Pompeii would be in much better condition today if had never been excavated – and the same is true of a great many archaeological sites. Too many archaeologists are paid to publish papers or to support the tourist industry. They talk about conservation, endlessly, but they do far more good than harm. Since garden archaeologists have so few ancient gardens to damage, they should set an example to the archaeological profession by making reconstructions of ancient gardens. Images, text and digital reconstructions are all useful but nothing is as good as a 1:1 reconstruction near, but never on, the archaeological remains. The lake dwellings in the above photographs are reconstructions of dwellings from the Bronze and Stone Ages. (at the Pfahlbau Museum Unteruhldingen, Germany). Image courtesy Derek

Category Archives: garden history

Christianity, music, sacred trees, garden design and the architecture of a new landscape

Dorothy Frances Gurney wrote that “One is nearer God’s heart in a garden/Than anywhere else on earth.” Her father and husband were Anglican priests – so some might read this as her criticism of male egotism! Or one might think that the Miserere sung in Europe’s most perfect building (I would give this award to King’s College Chapel) takes you closer to ‘God’s heart’. The Vatican kept the music private for centuries. Mozart went there, memorized the score, went home and wrote it down.

Christianiaty has a chequered relationship with art and gardens. Gardens are celebrated in the Song of Solomon and the Garden of Eden story (see blog post) but the Christians felled sacred trees throughout Europe and have never given gardens the support they have had in Buddhism and Islam. Last time I saw the garden of Lambeth Palace (London home of the head of the Church of England) it was an utter disgrace – and most Church of England cloister garths are badly or inappropriately managed. Anglican Christianity is losing support for a host of reasons but Christian music is entirely holding its own – always making the case for a simple, idealistic and joyful approach to the world. The drive for perfect simplicity + imaginative creativity, as seen in Kings College Chapel, may be connected to Bill Gates’ obsevation that he liked Cambridge because it had won more Nobel prizes than the rest of Europe put together.

My own view, as a ninth generation skeptic, is that while there is something utterly wonderful about Christianity, it is in urgent need of renewal ( perhaps a ‘New New’ Testment). So I wonder what garden designers can contribute to the architecture of a new landscape.

We have had apologies for the Crusades and the Inquisition. Please can we now have a full and frank apology for the felling of Sacred Trees – and then a quest to produce a contextual design as perfect as the singing of the Miserere in King’s College Chapel. This is my Christmas and New Year wish for 2010, made on the day after the pagan New Year (21 December) and therefore a day of hope for the return of warmth, sunshine and flowers. London is having a cold, wet and slushy end to a year of economic turmoil.

PS A different musical response to the nature of the world, kindly drawn to my attention by a Chinese landscape architect, can he heard in the beautiful Yuzhou Changwan (‘Singing at night on fishing boat’):

PPS If the two pieces of music are run similtaneously the result is curious East-West mashup.

A Cultural History of Italian Gardens by John Dixon Hunt – book review

John Dixon Hunt edited a book on The Italian Garden: art, design and culture (Cambridge University Press, 1996). He is now working with Michael Leslie on a six volume Cultural History of Gardens (scheduled to be published by Berg Publishers in 2011): The blurb states that “Michael Leslie is Professor of English at Rhodes College. He was founding co-editor of the Journal of Garden History (now Studies in the History of Gardens and Designed Landscapes – SHGDL) and Senior Fellow in Landscape Architecture at Dumbarton Oaks (Harvard). John Dixon Hunt is Professor of Landscape Architecture at University of Pennsylvania. He was previously Director of Studies in Landscape Architecture at Dumbarton Oaks and is editor of the journal, SHGDL and series editor of the Penn Studies in Landscape Architecture.”

The book on Italian Garden indicates what is meant by the term ‘cultural history’ . It is the work of ‘a distinguished group of Italian, American, English and German scholars, with different backgrounds in art history, literature, architecture, planning and cultural history’. I appreciate the study of every aspect of gardens but am most interested in the questions of how and why they were designed, which appears not to be a significant aspect of ‘cultural history’.

The 1996 Italian Garden Chapter of most interest to me is D R Edward Wright’s ‘Some Medici gardens of the Florentine Renaissance: an essay in post-aesthetic interpretation’. He concentrates on the social use of gardens, a topic of much concern to designers but often neglected by garden historians. Wright comments that it is ‘as if human use of planned environments was a mere afterthought to an essentially artistic endeavour’. He distinguishes between the high society uses of the Boboli Garden, the relatively pastoral use of the Villa Castello – as a health resort, and the use of Pratolino as a hunting park. I hope the projected Cultural History of Gardens has more chapters like this and fewer literary canapes than Italian Garden.

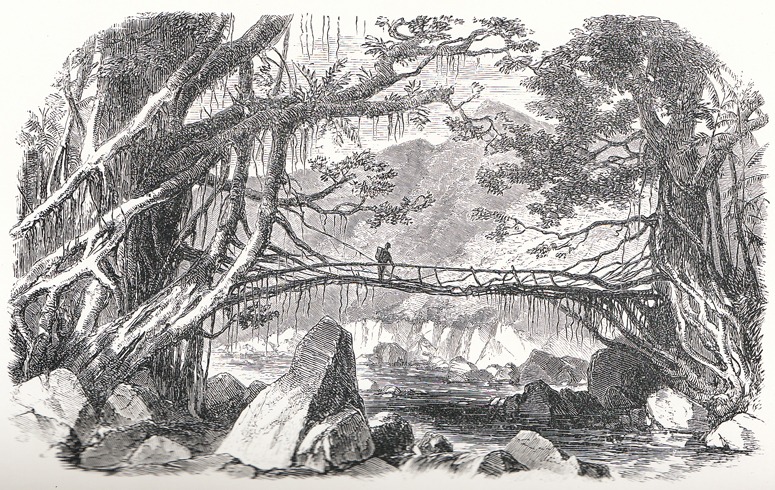

The landscape architecture of sacred groves in Ancient Greece and modern London

Western cities are full of echos Greek architecture, almost all inspired by surviving Greek temples which were built in sanctuaries and sacred groves as houses for gods. Greek temples were not buildings in which people congregated to pray, as Christians and Muslims congregate. As Vincent Scully argues, temples were located in landscapes which were sacred long before the temples were built. Often, these places also had sacred groves, comprising either wild or planted trees, before the temples were built. I therefore suggest that all those cities with echos of Greek architecture should also have sacred groves. They would be wonderful gestures to the origins of western landscape architecture. London’s Waterloo Quarter has commissioned a Christmas Forest for 2009, thankfully turning its back on all those centuries in which the Christians felled sacred groves. See Waterloo Forest designed by landscape architects naganJohnson.

Pierre Bonnechere writes that ‘At present the sacred grove of Nemea is the only one archaeology can claim to have discovered with certainty. Called an alsos from the first literary evidence, the site was landscaped [ie planted] in the fifth and fourth centuries B.C., and perhaps earlier: twenty-three planting pits, carved into the crushed rock at the south of Zeus’s temple, were uncovered and found to contain carbonized roots of cypress (or perhaps fir) trees. The excavators have now replanted the site, restoring its former appearance (Fig 1: they have followed Pausanias, who mentioned cypress trees in the second century AD)’ (Conan, M., Sacred gardens and landscapes: ritual and agency 2007 p.18). See also Sacred Groves: Sacrifice and the Order of Nature in Ancient Greek Landscapes 2007 Barnett R. Landscape Journal, 26:2. University of Wisconsin Press, 252-269 (kindly made available by Rod Barnett at http://www.rodbarnett.co.nz/texts/)

Image courtesy Miriam Mollerus

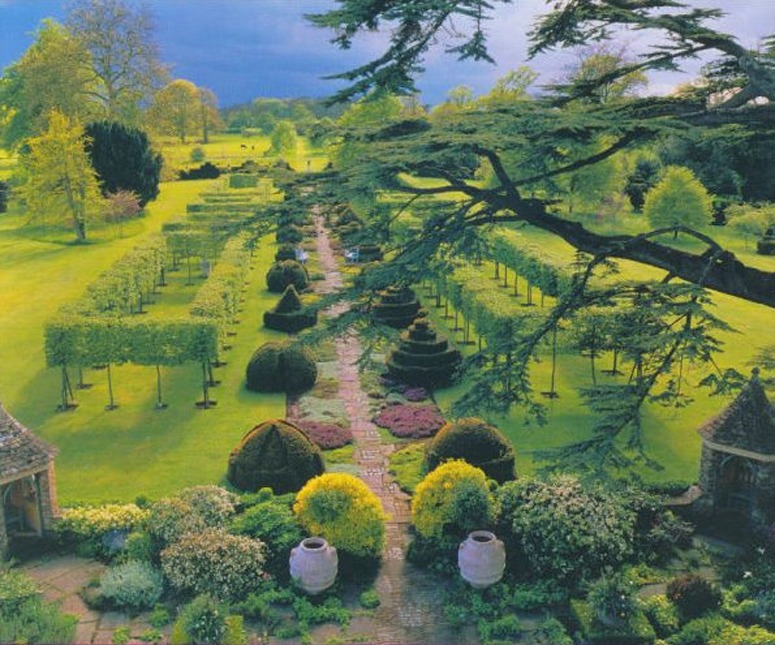

Prince Charles' Postmodern Garden Design for Highgrove

The cover of The Garden At Highgrove by the Prince of Wales and Candida Lycett Green illustrates the postmodern character of even the central vista (the cedar tree has since died)

Gods bless the Prince of Wales

I once wrote that ‘Royal leadership in the art of garden design began to decline after the accession of George I in 1714‘. His successors lacked the garden enthusiasm of their predecessors. No one could say this of Prince Charles. With talent and resources, he is making one of England’s great gardens. Should he become Charles III, as I hope, he will be the most talented garden designer ever to sit on the throne of England or Great Britian. He has substantial talents in garden design, landscape architecture and landscape painting. Charles is already The Green Prince. But will future historians state that ‘royal leadership in the art of garden design resumed when the Duchy of Cornwall bought Highgrove from Maurice Macmillan in 1980’? It is possible. But it is too early to judge. The Prince has, he tells us, put his soul into Highgrove. You can find a few images on the web and many in his book but unless you manage a visit, as I was lucky to do, you will not get a good idea of the garden. With 6 full-time gardeners and 4 part-time gardeners, it is a fast-changing and, as yet, a rather admirably untidy place.

I will try to put my analysis into the standard format of a design critic and teacher: classifying the approach, saying what is good, saying what is not so good, and making suggestions re ‘what could do with further thought’.

The style of the Highgrove garden

The house dates from the 1790s and the design theory underlying the garden dates from much the same time. Humphry Repton, who once worked for a Prince of Wales, would have strongly supported the use of a compartmented structure and, unlike Arts and Crafts compartments, they would have had design themes. I do not doubt that Repton would have approved the use of contemporary themes at Highgrove – and the view of Tetbury steeple from the front of the house is uncannily like a Reptonian sketch. But the visual character of Highgrove is uncompromisingly postmodern – to a far greater extent than the Abbey Garden in nearby Malmesbury by the brash postmodern developer-architect Ian Pollard. In detail, it may well be that Prince Charles has drawn inspiration from his annual visits to the Chelsea Flower Show and, perhaps, from Ian Hamilton Finlay’s Little Sparta and from the work of Geoffrey Jellicoe.

What’s good about the Highgrove garden design

The Prince has been very brave. His skill with pen and brush have educated a discerning eye and a creative imagination, able and willing to work as a patron for talented craftworkers. Individual compartments are highly experimental, with some notable successes and some requiring further thought. He also has a grand theme – sustainability- which, it must be hoped, will unite the compartments into what could become the greatest Postmodern Garden in Britain. At present Portrack, by Charles Jencks, is its chief rival.

What’s not so good about the Highgrove garden design

The Highgrove garden lacks spatial coherence. This flaw may be a consequence of its youth. But it may also result from the lack of a ‘master plan’ at the outset of the project. It is perfectly logical for a Postmodern garden to be without a master plan but its lack may diminish the eventual quality of the design.

Respectful suggestions for the Highgrove garden

I saw Highgrove in early autumn. It may be that a flowing springtime meadow, billowing around the geometrical core, gives more coherence. But I doubt if this would be enough, even though Miriam Rothschild advised on the composition and management of the wildflowers. My first suggestion to Prince Charles is to get some feint outlines of the garden plan printed onto the best watercolour paper and then to lay some washes to create a shape and a pattern for this space. My second suggestion is to give some more thought to the pedestrian circulation. This should be done first by user analysis (records of walks: by residents, visitors, staff, animals etc) to plot desire lines, and then by the Prince, if he can find the time, doing a series of quick watercolours to show views along a ‘processional route’ (ie a recommend route for visitors). They should be arranged in sequence and used as a design tool for future projects. Eventually, it might be found that they can be edited to tell a story.

PS I use ‘gods’ instead of ‘god’ in the heading for this post for several reasons (1) Prince Charles has stated his desire to be the Defender of Faiths, rather than Defender of the Faith (Fidei defensor), (2) many ‘gods’ appear to be respected and represented at Highgrove, (3) Christianity has not been a fruitful religion with regard to garden design.

PPS I also liked the Orchard Room designed by Charles Morris and consider Jonathan Glancey’s piece on A royal bungalow in the Tesco style bigoted.