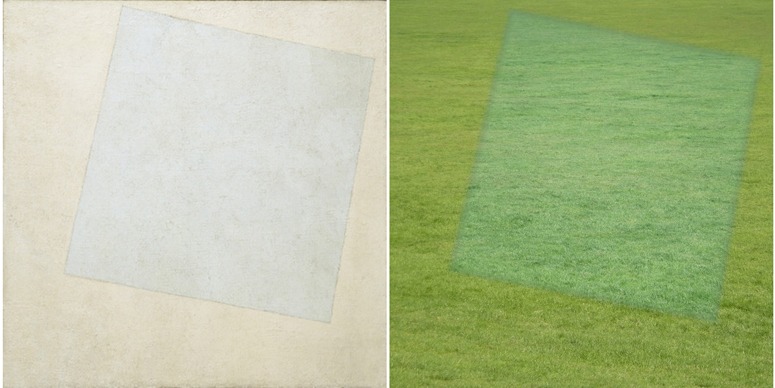

With the creditable exception of Burle Marx, and perhaps James Corner, landscape architects have been slow in responding to Suprematicism. Kasimir Malevich used this term as an alternative to Non-objective Art, which is itself an alternative to the more common Abstract Art. Malevich was thinking of its supremacy over previous art movements. Part of Malevich’s inspiration, like Corner’s, was from aerial photography: he abstracted patterns from landscapes. His suprematist ‘grammar’ was based on the elemental geometric forms, particularly the square and the circle. In the Eastern Orthodox tradition the holy family were believed to have a presence in icons. Comparably, a square is a square: it is not a picture of a square. This gives non-objective art a supremacy over representational (objective) art. Landscape architecture shares this type of supremacy over landscape painting: it is about making real places, not pictures of places. But landscape architects should also be fine artists in the sense of expressing truths about the nature of the world. Green-on-Green abstracts a truth about humanity’s relationship with the natural world: the works of man are always part of nature and always distinguishable from nature. We can guess that the term Abstract Art did not appeal to Malevich because of its use to mean ‘abstracted from the external world’. Malevich believed that art is spiritual. One can however, imagine that Malevich would have been happy to describe the ‘other’ type as Concrete Art, using concrete in the logician’s sense as an opposite to abstract.

With the creditable exception of Burle Marx, and perhaps James Corner, landscape architects have been slow in responding to Suprematicism. Kasimir Malevich used this term as an alternative to Non-objective Art, which is itself an alternative to the more common Abstract Art. Malevich was thinking of its supremacy over previous art movements. Part of Malevich’s inspiration, like Corner’s, was from aerial photography: he abstracted patterns from landscapes. His suprematist ‘grammar’ was based on the elemental geometric forms, particularly the square and the circle. In the Eastern Orthodox tradition the holy family were believed to have a presence in icons. Comparably, a square is a square: it is not a picture of a square. This gives non-objective art a supremacy over representational (objective) art. Landscape architecture shares this type of supremacy over landscape painting: it is about making real places, not pictures of places. But landscape architects should also be fine artists in the sense of expressing truths about the nature of the world. Green-on-Green abstracts a truth about humanity’s relationship with the natural world: the works of man are always part of nature and always distinguishable from nature. We can guess that the term Abstract Art did not appeal to Malevich because of its use to mean ‘abstracted from the external world’. Malevich believed that art is spiritual. One can however, imagine that Malevich would have been happy to describe the ‘other’ type as Concrete Art, using concrete in the logician’s sense as an opposite to abstract.

The pictorial space of Surpemist art had to be “emptied of all symbolic content and all content signifying form.” It was supposed to show a new reality where thought was of primary importance.

Yet it was Malevich’s belief that Suprematist art would be superior to all the art of the past, and that it would lead to the “supremacy of pure feeling or perception in the pictorial arts.”

He was intrigued by the search for art’s barest essentials.

Echoes of Suprematism are said to be present in the work of Zaha Hadid. [ http://www.zaha-hadid.com/exhibitions/zaha-hadid-and-suprematism ]. The work is strongly exploratory in an architectonic sense. It is both elemental and relational.

Princeton’s seminar on the Architectonics of nature assist in understanding what this might mean for landscape architecture.[ http://www.princeton.edu/~freshman/ ]

The objective of creating “pure feeling or perception in the pictorial arts” is peculiarly appropriate for garden and landscape design. In the early days of modernist gardens (say 1920-1950) designers had a sense that garden and landscape design ‘ought’ to be modern but that somehow it was not possible. Two of the difficulties were (1) such modernist materials as glass and concrete did not, at first, seem to have much of a place in gardens (2) designers were hazy about what the ‘functions’ of a garden might be. This should have left them free for Suprematist experiments in ‘pure feeling’ – but it is hard to find examples. My explanation is that garden and landscape designers were insufficiently interested in ‘pure theory’. They were practical men and practical women.

It is significant that Zaha Hadid spent many years on theoretical projects before she became involved with practical projects, as did the Russia’s avant garde artists.

Yes, the applications are not obvious, but it is interesting to see what Dan Kiley achieved in this context.

[ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Jefferson_National_Expansion_Memorial_grounds_-_Dan_Kiley_landscape_designer.JPG ] and [ http://farm3.static.flickr.com/2478/3566610021_84a71916ee.jpg ] and [ http://www.gardenvisit.com/assets/madge/fountain_place_dallas/600x/fountain_place_dallas_600x.jpg ]

Dan Kiley is the star of modernist landscape architecture. Maybe not as creative as Burle Marx but, judging only from photographs, he achieved a higher quality in his work (both aesthetically and socially). I would not categorize either of their work as suprematist but Kiley was closer.

My reason for suggesting Kiley has suprematist influences was the close collaborative relationships he had with Bauhaus designers and the interest in revisiting structural and colour relationships as abstractions to break free from the constraints of traditional modes of thinking about the design of gardens, both in scale and function. The use of linear relationships, pure form (circles and squares)and repetition as spatial and aesthetic organising devices is particularly interesting.

From the AA files is the following statement:

“In the early 1940s, when the Bauhaus began to make a mark on American architecture, the free plan was reintroduced to the USA … This development is best illustrated by the influence of Mies van der Rohe on the practice of Dan Kiley.”

The landscape architect who, it seems to me, has been most influenced by Kasimir Malevich is Peter Walker, who describes this theme in his work as Minimalist. His best-known project will soon be Reflecting Absence – the National September 11 Memorial & Museum.

The work of Walker is very powerful and evokes strong emotions. The square fountains, movement of the water and context of a paved geometric yet irregular forest evoke a sense of strength, loss and resilience.

While the work of Suprematists is ‘modal’, the Neo-Minimalism of Walker reflects the trend towards the expression of raw emotion identifiable in the art of Mel Bochner.

[ http://www.brown.edu/Facilities/David_Winton_Bell_Gallery/bochner.html ]

When landscape architects look to fine art for inspiration they have a curious tendency to focus on the period from c1920-30. Thining about this in the 1970s, Jellicoe wrote that landscape architecture tend to ‘lag’ ’50 years behind the find arts’ but I think if writing today he would have to extend the period to ‘about 90 years’. Similarly, Tschumi and Hadid seem to have lost their hearts to the Russian Constructivists. The reasons could be political but I think it more likely that High Absract artists were concerned with principles in a way that is unusual in the fine arts.