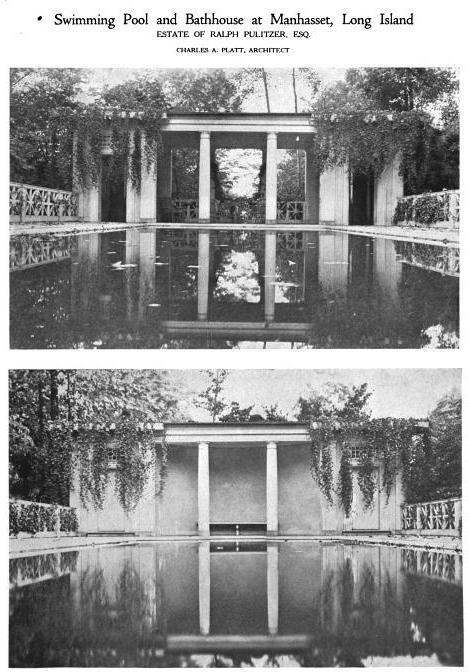

River Park in Zhangjiawo New Town

中国城市化进程中的整体城市水管理:张家窝新城设计—Dreiseitl工作室 Thinking about the urban development which has taken place in mainland China since Deng Xiaoping repudiated the Cultural Revolution in 1977, the words which come to mind are: fantastic, astonishing, unbelievable and unprecedented. If, however, a laowai 老外 may be allowed a word or two of criticism (1) the work has been a little rushed (2) too few landscape architects were involved in the urban design (3) it is a pity that so much was learned from America in comparison with what was learned from Europe (4) nature in general and water in particular have suffered from the urbanisation (5) the work could have been done in a more Daoist way than it has been, with the reverence for nature which was traditional in Daoist and Buddhist culture.

With these thoughts in mind I was very pleased to read that Atelier Dreiseitl have completed a project in Zhangjiawo New Town. As noted in a review of Dreiseitl’s book on Recent Waterscapes, his work has the virtue which Lewis Mumford attributed to Ian McHarg of combining ‘scientific insight’ with ‘constructive environmental design’.

‘The Chinese seem to have been the first to perceive the relationships joining the flow of water with the shape of land and with the social and philosophical milieu.According to Joseph Needham, China produced two opposing schools of thought in hydrological engineering as in virtually ever other area of human endeavor: the Confucian and the Taoist. The Confucians were disciplinarians who believed in strict rules and strong measures of control. They advocated ‘high and mighty dykes, set nearer together’… The Taoists, or expansionists, were more inclined to let water take its own course as far as possible, giving it plenty of room to spread. The result was a very complex network of flow. An early Taoist engineer, one Chia Jang, wrote over 3000 years ago that ‘those who are good at controlling water give it the best opportunities to flow away; those who are good at controlling the people give them plent of chance to talk’ (John Tillman Lyle, Design for human ecosystems: landscape, land use, and natural resources (1999, p.236)

The American approach to water management was Confucian, in the sense of regulatory. But McHarg introduced a more Daoist approach in the famous project for Woodlands, Texas. It proved to be more beautiful, more effective and more ecological. And it came in at 25% of the cost of the US engineers ‘Confucian’ system. As McHarg observed ‘there is no better union than virtue and profit’. I therefore hope Dreiseitl is re-pioneering a Daoist approach to holistic urban water management in the formerly Daoist Middle Kingdom. Continental European cities, because so many of them were founded in the Middle Ages, have a long tradition of incorporating open water channels within the fabric of the city. American cities, because so many of them date from the nineteenth century, have tended to put as much urban water as possible into underground pipes. China seems to have done things the American way, so far.

Images courtesy Tian Yuan

Brochs are a unique building form, dating from the 1st century BC and indigenous to Scotland. They had internal wooden floors and they were inhabited. This is clear. But how they were located and why they were built is unclear. Gordon Childe interpreted brochs as fortifications from which chiefs ruled subject populations. Since no evidence for this could be found, this was followed (in the 1980s) by a theory that they were prestige dwellings for important families, but again there was a lack of evidence and it is often the case that brochs are not located in good agricultural land. But many brochs do have significant positions in the landscape, near cliffs, in valleys and by narrow stretches of water. This suggests, to me, that like so-called hill-forts and stone circles, they had a symbolic and aesthetic role in proclaiming that an area of land was in the ownership of a clan of closely related families. Brochs are early examples of Scottish landscape architecture.

Brochs are a unique building form, dating from the 1st century BC and indigenous to Scotland. They had internal wooden floors and they were inhabited. This is clear. But how they were located and why they were built is unclear. Gordon Childe interpreted brochs as fortifications from which chiefs ruled subject populations. Since no evidence for this could be found, this was followed (in the 1980s) by a theory that they were prestige dwellings for important families, but again there was a lack of evidence and it is often the case that brochs are not located in good agricultural land. But many brochs do have significant positions in the landscape, near cliffs, in valleys and by narrow stretches of water. This suggests, to me, that like so-called hill-forts and stone circles, they had a symbolic and aesthetic role in proclaiming that an area of land was in the ownership of a clan of closely related families. Brochs are early examples of Scottish landscape architecture.