Garden design and the history of art

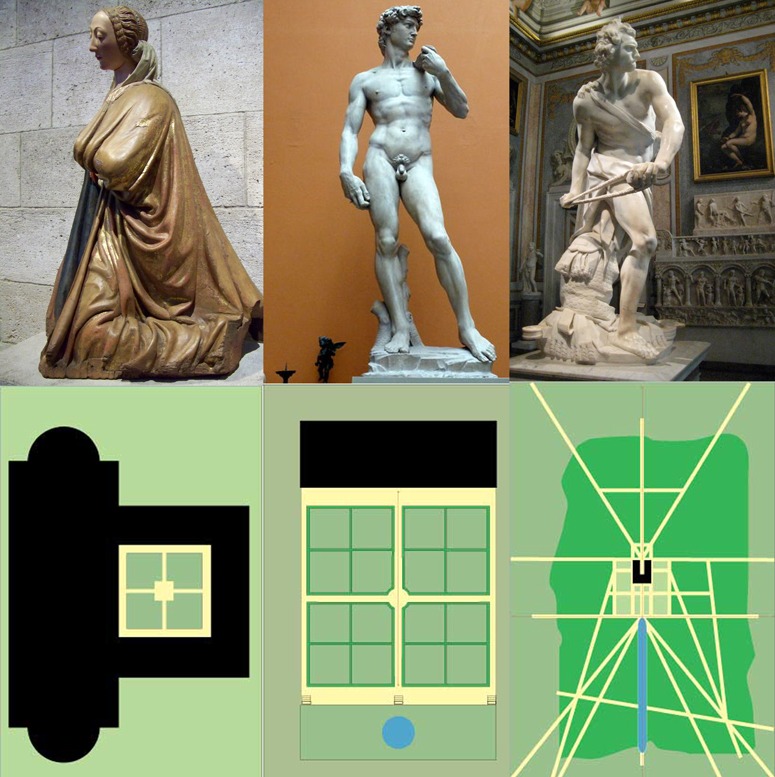

The top pictures show a medieval statue, Michaelangelo’s David and Bernini’s David.

The lower pictures show a medieval garden, a renaissance garden and a baroque garden.

The pairs represent the devotional attitude of the middle ages, the static calm of the renaissance the drama of the baroque.

I think there are closer parallels between the histories of gardens and fine art than between the histories of gardens and dynasties, which makes me doubtful about the categorisation of British gardens as Tudor, Stuart, Georgian, Victorian, Edwardian etc. Nor do I think kings and queens have had a leading role in the development of garden design. So why are royal names so popular in Britain? Are garden historians flunkies? And how do the Irish manage without royal names for garden styles?

I really enjoyed this blog and the saying ‘a picture paints a thousand words’ is so right here, these illustrations really explain these styles so clearly and well.

I also agree totally that the categorisation of gardens through the reign of the monarchs is confusing and explains nothing bar the time frame, Tudor or English Renaissance, the second title gives you a far better clue I would have thought.

The only King I can think of who played a part (I thought at first) in a design style was the French King Louis X1V, but thinking about this, I feel he may have known what he liked, wanted and disliked but did he lead the baroque in France, no. Louis really only ratified the designs of Le Notre and Mansart and provided the funds.

I may well be jumping the gun, but retain my hope that King Charles III will exceed the record of all his forebears by taking a leading role in garden design, landscape planning and landscape architecture. As Prince of Wales, he has, at Highgrove, made one of the twenty-first century’s most interesting gardens.

Charles already belongs to an elite group with a key role in garden history: the owner-designer who is able and willing to work with other designers.

Tom are you questioning the classic relationship between patron and artist? Perhaps the UK is experiencing another Elisabethan period or the a nascent Cameronesque style in art, architecture and landscape?

I think that for centuries commoners were never recognized as doing anything important. In the 18th century, for example, the only gardens worth mentioning always had a connection to rich and/or influential people like Alexander Pope, Kent, Capability Brown, and Repton. That’s why my hero is Loudon, who saw that middle class gardeners were worth considering.

Here in the States for decades we have written about Jefferson, Washington, Hamilton [Woodlands in Philadelphia] as gardeners. Not much focus on ‘vernacular’ gardens here. Even Downing was criticized as appealing to the rich in his design style. Thankfully today that has changed. We see value in gardens of any size, of any time. A new book about European immigrants and their gardens called Putting Down Roots gives much insight about ‘commoner’ garden style here in the state of Wisconsin in the 1800s.

Yes. Independence from patronage was one the progressions towards professionalisation of the disciplines including architecture and landscape and artistic practitioners including musicians, composers and painters.

In the UK professional architects were increasingly not gentleman architects (members of the nobility), educated via the Grand Tour, but instead trained via the articled system until architects themselves established the Architects Association to increase the standards of education.

[ http://www.aaschool.ac.uk/AALIFE/LIBRARY/aahistory.php ]

Thomas, thank you for your comment. Loudon is also a hero of mine. I love the way he went to visit great estates and, instead of fawning on the great man, went home and attacked him for the poor way in which he treated his gardeners. Though of course he praised them when appropriate. With regard to the eighteenth century, part of the problem is that much less information is available about the common people and their gardens.

Christine, I like to think of myself as a professional person – but I keep reminding myself of Adam Smith’s terrible words “People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices.” I don’t think this happened, or at least not to the same extent, in the days before clientage replaced patronage. Humphry Repton was on the cusp of this. The people he worked for were part-client and part-patron. It seems that he did the work they wanted and then sent a bill later. When the bills were not paid he was very resentful. I don’t know for sure but I have the impression that the clients thought that if they did not go ahead with his proposals then they had not entered into a patronage relationship – and did not need to pay him.

Yes. I remember reading of a very unfortuneate court painter [of murals] who had terrible trouble getting paid for his work and used to produce flattering schemas of his patron in the hope of appealing to their better nature!

Nicholas Hilliard is an example of a 16th century court painter. It seems even at this time in history there was a degree of professional independence from the Court.

[ http://www.enotes.com/topic/Nicholas_Hilliard ]

It is interesting to note that he also tutored ‘amaetuer’ painters. Amaetuer’s were more likely to be children (particularly females) of the nobility who were expected to be graced with a knowledge of the arts. Sometimes they were accomplished, and other times not:

“…women should “read neither poetry nor politics — nothing but books of piety and cookery” (leavened with the conventional “accomplishments” of “music — drawing — dancing”).”

The education system at this time (at all levels) was particularly limited and relied on governnesses, private tutors and the occasional boarding school. Education was largely restricted to males.

I have done a blog post about artistic patronage http://www.gardenvisit.com/blog/2011/11/15/patronage-and-the-lovliest-dolphin-and-naked-boy-fountain-in-the-world/

Re the governess education system, it lasted a long time. My Granny enjoyed the educational curriculum you describe (and also learned some foreign languages).

Was this the granny that was a suffragette? Or did this particular granny do other equally amazing things? (ie sculpt?)

No – my great aunt was a suffragette. I do not know what my Granny thought about women’s suffrage but guess she was in favour: she always wished she had been a man, because ‘men can do things’ – she only had 5 children!

Yes. But the problem with only having five children, is that your grandfather only had 5 children too!

I don’t think he saw much of ‘his’ children.

Pingback: The Changing Styles of Garden Design | The Hadlow College Blog