- England

- Scotland

- France

- Holland

- Germany

- Italy

- Spain

- Portugal

- USA

- China

- Japan

- India

- Iran

- Advice

- Gardens

- England

- Scotland

- France

- Holland

- Germany

- Italy

- Spain

- Portugal

- USA

- China

- Japan

- India

- Iran

- Advice

- Garden Tours

Book: Landscape Planning and Environmental Impact Design: from EIA to EID

Chapter: Chapter 4 Public open space POS

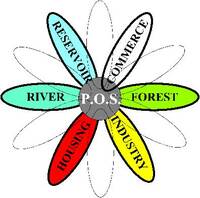

Park planners responded to the new age by tearing down park railings and planning webs of interconnected greenspace, originally known as park systems. The diagnosis was correct. The treatment was pathetically oversimplified. ' Parkland ', like most other types of land, should be planned for multiple objectives. New parks and new linkages should be created by planning recreational and conservation uses in conjunction with other land uses: urban reservoirs can make splendid waterparks; ornithological habitats and hides should be designed in conjunction with sewage farms; wildlife corridors should be planned beside roads, railways and streams; flood prevention works can yield canoe courses; public gardens can sit on top of office buildings; seclusion provides opportunities. 4.3 Public open space should be planned in conjunction with other land uses. The diagram shows six petals, representing land uses, interacting to produce a vibrant public open space (POS). New uses and new layers of interest should be brought into public open spaces [Fig 4.3]. This requires imaginative EID. Some open spaces could supply firewood and wild food (nuts, berries, herbs); others could infiltrate rainwater back into the ground, instead of allowing the water to accentuate flood peaks; sunday mark ets can fit well into parks. Every public open space can have a specialist use, in addition to its general functions: one could be a centre for kite flying [cross-ref to fig 4.4]; one for tennis; one for lovers of herbaceous plants; one for re-enacting military battles; one for every special recreational interest which has a magazine on your local newsstand. My local newsagent has special-interest magazines for golf, fishing, cycling, skiing, yachting, sail boards, fitness, martial arts, boxing, wrestling, horse-riding, climbing, trail walking, athletics, shooting, soccer, rugby, gardening, camping, model boats and model aircraft - but only six of these interests can be pursued in the 185 hectares of public open space near to where I live. In some respects, parks resemble churches. Both were built for idealistic reasons. Both are regarded as essential features of towns. Both can have attendance problems in the age of electronic communications. The world's great historic churches and parks are filled with visitors. But smaller local churches and parks need new roles. People dislike seeing churches turned into shops, or public parks into markets, but a greater range of uses is necessary. The time has come to re-invent and re-engineer the public park. Many of the ancient public open space archetypes continue to have value. But they must be adapted to the conditions of today. Too many planning maps indicate 'public open space' with green ink, as though it were all the same, suitable for management in one way by one organisation. On a proper open space map, that vapid green ink should be replaced by a harlequin mosaic of disparate hues and shades, reflecting the kaleidoscopic variations of spatial use, management and ownership. To produce such a map, it is necessary to carry out surveys, of ownership, use, values and methods of maintenance. Towns need a great diversity of public open space types. In addition to the emerald green of public parks, they need spaces which are diamonds, rubies, pearls, ambers, ceramics, lucky charms, holograms and electronic marvels too. The list of open spaces which will be discussed in subsequent sections of this chapter includes: commons, municipal parks, sports parks, squares, plazas, public gardens, village greens, national parks, private pleasure grounds and festival parks.