Apart from fig leaves, bougainvillia and sin, what was planted in the Garden of Eden? We can say little about the layout but something about the location and something about the planting design. It may be argued that ‘every tree that is pleasant to the sight, and good for food’ (Genesis Chapter 1) meant those plants which grow wild, while the the Garden of Eden (as described in Genesis Chapter 2) might have contained only those plants that grow as a result of cultivation. Cultivated varieties of plants have existed since approximately 10,000 years ago the description of the Garden of Eden in Genesis took its final form approximately 2,500 years ago, when the distinction between wild and cultivated species was well known – though its scientific origin was of course unknown.

On the wider question, we should consider whether Adam and Eve were wrong to seek knowledge – and whether we are wrong to continue the quest. George Steiner wrote, in Bluebeard’s Castle, that ‘We cannot turn back. We cannot choose the dreams of unknowing. We shall, I expect, open the last door in the castle, even if it leads, perhaps because it leads, on to realities which are beyond the reach of human comprehension and control.’ He thought it possible that humanity is engaged on an endless quest for knowledge and that, as in Bluebeard’s Castle, opening the last door will lead to doom.

And is humanity descending ever-further into a morass of sin? I hope not – but Eve on the left (by Michaelangelo) does not look as though she has been leading the good life and Adam on the right looks emasculated as a result of eating too much factory-farmed chicken. I prefer the medieval Adam and Eve (from the Très riches heures) and believe that the planners and designers of more sustainable ways of living have much to learn from the middle ages and medieval gardens.

Category Archives: garden history

Bagh-e Fin garden in Iran – restoration and conservation plan

An interesting conservation resulted from shoving myself into the wall of a garden pavilion in order to take this photograph of the Bagh-e Fin garden in Kashan, Iran

When visiting the Bagh-e Fin, on 15th June 2004, one of the curators noticed me in a painful position outside his office. I was taking a photograph. He asked why I was doing it. I said I was interested in garden history. He asked if I thought the Bagh-e Fin was of equal historical importance to the great gardens of Europe. I said ‘Yes – probally more so, because it is the best surviving example of the world’s oldest garden design tradition, originating in the Fertile Crescent’. But, I said, it could be looked after even better than was then the case. ‘What should we do?’, he asked. I said I would make a proposal and send it to him. As we drove north into the desert, I sketched in the back of the car. A friend translated my comment into Farsi and we posted it to him. A reply is still awaited. In case the Bagh-e Fin Conservation Plan has been mislaid, it is now published it on the Gardenvisit website.

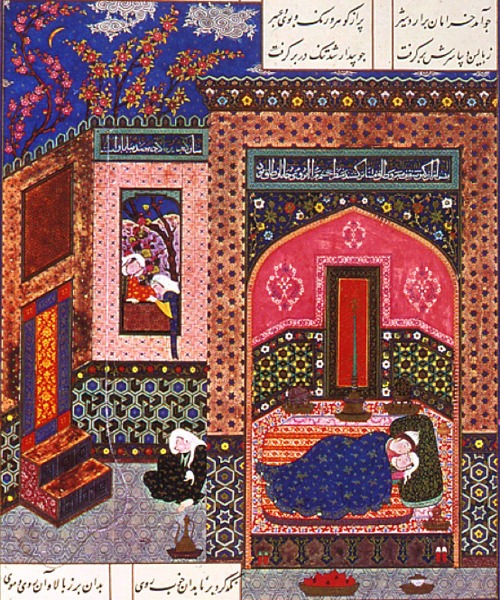

A Persian garden pavilion, with Ardashir and Gulnar

I wish Iran would devote less effort to enriching uranium and more to enriching Iranian gardens and conserving Persian gardens. Persia was one of the central powers in garden history, drawing upon and influencing Mesopotamia, Central Asia, India and Islam. My own modest proposal for conserving the Bagh-e Fin will be the subject of a future blog post.

Omar Khayyám (1048-1131), born in Nishapur, was an astronomer and a garden poet. The Rubiayat of Omar Khayyam, 1120 CE, begins:

I

Wake! For the Sun behind yon Eastern height

Has chased the Session of the Stars from Night;

And to the field of Heav’n ascending, strikes

The Sultan’s Turret with a Shaft of Light.

Awake Morning: For the sun behind yon eastern height.]

II

Before the phantom of False morning died,

Methought a Voice within the Tavern cried,

“When all the Temple is prepared within,

Why lags the drowsy Worshipper outside?”

III

And, as the Cock crew, those who stood before

The Tavern shouted – “Open then the Door!

You know how little while we have to stay,

And, once departed, may return no more.”

IV

Now the New Year reviving old Desires,

The thoughtful Soul to Solitude retires,

Where the White Hand of Moses on the Bough

Puts out, and Jesus from the Ground suspires.

V

Iram indeed is gone with all his Rose,

And Jamshyd’s Sev’n – ring’d Cup where no one knows;

But still a Ruby gushes from the Vine,

And many a Garden by the Water blows.

February in a medieval garden in France

Europe is still frozen but we should not complain – and perhaps our predecessors did not mind the cold either. This brilliant painting of a medieval garden yard is from Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry. The painting is dated to c1410 – so we can celebrate its 600th annniversary. The wattle fencing is exquisite. The sheep are better protected than on a modern farm. The beehives are in good order and produced a more nutritious sweetner than our refined and dangerous sugars. Mum is modest but the young girl and boy are exposing their genitals to the warmth of a fire. It reminds me of a lecture from the president of the students union in my first week at university. He solemnly informed his audience that if, before intercourse, a man spent an hour with his testicles between two lightbulbs it would reduce the risk of an unwanted pregnancy. I never put the theory to the test.

Europe is still frozen but we should not complain – and perhaps our predecessors did not mind the cold either. This brilliant painting of a medieval garden yard is from Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry. The painting is dated to c1410 – so we can celebrate its 600th annniversary. The wattle fencing is exquisite. The sheep are better protected than on a modern farm. The beehives are in good order and produced a more nutritious sweetner than our refined and dangerous sugars. Mum is modest but the young girl and boy are exposing their genitals to the warmth of a fire. It reminds me of a lecture from the president of the students union in my first week at university. He solemnly informed his audience that if, before intercourse, a man spent an hour with his testicles between two lightbulbs it would reduce the risk of an unwanted pregnancy. I never put the theory to the test.

St Anthony's Monastery, in Egypt, and the monastic gardening tradition

Saint Anthony (c 251–356) is known as ‘the Father of All Monks’. Athanasius wrote his biography and it spread monasticism in Western Europe. He was not the ‘first monk’ but he was a Christian ascetic who went into the wilderness. The present monastery was built (c 356) on his burial site and near his retreat. Its fortified character was a response to Bedouin attacks. St Anthony gave his father’s money to the poor and ‘shut himself up in a remote cell upon a mountain’ so that ‘filled with inward peace, simplicity and goodness’ he ‘cultivated and pruned a little garden’. Presumably, the garden was his food supply and the wilderness was the subject of his contemplation. This may well be the origin of a Christian approach to gardens, seeing them primarily as functional places – not as symbolic or luxurious places. Cloister garths belong to a different tradition: they are symbolic; they probably did not have a ‘use’; they became places of luxury. See posts on Certose Cloister, Canterbury Cloister, Salisbury Cloister and a hypothesis concerning the origin of Christian monasticism. Islam does not have a monastic tradition, though there are Dervish brotherhoods, possibly because the Arabs had sufficient experience of living in deserts.

(Image courtesy Miami Love)

Certose di Pavia Cloister Garden

The Carthusian Order was founded in the Chartreuse Mountains in the French Alps. ‘Charterhouse’ is the English name for a Carthusian monastery and ‘Certosa’ is the Italian name. Their motto is ‘ Stat crux dum volvitur orbis’ (‘The Cross is steady while the world is turning.’) A Charthouse was ‘a community of hermits’. Each member had his own cell and his own garden, in which to lead a simple life of work, prayer and gardening. But, like other monastic orders, there was a tendency for the order to turn, as the world changed, towards luxury. Simple cloister garths became richly ornamented gardens, as at the Certose di Pavia.

One could argue that the creation of beauty is a way of praising the Lord. But this does not accord with the founding principles of monasticism and one cannot imagine that St Anthony, St Benedict or St Bruno would have approved. Yet the world does change. So would anyone support a modern equivalent of a renaissance parterre at Salisbury Cathedral or Canterbury Cathedral or Westminster Abbey? A contemporary interpretation of an Italian cloister garden is planned next to St Andrew’s Cathedral in Glasgow.

(Image courtesy Kenya Allmond)