Should Ladakh be modernised? Can it be avoided? Anyone travelling to Kargil or Leh via the Zoji La must think ‘This CANNOT be the main road to Ladakh’, ‘It is inconceivable that most of the country’s fuel and construction materials are carried in on this road?’ ‘Surely it can’t be closed for six months/year?’ ‘Why in heaven’s name haven’t they built a tunnel’, ‘Is this country run by 3 idiots?’. But anyone who reads Helena Norberg-Hodge’s Ancient Futures: Learning from Ladakh may conclude ‘Please God, don’t let them build a new road over the Zoji-La’. She argues that ‘development’ is spoiling Ladakh. The men are giving up farming to become taxi drivers. The women, who lived in rural bliss in wonderful communities, are now finding themselves isolated in ugly modern flats with their husbands doing urban jobs, their young children in schools and their older children hanging about on street corners, taking drugs and thinking about motorbikes and larceny.

Though my sympathies lie with Helena Norberg-Hodge, I don’t know who is right. But I do know that work on an all-weather Zoji La Tunnel is scheduled to begin in 2012. Should it happen, the above video will be a visual record of the pass in July 2012. The longest delay was on a good section of road, just below the pass, near the turn-off to Amarnath (see photos), a stalagmite worshipped by Hindus as the phallus of Lord Shiva – which has melted because growing numbers of devotees are generating too much body heat. The number of pilgrims on the Amarnath Yatra has risen exponentially over the last decade. Almost 100 of them died this year and over 40,000 received medical treatment. They sleep in the largest camp site I have ever seen (which can be glimpsed on the video). I was travelling to the Druk White Lotus School and thinking about how it could have a Dragon Garden to go with its mandala plan. A landslide closed the road for a while, as though a local dragon had stirred.

Helena Norberg-Hodge Ladakh video Part 1

Helena Norberg-Hodge Ladakh video Part 2

Helena Norberg-Hodge Ladakh video Part 3

Category Archives: Asian gardens and landscapes

DWLS Dragon Garden in Shey, Ladakh, for the Druk White Lotus School

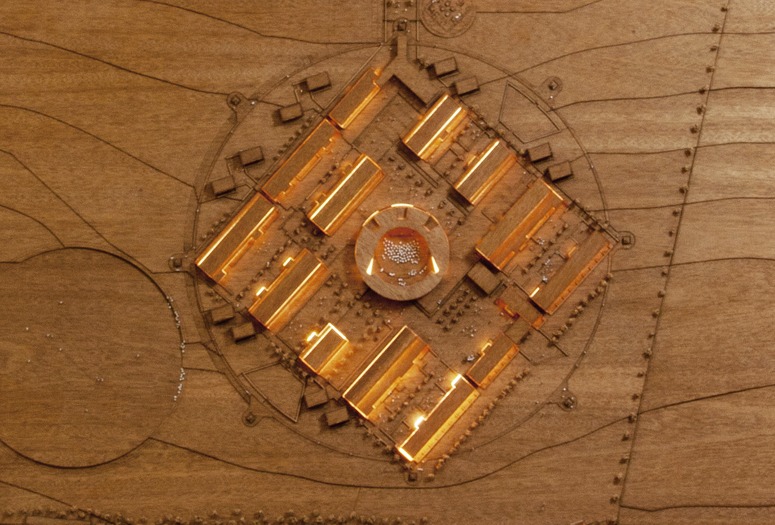

The architectural layout of the Druk White Lotus School, designed by Arup Associates, is based on a mandala. In the Sanskrit of the Rig Veda, the sections were called mandalas, meaning ‘cycles’ or ‘chapters’, rather as TS Eliot divided his Four Quartets into sections. The Rig Veda poems are often described as hymns and were receited by nomads on ritual occasions. When the nomads became settlers special places, including temples, were designed for rituals and they too became known as mandalas. Hindu and Buddhist sacred places, including stupas, are therefore said to have a mandala plan. In Tibetan and Ladakhi culture, which are Vajrayana Buddhist, a mandala is interpreted as a diagram which represents the geography of the cosmos.

The Druk White Lotus School (DWLS) was built in the desert outside Shey, the former capital of Ladakh. The buildings are nearing completion in 2012 and the next stage is to convert the school surroundings from desert to garden and landscape. Since the school was made under the auspices of the Drukpa Lineage, making a ‘Dragon Garden’ is appropriate. ‘Druk’ means ‘Dragon’ and ‘Druk-pa’ means ‘Dragon-person’, with the Lineage led by the Gyalwang Drukpa. What form a ‘Dragon Garden’ might have is yet to be determined.

The above video shows a school ritual (a morning assembly) taking place in a Dharma Wheel at the centre of the DWLS Mandala. Note that the children sitting beside the monk are using their hands to form the mudras. My impression is of kindly, enthusiastic and warm-hearted children – and I wish I had a similar impression when looking at school children in london.

Mandalas can take many forms and can be made in many ways. The below image shows coloured sands used to make a sand mandala.

A model of the mandala section of the plan for the Druk White Lotus School, by Arup Associates.

Was the Aral Sea one of 'nature's mistakes', or was it the scene of an environmental crime?

The left photo shows, I think, the Aral Sea as it was last week. Wiki reports that ‘Soviet experts apparently considered the Aral to be “nature’s error”… [So] ‘From 1960 to 1998, the sea’s surface area shrank by approximately 60%, and its volume by 80%. In 1960, the Aral Sea had been the world’s fourth-largest lake, with an area of approximately 68,000 square kilometres (26,000 sq mi) and a volume of 1,100 cubic kilometres (260 cu mi); by 1998, it had dropped to 28,687 square kilometres (11,076 sq mi), and eighth-largest. The amount of water it had lost is the equivalent of completely draining Lake Erie and Lake Ontario. Over the same time period, its salinity increased from about 10 g/L to about 45 g/L’. Which view is correct? The lives of those who won their living from the Aral Sea have been devastated. But the population of Uzbekistan benefits from valuable exports of cotton.

The left photo shows, I think, the Aral Sea as it was last week. Wiki reports that ‘Soviet experts apparently considered the Aral to be “nature’s error”… [So] ‘From 1960 to 1998, the sea’s surface area shrank by approximately 60%, and its volume by 80%. In 1960, the Aral Sea had been the world’s fourth-largest lake, with an area of approximately 68,000 square kilometres (26,000 sq mi) and a volume of 1,100 cubic kilometres (260 cu mi); by 1998, it had dropped to 28,687 square kilometres (11,076 sq mi), and eighth-largest. The amount of water it had lost is the equivalent of completely draining Lake Erie and Lake Ontario. Over the same time period, its salinity increased from about 10 g/L to about 45 g/L’. Which view is correct? The lives of those who won their living from the Aral Sea have been devastated. But the population of Uzbekistan benefits from valuable exports of cotton.

PS I wish Google Maps was available on aircraft, so that passengers know their exact position in relation to the ground.

The placement of Buddhist stupas as landscape architecture

Having wondered for some time whether the design and siting of the pyramids at Giza was conceived as a ‘stylization’ of sand dunes on the boundary between the Red Land (desert) and the Black Land (farmed land), I timidly kept the idea to myself until Charles Jencks put forward the same idea. Now I wonder if the largest stupa field in Ladakh (above, at Shey) was conceived as a stylization of a mountain range. The stupas have this appearance but there are many considerations:

Having wondered for some time whether the design and siting of the pyramids at Giza was conceived as a ‘stylization’ of sand dunes on the boundary between the Red Land (desert) and the Black Land (farmed land), I timidly kept the idea to myself until Charles Jencks put forward the same idea. Now I wonder if the largest stupa field in Ladakh (above, at Shey) was conceived as a stylization of a mountain range. The stupas have this appearance but there are many considerations:

- Hindu gods are associated with mountains

- Buddhism does not have creator gods but draws much from Hindus ideas

- Stupas are symbols of the Buddha’s presence

- Nirvana is represented in Buddhist art as being in a mountainous region

- Mt Kailash is sacred to Hindus and Buddhists

An interesting aspect of Ladakh is that it has no tradition of making ‘pleasure gardens’ but the whole country appears to have been conceived as a garden.

The Buddhist cave at Phuktal Gompa (Phugtal Monastery)

The great cave of Phuktal Gompa in Ladakh has a sacred spring within. The monastery is said to have been built here because there was a forest on the slopes above, from which a lone tree survives. The cave is supposed to house the spirit of the first guru, Rimpoche.

Caves have a special place in Buddhism, because wandering monks used them for prayer, meditation and rest, and Ngawang Tsering (1717-94) wrote that: ‘Nurtured as sons of mountain solitude they dressed in clouds and mist and wore as hats deserted caves. Totally unconcerned with the world’s ways and mundane happiness they contemplated impermanence to create a sense of urgency and thus to make the best use of their life time. Meditation on the ominpresence of death served as a pillow and they wrapped themselves up in the cloth of mindfulness of karma. The mats which they spread were their awareness of the disadvantages of samsara which they likened to a whirlpool or a tapering flame. I sing my songs to induce kings to rule with the ten virtues, for the sake of the lowly so that each according to his capacity may rejoice in the Dharma, for the sake of the teachers pointing them to tantras, sutras and teachings, for the sake of earnest meditators that they may realise equanimity and insight, for the sake of the yogins with clear perception that they may be endowed with supreme vision action and function’

Image courtesy Kateharris

What are the conditions for good urban landscape design?

Edmund Bacon, in his 1974 book on Design of Cities, interpreted Rome's spatial plan in essentially geometrical terms (an axial movement system). Historically, it was created WITH temporal and spiritual power to symbolise these qualities. Are they still the necessary conditions for good urban design? No living planner or designer has the 'powers' of Sixtus V and Urban VIII. Is this why we are making such disappointing cities?

What are the social, political and economic conditions in which urban landscape design is most likely to flourish? I very much hope my answer to this question is wrong, but here goes: “in cities where an enlightened king was guided by spiritual beliefs”. Why should this be so? (1) Without temporal power, urban design is scarcely possible. (2) without spiritual power, objectives are likely to be short term and non-idealistic (3) short-term commercial and military objectives benefit rulers and disadvantage peoples. As Alexander Solzhenitsyn observed “Is it not true that professional politicians are boils on the neck of society that prevent it from turning its head and moving its arms?”. “It is not victory that is precious but defeat. Victories are good for governments, whereas defeats are good for the people. After a victory, new victories are sought, while after a defeat one longs for freedom, and usually attains it. Nations need defeats just as individuals need suffering and misfortunes, which deepen the inner life and elevate the spirit.” The great urban designs were made in periods of faith and monarchy Beijing from 1293-1912, in Isfahan under Shah Jehan, in Rome under the Popes and in Paris under the kings and emperors. What comparable successes can be claimed by the faithless democracies and autocracies of the twentieth century? The great powers of the modern world suffer from not having been defeated in great wars.

Image courtesy RTSS