different urban forms and to a much fuller integration of landscape design with architectural design.

Images courtesy afagen and mgifford,

What is a 'Zen Buddhist garden'? and is the idea Japanese, Chinese or Western?

Wybe Kuitert, a notable scholar of Japanese garden history, has challenged the the theory that stone and gravel gardens, like Ryoan-ji, were inspired by Zen Buddhist ideas. He argues that the theory did not appear before the 1930s and that it then arose from an American scholar (Loraine Kuck) who was influenced by Japanese nationalist thinkers who wanted to argue that Japanese culture was more harmonious and less aggresive than western culture. I am persuaded by Kuitert’s account of the origins of the now-common classification of Ryoan-ji but doubtful that his alternative explanation is adequate. From a knowledge of Japan which is much less than Kuitert’s, it appears to me that (1) stone-and-gravel gardens are very likely to have been influenced by Chinese precedents (2) whether or not the Chinese precedents were specifically Chan (ie Zen) Buddhist, they were certainly influenced by Buddhist ideas and their Daoist parallels.

There are three difficulties in tracing the Chinese precedents of stone-and-gravel gardens: (1) so far as I know, there are no visual or records (2) there may be textual records of Buddhist gardens in Song China but, if so, they would have to be investigated by Chinese garden historians with the ability to find and read the relevant documents (3) research into the influence of Buddhism on Chinese gardens is not a popular field of research in China – because Chinese governments have very often wanted to downplay the influence of all foreigners on Chinese civilization.

I hope these questions will receive the attention they deserve someday. Here are some quotations from Kuitert to stimulate the necessary research (from Kuitert, W., Themes in the History of Japanese Garden Art University of Hawaii Press 2002). But, for what it is worth, my view is that the categorization ‘Zen Buddhist Garden’ is valid- unless and until better information becomes available.

p.130 ‘The Oriental supposedly sees himself not as an individual at war with his environment but rather as fundamentally a part of all that is about him.’

p.133 In previous chapters we have seen that the medieval garden makers were not devoted Zen priests but usually menial stoneworkers…

P.133 The present pages on the evolution of a scenic garden style, however, show that this is not the only interpretation. From the preceding it is clear that this type of garden stemmed in theory (and at least part of its practice) from the Chinese intellectual and literary canon of landscape art. The building of a garden was calculated intellectual activity, not an instantaneous act of religiously inspired intuition. It found its place in Zen temples and warrior residences because it enhanced a cultural ambiance. That its appreciation involved religious aspects rather than artistic ones is questionable. A Zen religious experience was interpreted in modern European terms of philosophy by Nishida. It was Suzuki who extended this interpretation to culture and the arts – thereby making the mistake of explaining the intent of the original creator of historical works of art with it. Kuck similarly stated that the Ryoan-ji garden is ‘the creation of an artistic and religious soul who was striving… to express the harmony of the universe’. With this statement she assigned the twentieth-century religious or aesthetic experience she felt on seeing the garden to the soul of a medieval garden maker. Kuck mixes her own historically determined interpretation with an old garden that came about in a completely different cultural setting.

The above photograph of Ryoan-ji is courtery jpellgen. It captures the aspect of the garden which attracts and mystifies western visitors: ‘Karesansui. Ryoan-ji in Kyoto has a world famous zen rock garden. Here you can see some of the simplicity that makes this garden so impressive. The position of the stones and the carefully maintained sand is a sight to behold. Ryoan-ji is a famous temple of the Rinzai branch of Zen Buddhism. It dates back to the 1400’s and was originally associated with the Fujiwara family (big suprise there). The most famous aspect of Ryoan-ji, however, is the karesansui (dry landscape) rock garden–believed to be the finest in the world. It contains 15 stones, although I had trouble finding the last one. Apparently, most people can only see 14 unless you have the right perspective of this 30mx10m garden.’