Hence it is commonly observed by those who have seen both St. Peter's, at Rome, and St. Paul's, at London, that the latter appeared the largest at the first glance, till they became aware of the relative proportion of the surrounding space; and I doubt whether the dignity of St. Paul's would not suffer if the area round the building were increased, since the great west portico is in exact proportion to the distance from whence it can now be viewed, according to the preceding table of heights and distances: but if the whole church could be viewed at once, like St. Peter's, the dome would overpower the portico, as it does in a geometrical view of the west front*.

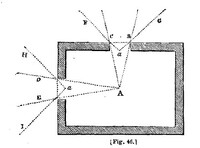

It is evident, that a spectator at A can only see, through an aperture of four feet, those objects which fall within the opening B c, in one direction, and D E in the other, neither comprehending more than twenty or thirty degrees. But if he removes to a, near the windows, he will then see all the objects, within the angle F G, in one direction, or H I in the other; yet it is obvious, that, even from these spots, that part of the landscape which lies betwixt the extreme lines of vision F and H, will be invisible, or at least seen with difficulty, by placing the eye much nearer to the window than is always convenient.

From hence it follows, that to obtain so much of a view as may be expected,* it is not sufficient to have a cross light, or windows, in two sides of the room, at right angles with each other; but there must be one in an oblique direction, which can only be obtained by a bow window: and although there may be some advantage in making the different views from a house distinct landscapes, yet as the villa requires a more extensive prospect than a constant residence, so the bow window is peculiarly applicable to the villa. I must acknowledge that its external appearance is not always ornamental, especially as it is often forced upon obscure buildings, where no view is presented near great towns, and oftener is placed like an uncouth excrescence upon the bleak and exposed lodging houses at a watering place; but in the large projecting windows of old Gothic mansions, beauty and grandeur may be united to utility. *[Of this I observed a curious instance at HOOTON HOUSE, from whence a distant view of Liverpool, and its busy scenery of shipping, is not easily seen without opening the windows, while the difference of a few yards, in the original position of the house, would have obviated the defect, while it improved its general situation.]

*[I have sometimes thought that this same rule of optics may account for the pleasure felt at first entering a room of just proportions, such as twenty by thirty, and fifteen feet high; or, twenty-four by thirty-six, and eighteen feet high; or, the double cube, when it exceeds twenty-four feet.] The field of vision, or the portion of landscape which the eye will comprehend, is a circumstance frequently mistaken in fixing the situation for a house; since a view seen from the windows of an apartment will materially differ from the same view seen in the open air. In one case, without moving the head, we see from sixty to ninety degrees; or, by a single motion of the head, without moving the body, we may see every object within one hundred and eighty degrees of vision. In the other case the portion of landscape will be much less, and must depend on the size of the window, the thickness of the walls, and the distance of the spectator from the aperture. Hence it arises, that persons are frequently disappointed, after building a house, to find that those objects which they expected would form the leading features of their landscape are scarcely seen, except from such a situation in the room as may be inconvenient to the spectator; or, otherwise, the object is shewn in an oblique and unfavourable point of view. This will be more clearly explained by the following diagram [fig. 46].