- England

- Scotland

- France

- Holland

- Germany

- Italy

- Spain

- Portugal

- USA

- China

- Japan

- India

- Iran

- Advice

- Gardens

- England

- Scotland

- France

- Holland

- Germany

- Italy

- Spain

- Portugal

- USA

- China

- Japan

- India

- Iran

- Advice

- Garden Tours

Book: Landscape Planning and Environmental Impact Design: from EIA to EID

Chapter: Chapter 4 Public open space POS

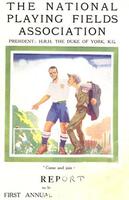

The park is dead. Long live the park.

In 'the city of dreadful night', circa 1850, acrid smoke belched from every rooftop and raw sewage flowed in narrow streets. Workers, with their wives and children, toiled from before dawn until after dusk. Zola describes such a life in Germinal (Zola 1885). On sunday, if the hapless workers had free time, most resorted to alcohol. It eased their pains, slaked their sorrows and helped them to dream of strikes and revolution. According to the cynical view of urban history, public gardens were provided by manipulative governments to control the rebellious tendencies of the working class. Ruskin described the public park in 1872 as a place where workers could be 'taken in squad' to be 'revived by science and art' (Robinson 1872). More charitably, public gardens were provided by public benefactors and enlightened city fathers who wished to improve the lot of the toiling masses. In either case, walls, fences and gates were essential, to discourage licentious behaviour and to make public gardens safe. In an earlier age, chains had been used to make library books safe against thieves. Imparked greenspace in urban areas became known as parks. Public baths and libraries were also provided. After six days of sordid toil, these facilities enabled workers to rest their limbs, cleanse their bodies and improve their minds. In parks, they could sit on a bench, look at the flowers, listen to brass bands and drive the moths from their Sunday clothes. In the early twentieth century, when machines took over the really heavy work, city managers espied a new role for parks: the promotion of physical fitness. During the First World War, soldiers proved to be less fit than their nineteenth century predecessors. After the war came economic depression and an outbreak of 'juvenile delinquency'. The governing authorities hoped that youthful energy could be diverted into organised sport [Fig 4.2]. Again, one can view their motives with cynicism or charity. Galen Cranz's enjoyable book on The politics of the park takes the cynical line and sees a progressive 'decline in the range of social functions performed by parks' and 'a practice of elites using parks deliberately as mechanisms for solving urban problems' (Cranz 1983: 225). 4.2 The governing authorities hoped that by filling parks with sportsfields they could diminish juvenile delinquency, as shown on the cover of the National Playing Fields Association's first annual report, for 1927. The NPAFs patrons were landed gentry and it looks as though one of them is befriending a 'working man'. Times have changed, somewhat. Library books are no longer chained to desks; houses have piped water and washing machines; private gardens are widespread. Industrial machinery does the physical work, leaving most people with sedentary jobs. For health and for leisure, sedentary workers require exercise, not rest. Organised sport shows no signs of diminishing "juvenile delinquency", though municipal authorities keep hoping against hope. Television has opened our eyes to all the different ways of enjoying outdoor life. Sitting in a municipal park, looking at the flowers and listening to the occasional brass band, does not feature prominently in surveys reviewing the popularity of leisure-time activities. Rather, people desire access to rich and varied landscapes with scope for many outdoor activities. Public authorities have redirected their efforts. Judging from the noticeboards displayed in public open spaces, they now aim to find out what activities people wish to persue - and then stop them from doing it.