A previous post considered landscape urbanism and led to this definition:

LANDSCAPE URBANISM is an approach to urban design in which the elements of cities (water, landform, vegetation, vertical structures and horizontal structures) are composed (visually, functionally and technically) with regard to human use and the landscape context.

I am content with this definition for the time being but would like to give a little more explanation.

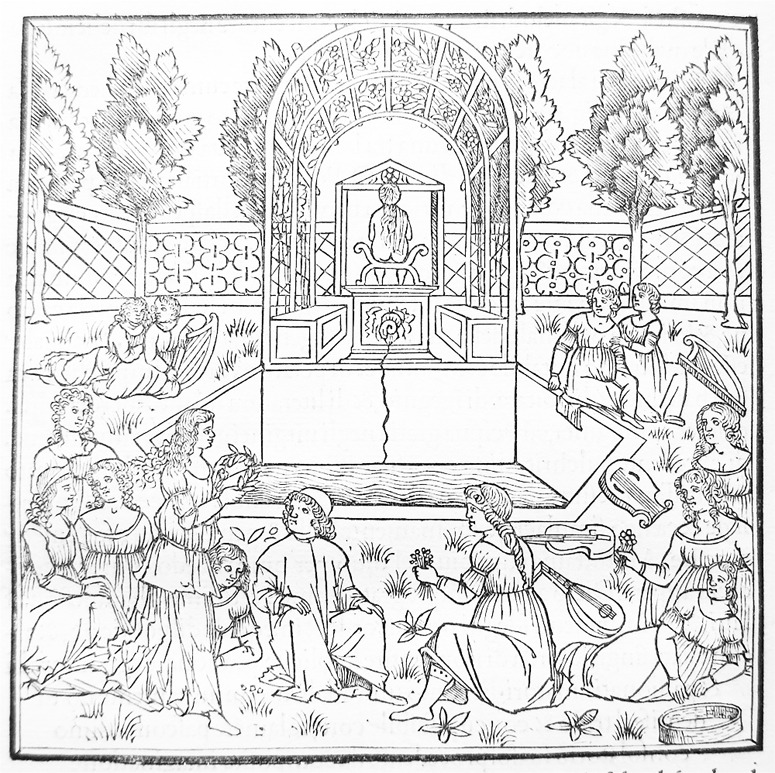

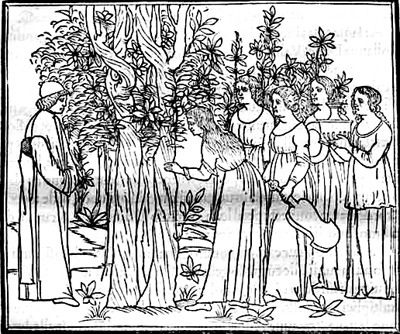

(1) The idea of ‘compositional elements’ comes from the history of garden design. It is a field in which water, landform, vegetation, buildings and paving have been composed, for at least 5,000 years – and it has always been done with regard to exiting landscapes and specific human uses. This has often made garden design a crucible for urban design, with the famous examples of Late-Renaissance Rome, Safavid Isfahan, Yuan and Ming Beijing, Georgian London, Late-Baroque Paris, even-later Baroque Washington DC and the Garden Cities of the twentieth century.

(2) The classification of design objectives (functional, technical, visual) is based on Vitruvius: Commodity, Firmness and Delight.

Under landscape urbanist programming, the design of urban space begins with the design of urban space. Buildings are then arranged and designed to surround and contain the urban space. Designing the buildings before the space will almost always diminish the potential quality of the urban space: visually, socially and ecologically.

Above image courtesy François Bouchet