Salisbury Cathedral, The Shard (with a cross) and the Albert Memorial as Christian architectural symbols in an urban landscape

If you build a skyscaper in London you can expect a shovel of reviews. Here is a selection of opinions about the symbolic impact of Renzo Piano’s Shard on London’s landscape.

Tom Turner: If The Shard had a Christian cross on top most of the critics would change their minds

Nathan Hurst: The Shard is an irregular pyramid with a glass exterior, evoking a shard of glass.

Fergus Feilden: I find the Shard lacks soul

Richard Rogers: The Shard is the most beautiful addition to the London skyline.

Owen Hatherley: The Shard is rammed unforgivingly into Southwark

Peter Buchanan: The Shard is much too big, as is Piano’s building rising beside it, and completely out of character with the surrounding area − the evocation of spires and sails is fatuous.

Simon Jenkins: This tower is anarchy. It conforms to no planning policy. It marks no architectural focus or rond-point.

Paul Finch: Like any icon, the Shard demands attention and has received it in spades from London cab drivers (split views), architects (benefit of the doubt), and the non-fraternity of architectural critics puzzled by this south-of-the-Thames phenomenon.

Terry Farrell: In its overall shape, the tower is to my mind a bit of a 1960s Dan Dare version but as with all Renzo’s buildings it has its own elegance.

Simon Allford: I am delighted to see it standing tall on the skyline in an unexpected place confidently breaking rules.

Patrik Schumacher: The form is insufficiently motivated. The project seems to sacrifice efficiency for the formal purity of the pyramid.

Jonathan Glancey: The Shard is in the wrong place. It would be better off in Shanghai or Dubai.

Aditya Chakrabortty: It’s expensive. It’s off-limits. It’s largely owned by people who don’t live here. And it is the perfect metaphor for what our capital is becoming.

Chris Leadbeater: Henry VIII would be furious. Apoplectic. Red-faced with rage. Heads would surely roll.

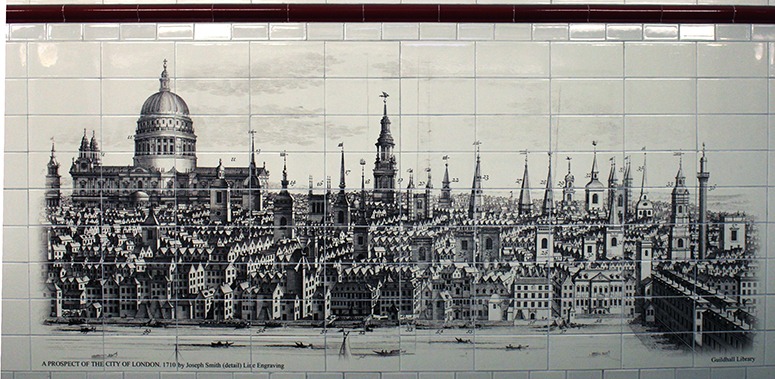

My guess is reviewers can be placed in two camps: left-wing and right-wing. Aesthetic conservatives would be happy to see a traditional spire towering of London, as the spire of Old St Paul’s once did. Aesthetic lefties enjoy breaks with tradition and feel sick at the use of a traditional building forms in the twenty-first century. Both groups of critics are happy to sneer at Towers of Mamon and/or at foreign involvement in London. Symbols have a profound influence on aesthetic judgements. While the UK economy has languished for a century, London’s economy has rarely paused since the time of Henry VII. It remains one of the most financially productive places on earth and subsidises what remains of the British Empire (including the North of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.)