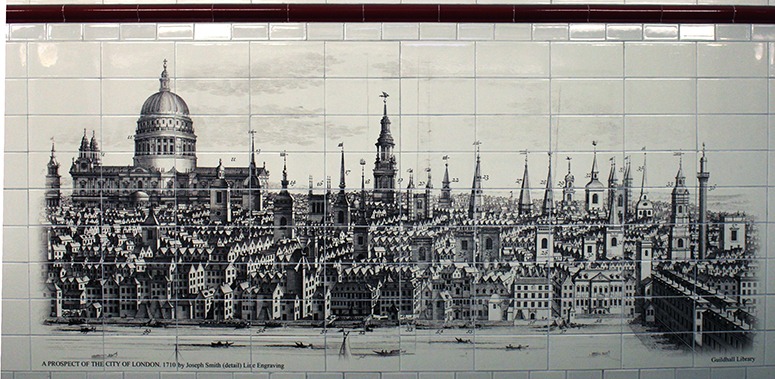

I see the Banks of the Thames as a place where, during the twentieth century, unimaginative planning and selfishly mediocre architecture often conspired to produce designs better suited to a rundown provincial town than to the heart of a great city. Skylines, landscape and architecture should be considered together, looking to the past and looking to the future. ‘Protecting’ views is important but insufficient. Proposals for ‘high buildings’ ‘tall buildings’ and ‘towers’ should be viewed in context, never in isolation. Studies of their visual and environmental impact require scenic quality assessments, a policy context and full testing on a digital model of the city. As the below quotations reveal, London’s river is both a Place of Darkness and a Place of Light.

William Blake, in 1794, found ‘in every face I meet / Marks of weakness, marks of woe’ where ‘the Thames does flow’.

William Wordsworth, 8 years later found the Thames a river of beauty and romance. He declared that ‘Earth has not anything to show more fair’ (1802).

Joseph Conrad, in 1899, knew the Thames as a place of history, romance, toil, darkness and light. He saw London as ‘the biggest, and the greatest, town on earth’, a place which had known ‘the dreams of men, the seed of commonwealths, the germs of empires’ and was yet ‘one of the dark places of the earth.’

Since 1945 property developers have seen the Thames as a place to make a quick buck

Since 2000, some wealthy immigrants have viewed riverside apartments as great places to launder the ill-gotten gains of financial scams and miscellaneous corruption.

Recent blog posts about London’s River Thames skyline landscape

- The 122 Leadenhall Cheesegrater and protecting London’s skyline landscape view of St Paul’s Cathedral from Fleet Street

- The Shard architecture and skyline landscape symbolic reviews

- Sunlight, tall buildings and the City of London’s new urban landscape architecture

- The visual impact of Renzo Piano’s Shard on the landscape and skyline of the River Thames

- London’s skyline: landscape and high buildings policy – and my apology for postmodern urban design

- London Sightseeing – a cruise on a River Thames boat

See also: Rem Koolhaas on London’s skyline. Koolhaas remarks that ‘London has always changed dramatically and it’s still is not a very dramatic city. So it can go on. I think that in London whatever you do you do not disturb an earlier coherence. You do not disturb an earlier utopia like in Paris. It can stand a lot of development without suffering’. I read this comment as a polite way of saying that most of London’s riverside is pretty dull, as the above video shows, it has its moments – but not enough of them.