Lewis Mumford, in his introduction to Ian McHarg‘s Design with Nature, wrote that ‘It is in this mixture of scientific insight and constructive environmental design, that this book makes its unique contribution’. It was a perceptive remark and I would like to pay a similar comment to the books which Herbert Dreiseitl has published with the title Waterscapes: Herbert Dreiseitl combines scientific insight with an ethical concern for sustainability and an enthusiasm for artistic creation. See Herbert Dreiseitl biography & cv. Waterscapes is already on our list of 100 best books on landscape architecture and in 2009 Dreiseitl published Recent Waterscapes.

Dreiseitl has the scientific insight to understand the water cycle and the negative impacts upon it from poorly conceived urbanisation. He also practices constructive environmental design and he makes a unique contribution. Landscape architecture would be a far stronger profession if more designers were able, simultaneously, to make the world more sustainable and more beautiful. But is it art? and, indeed, What is art? Leo Tolstoy asked this question and, in the Wiki summary: ‘According to Tolstoy, art must create a specific emotional link between artist and audience, one that “infects” the viewer.’ The Wiki entry on Art, begins as follows: ‘Art is the product or process of deliberately arranging symbolic elements in a way that influences and affects the senses, emotions, and/or intellect. It encompasses a diverse range of human activities, creations, and modes of expression, including music, literature, film, photography, sculpture, and paintings.’ I think Dreiseitl passes these tests but I also remember Tracey Emin‘s declaration that one of her works was art ‘because I say it is art’. Dreiseitl could pass this test – and I think he should have a go at it, with a better explanation than Emin. He could say that he has analysed the nature of the world’s watery aspect and found a way of expressing his view in a 3-dimensional and visually dramatic way which depends upon the exercise of hard-won skills. His water sculptures are made in a studio at a 1:1 scale and then cut in granite. Similarly, Rodin worked in clay and had his sculptures cut in marble or cast in bronze. Rodin’s interest was sex; Drieseitl’s is also concerned with the future of life on earth. But my account of his work will not do: Dreiseitl needs to pen an account of ‘why I am an artist’ – and he should exhibit sculptural work in galleries so that it appears in catalogues and passes the commercial test for a work of art.

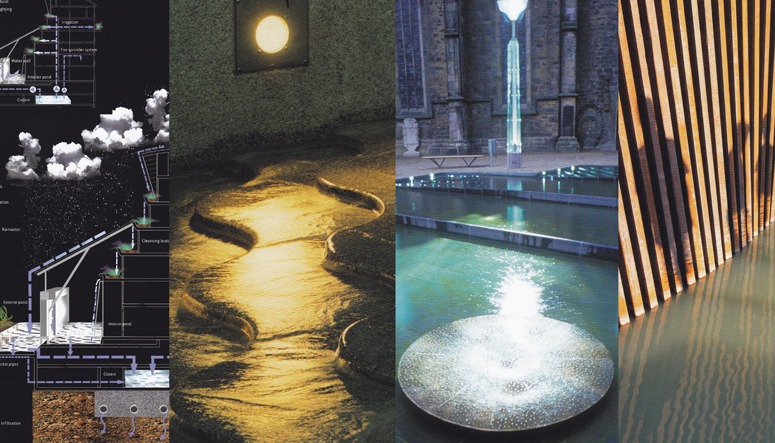

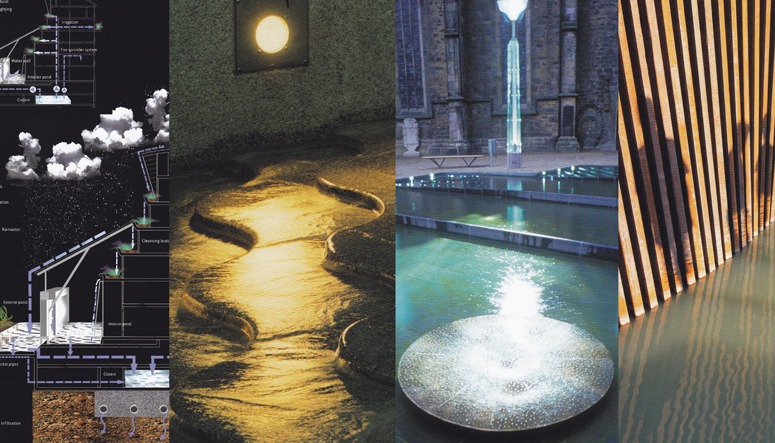

My favourite projects from Herbert Dreiseitl’s Recent Waterscapes, from left to right, below are:

The Nuremberg Prisma, Hannoversch Munden, Town Square in Gummersbach, Tanner Springs Park in Portland,

There is one problem with Dreiseitl’s projects: the vegetation is often managed on a habitat-creation basis and this tends to look ragged in the early years. In the fullness of time, they may well become beautiful semi-natural habitats. But one wonders if there is a way of making them more beautiful in the early years. The example below is a rainwater retention scheme on the Kronsberg in Hanover, Germany.