Dry stone walling is flexible; it does not use mortar; it is good for wildlife; it is a sustainable. The only minus points arise if fuel is used for quarrying and transporting the stone.

This video is of a Chelsea Fringe event in Crossbones Garden, near London Bridge Station. Participants receive a certificate of attendance at the end of the session. John Holt is a great teacher.

Category Archives: Garden Design

Review of the show gardens at the 2015 Chelsea Flower Show

Please see this page for video reviews of selected show gardens.

I’ve been too hot at Chelsea and I’ve been too cold. On Press Day, in 2015, I was too wet and too windswept. When the sun came out in the afternoon, the Press had to leave so that the Royal Family could enjoy the show. I’m not a republican, yet, but the rain did fall like stair rods. So what of the design quality of the Show Gardens? I thought some of the Fresh Gardens, on Royal Hospital Way, were better than most of the large gardens on the Main Avenue – some of which could be described as Stale Gardens.

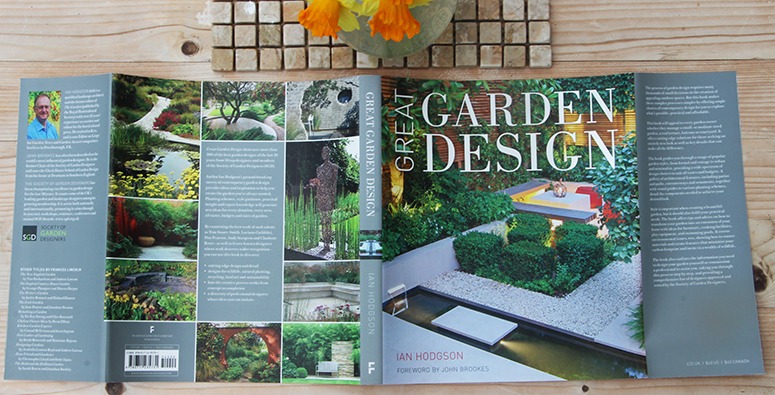

Great Garden Design by Ian Hodgson – review

The Society of Garden Designers has produced a very good book on garden design. I commend it to anyone commissioning a garden and to future historians of garden design.

The section I like best, on Outdoor Experiences, deserves to become a book in its own right. There are only four sections, on Relaxing, Dining, Playing and Bathing. But there are subsections, so that Dining includes Cooking Outside, Keeping Livestock and Growing Your Own.

This approach to garden design comes, in the UK, from John Brookes. His Room Outside, first published in 1969, launched British garden design on its profression from the Arts and Crafts Style to Modernism. In his introduction to Great garden design Brookes draws attention to the way in which ‘this book breaks down the overall plan of a garden and deals with the various sections and functions it may include’.

A failure to grasp the key principle of Modernism hindered, and hinders, the development of garden design. ‘Form follows function’ is the most convenient summary of Modern Movement principles but caused problems for garden designers. ‘What’ they wondered, ‘are the functions of a garden?’ My criticism of Great garden design is a weakness in the history and theory of garden design.

After Brookes’ Forward and an Introduction by Ian Hodgeson (the author) there is a chapter on Contemporary Garden Styles. A section on Sourcing Inspiration is followed by a section on Choosing a Style – which struck me as a return to the high Victorian eclecticism of Edward Kemp and the Mixed Style. It is followed by a menu of styles. Their names are Contemporary Formal, Urban Chic, Cottage and Country Style, Natural Style, Water Gardens and Subtropical Style. This is a departure from Modernism but I would not call it Postmodern and nor do I think the categories will be of use to those future garden historians who come across this useful and very well-illustrated book.

Great Garden Design was published 5th March 2015 by Frances Lincoln www.franceslincoln.com.

The Manali to Leh Highway & Landscape Change in Ladakh

Taking the footage for this video, in September 2014, was a good opportunity to reflect on landscape change in a hitherto remote region of India: Ladakh. There are many considerations:

- Ladakh was an important sector on the of the Silk Road Network, particularly for north-south trade and travel between India and China. The video uses quotations from European travelers who undertook the journey c1850-1950.

- Travel between Ladakh and Pakistan ended with the partition of India in 1947.

- Travel between Ladakh and China ended with the closure of the border, by China, in 1949.

- India responded by closing Ladakh to all travel and tourism

- From 1949 until 1974 Ladakh was cut off and isolated as rarely in its history

- Since 1974 Ladakh’s economy has become dependent on the army, which invests in roads. The military population of Ladakh is now greater than the civilian population but the army keeps its personnel largely separate from the local people.

- Ladakh’s other post-1974 economic prop is tourism. In summer there are more tourists than locals in the regional capital, Leh.

- Westerners, in the main, want Ladakh to remain an undeveloped and traditional region.

- Ladakhis, in the main, want to experience the ‘luxuries’ of western civilization.

So what should be done? I think Ladakh would have done better, if it could, to have followed the development path of Bhutan. This involves a very cautious approach to development and a concentration on the luxury end of the tourism market.

As things stand, the best approach is probably the adoption a forward-looking development policy as firmly rooted as possible in the principles of context-sensitivity and sustainability. This policy is exemplified by the Druk White Lotus School and its Dragon Garden.

Romesh Bhattacharji, an Indian who knows Ladakh very well, wrote in 2012 of the new roads which will open up Zanskar that ‘Many people, all outsiders typically, I have met, however, also moan about the loss of the traditional way of life of the people of Zanska. The latter want a better way of life than just being museum relics for tourists’ It is a well-aimed criticism. But ‘traditional’ and ‘development’ need not be in opposition: a Middle Way is also possible, by design. The Druk School and Dragon Garden make a cameo appearance on the above video and are explained in more detail by the videos on the DWLS Dragon Garden Playlist.

Cycle infrastructure expenditure in the UK and Holland

- The UK spends £2/person/year on cycling

- Holland spends £24/person/year.

- So Holland has better cycling infrastructure.

- The Dutch spend ten times as much on cycling as the British and they have ten times as many urban journeys/person (30%+ vs 3%+)

- It figures

To make up for years of neglect, the UK should spend £50/person/year on cycling. When UK cycling infrastructure is as good as Holland’s, this can drop back to £25/year.

Just think, about this quotation from a Sky report on The British Cycling Economy.

The proportion of GDP spent on public infrastructure by the UK Government has been lower than government spending in many other countries, averaging around 1.5 per cent between 2000–2004 – around half of the investment occurring by governments in Italy and France. Despite rail accounting for only six per cent of total passengers in the UK, the sector received a subsidy of around £6.5b, almost equalling road investment, which carries the majority of journeys undertaken in the country. In addition, tax revenues from transport eclipse expenditure on transport by £14b, reflecting a net flow out of the sector from receipts. Cycling’s proportion of the UK transport budget is less than one per cent, whilst in the City of London, one of the UK’s larger cycling ‘hot spots’, cycling has been apportioned 0.45 per cent of the £135m transport budget, amounting to around £600,000.54 Currently, 10,000–15,000 cyclists commute into the Capital each day, which has increased by 52 per cent since 2007, and is forecast to quadruple by 2025.55 These macro and micro conditions continue to create the ideal milieu for cycling participation to increase across social strata, with significant benefits.

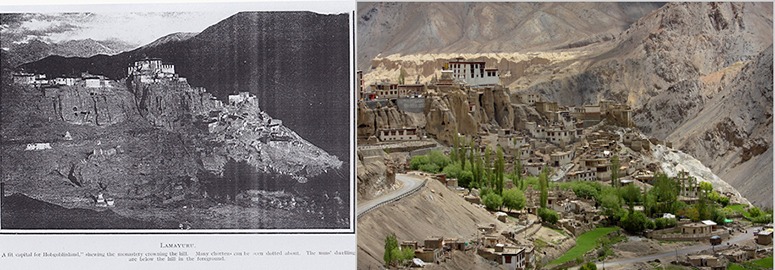

Lamayuru, Ladakh, social, agricultural and urban change 1926 – 2010

– the town’s population is growing

– traditional architecture is still favoured, but new roads and telephone poles have an ‘anywhere’ quality (they are built and funded by the Indian army)

– Lamayuru is popular with tourists, despite its remoteness

– the expansion, so far, has been on stony ground

– there is a danger of Lamayuru expanding onto its very scarce resource of agricultural land (but there is also a danger of the land being neglected, because it is cheaper to import food from other parts of India)

– either there are more poplar trees or they are being allowed to grow taller for amenity reasons

– the ‘agriculture’ in old Ladakh is closer to what we would call horticulture than to what we call agriculture but if you call the cultivated areas ‘gardens’ it must be noted that their use is to grow food plants rather than ornamental plants.

Dr Adolph Reeve Herber, who took the black and white photo was an English doctor and missionary. He and his wife were based at the Moravian School in Leh from 1912-25. The mission ran a school, which survives, but did not have much success in converting the Ladakhis to Moravian protestantism. Nor did Dr Herber find much demand for his medical skill – because the local people were so healthy. He therefore had time to study other aspects of Ladakh’s culture and environment, including its flowers: ‘At the foot of the high Kardong Pass behind Leh… to mention a few only, are found yellow Iceland poppies, Michaelmas daisies, small deep-blue gentians, forget-me-nots, forming a carpet of blue on the Zogi [Zoji-La] stretches, but replaced by the deep blue of the borage below the Kardong, deep purple orchids, primulas in all shades of magenta and purple, cow parsley, a kind of stinging nettle, asters, saxifrage, vetches, Canterbury bells, and on the Zogi the single anemone and the tall bunched Japanese variety, even the green foxglove and the coarse edelweiss.’