- England

- Scotland

- France

- Holland

- Germany

- Italy

- Spain

- Portugal

- USA

- China

- Japan

- India

- Iran

- Advice

- Gardens

- England

- Scotland

- France

- Holland

- Germany

- Italy

- Spain

- Portugal

- USA

- China

- Japan

- India

- Iran

- Advice

- Garden Tours

Book: Landscape Planning and Environmental Impact Design: from EIA to EID

Chapter: Chapter 11 Urbanisation and growth management

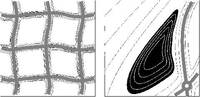

The construction of a new town is bound to necessitate the excavation and deposition of very large quantities of earth. Since landform is one of the main aspects of landscape design it is surprising that the subject has not received more attention in master plans. Milton Keynes has been criticised for its spoil disposal policy but the 1970 Master Plan for the town is exceptional in having a section on earthmoving, written by Youngman: Much may be disposable locally, within the range of scrapers and graders, for specific uses or for scenic purposes in reï¾shaping the existing topography. Provided designs are ready at the time the soil is to be shifted, this would be the most economical way of disposing of it. But in some areas (factory sites and the city centre for example) this will not be so easy; and there will be considerable quantities of soil to be carted from development sites. Ideally this should be put to positive use... here is a landscape material as useful as vegetation and it should not be squandered. A long term programme of organised tipping is needed (Milton Keynes Development Corporation 1970: 326). When Walter Bor came to reappraise the master plan for Milton Keynes in 1979, he criticised the 'wellï¾intentioned but mistaken landscape policy [of] making more generous road reservations than envisaged in the original plan' which tend to 'accentuate the fragmented overall appearance of Milton Keynes' (Bor 1979: 243). In a similar vein, Reyner Banham wrote that 'substantial earth banks, put there with the laudable intention of containing traffic noise' have turned the roads into 'a private landscape world, without contact with the real landscape beyond the banks' (Banham 1979: 359). The problem arose because the Development Corporation did not prepare a 'long term programme of organised tipping'. Large quantities of surplus material were simply tipped beside the grid roads and transformed too many of them into what appear as deep cuttings. They may be splendid when the trees reach maturity, but their character will be rural, not urban (Bor 1979: 243). There are so few views of the town that the roads have had to be numbered and prefixed with the letters 'H' or 'V' so that visitors know whether they are traversing the grid horizontally or vertically. Only long-term residents become familiar with the road system. The supply of construction materials is another aspect of earthmoving. It includes crushed rock for roadstone, sand and gravel for concrete, structural fill for foundations, and nonï¾structural fill for other types of embankment. If these materials can be quarried from the new town site there will be significant savings in transport costs. Careful site selection for quarries will also enable the land to be shaped for a particular afterï¾use. At Redditch, the road engineers planned to destroy three attractive hills to build an embankment. This policy was opposed on landscape grounds and a study of the drift geology revealed that an alternative supply could be obtained by excavating what is now the Arrow Lake, a considerable amenity for the town [Fig 11.14]. It was obtained 'free', as a sideï¾effect of the road construction programme (Turner 1974). Advance planning of earthmoving operations saves money. There is a great risk of doubleï¾handling if the excavation components of different building contracts are not considered at the outset. It is only too easy for contractors to make arrangements so that the same item of work is paid for in one contract as 'removal of excavated material from site' and then paid for in another contract as 'supply of approved filling material'. If 25 million cubic meters of earth are being moved at a cost of ,5/m3 it is evident that inadequate landscape planning can lead to waste on a large scale. Earthmoving plans must be produced in advance of urbanisation [Fig 11.15]. They have enormous creative potential. 11.15 The earthmoving policy for Milton Keynes New Town (left) resulted in a fragmented landscape. The earthmoving policy for Redditch New Town (right) saved a hill and created a lake.