An international Web 2.0 design competition for Tiananmen Square was announced in March 2009. The winners are listed below. A full .pdf report on the Tiananmen competition is available for free download from the Gardenvisit.com Website. All the Tiananmen entries can be seen on Flickr. The 3 judges, listed below, thank everyone who took part.

• Christine Storry (Australia): architect and urban designer

• Tom Turner (UK): landscape architect and town planner

• Xiru Zhao (China): architect

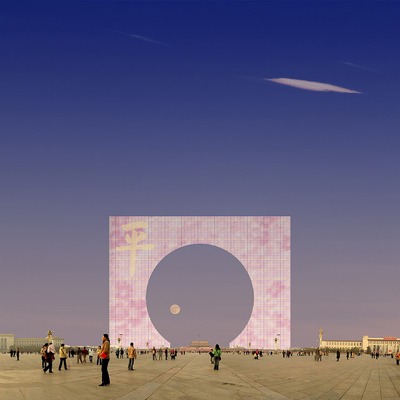

First prize: Thunsdorff

Thunsdorff, Ueli Mueller Landscape Design, Kleinertstrasse 3, 8037 Zurich, Switzerland, mail @ uelimueller.ch, www.uelimueller.ch

The Thunsdorff design is visually strong, deceptively simple and a complex response to the site. A Moon Gate has historic, symbolic and garden interest. The people’s encyclopedia (Wikipedia) states that:

A Moon Gate (Chinese: 月亮门; pinyin: yuèliàng mén) is a circular opening in a garden wall that acts as a pedestrian passageway, and a traditional architectural element in Chinese gardens. Moon Gates have many different spiritual meanings for every piece of tile on the gate and on the shape of it. The sloping roofs of the gate represent the half moon of the Chinese Summers and the tips of the tiles of the roof have talisman on the ends of them…. The purpose of these gates is to serve as a very inviting entrance into gardens of the rich upper class in China. The gates were originally only found in the gardens of wealthy Chinese nobles.

The Chinese word for round (圆,yuan) has the same pronunciation as the Chinese word for ‘garden’ (园,yuan). Another meaning of ‘yuan’ in Chinese is ‘perfect’ (圆满)- which is a symbol representing the owner of a garden who wishes to conduct himself perfectly and work smoothly. The placement of the Moon Gate in Tiananmen Square creates two spaces with a pedestrian link and, alluding to them as two different gardens. There could be problems for traffic on Changan Street and obstruction of the visual axis from the Tiananmen Gate. A vehicular underpass would also be possible. The great Moon Gate can symbolise the ancient desire for Harmony and Unity – and the fact that modern China belongs to all of its people and no longer to a rich upper class. Thunsdorff explains the design in thirty words:

China – Country of grand spirit -The world’s largest square shall remain an open space – We suggest a new perspective link between past and present pointing to the future – Heavenly Peace

There may be something of Confucius in this (‘Study the past if you would define the future’) and also something of Chairman Mao (‘Such is history, such is the history of civilization for thousands of years’). The idea of a sublime symbol soaring above the commercialism of modern Beijing is attractive, with something of a parallel in the Parisian Grande Arche. The comparison between the Ming dynasty axis in Beijing and the Louvre-Defense axis in Paris is interesting – and both can be carried into the future as examples of how city form can be conserved and extended. They support the view that 600 years is a good timescale for city planning: one should look back at least 300 years and look forward at least for another 300 years.

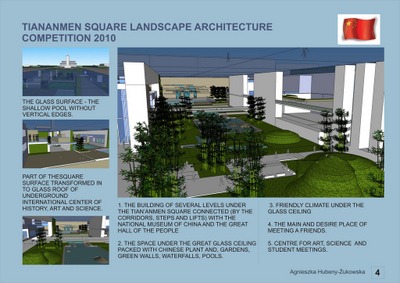

Second Prize Aga H

Aga H Agnieszka Hubeny-Zukowska, Pracownia Sztuki Ogrodowej, 80-360 Gdańsk Ul.Krzywoustego 5A/5, Poland, Tel./fax: +48 (58) 511-04-69 www.pracowniasztukiogrodowej.pl biuro [@] pracowniasztukiogrodowej.pl

The Aga H design proposes a context-sensitive underground design which retains the integrity of Tiananmen Square as a huge and yet balanced space. The underground ‘garden world’ also responds to the context of a climate which is too hot in summer and too cold in winter. Aga H sees great value in traditional Chinese design but, as a world city, argues that Beijing can also symbolise a modern approach to design. To leave space for great events and to avoid competition with older buildings, the surface level therefore remains ’empty’. At ground level the main change would be two great blocks of pleached trees with seating beneath. They would flank the Monument to the People’s Heroes and the Mausoleum of Mao Zedong. A glass-roofed space beneath Tiananmen Square would contain a garden world and a Center for History, Art and Science. There would be underground links to the National Museum of China and the Great Hall of the People.

Third Prize: Whitney Hedges

Whitney Hedges, garden designer and landscape architect, England, www.whitneyhedges.co.uk polkadotplants @ googlemail.com

Only eighteen words of explanation were given (‘One Light: Strong lights projecting upwards, set flush into paving. Commemorating those who fell in the 1989 demonstrations’) but more points arose in an online discussion: ‘I like Whitney Hedges design very much… it is sensitive to all the considerations for this site and yet is quite a dramatic statement of the individuals heroic messages’. ‘One could also say that it links Earth to Heaven, which was the traditional role of Chinese Emperors (they were Sons of Heaven)’. ‘ I’m not sure that mixing these images of the Speer’s “Cathedral of Light” at the Nuremberg Rally with the image of the Tiananmen Square is a very good idea’. The reference to Speer is both interesting and troubling.