- England

- Scotland

- France

- Holland

- Germany

- Italy

- Spain

- Portugal

- USA

- China

- Japan

- India

- Iran

- Advice

- Gardens

- England

- Scotland

- France

- Holland

- Germany

- Italy

- Spain

- Portugal

- USA

- China

- Japan

- India

- Iran

- Advice

- Garden Tours

Book: Landscape Planning and Environmental Impact Design: from EIA to EID

Chapter: Chapter 3 Context sensitive design theory

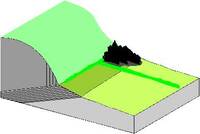

Design control works best with the aid of forward-looking plans. Britain 's Town and Country Planning system, as enacted in 1947, contained a novel approach to the control of development. It rested on a marriage of flexible zoning with EA-type development control. Zoning took the form of statutory development plans, which each planning authority was required to prepare. The EA-type controls took the form of a requirement that each land owner must obtain 'planning permission' before undertaking a development project. Each project is considered by planning officials and by elected members representing the local community. They have wide discretion. John Punter carried out a detailed study of how the system has functioned in one English city. Bristol was a great seaport. From an estuary in the west of England , the city's merchant adventurers sallied forth, prospered with the 'empire of the seas', and declined when that empire declined. Severe bombing during the Second World War left great scope for re-development and environmental improvement. The 1947 Town and Country Planning Act gave city authorities very considerable powers to regulate this development. The final section of Punter's book contains a drawing [Fig 3.9] and a photographic inventory of the 250 major office building projects from 1940 to 1990. It is deeply depressing. Each of the 250 buildings was subject to full design control. Yet most of the buildings stand out from the city like stained teeth in the gaping mouth of a poor old tired horse. Their relationship to each other and to their context lacks beauty and harmony. The drawing is a fearful indictment of the development control system. There is but one happy moment in Punter's tale: the 1977 Townscape and Environment Topic Study. Punter writes that: This extraordinary document must be one of the most comprehensive and intelligible townscape studies ever undertaken in British planning. (Punter, 1990) The objective of the study was 'to revitalise the obsolete urban structure by the injection of new functions and activities and the forging of new linkages between the City and the Floating Harbour ' (City of Bristol, 1977). It operated in conjunction with the City's conservation policy. By defining the character of the old town centre and the historic docks, it enabled their character to be protected and enhanced. In effect, this provided: - a pedestrian plan, for a riverside walk - a spatial plan, for the dock basins to have a coherent building frontage - an architectural plan, for new buildings to have a 'dockside character' - a colour plan, for dockside buildings to be faced in traditional red brick - a vegetation plan, to encourage more planting in waterside areas Yet the Townscape and Environment study is surprisingly thin on positive urban design advice. It relies on a detailed appreciation of the historic environment, and a set of diagrams [Fig 3.10], to set forth the above principles. Compliance with some other principles would also have been desirable: - a surface water plan, for the detention and infiltration of rainwater - a habitat plan, for creating new habitats for plants and animals - a bicycling plan, for creating paths and parking facilities throughout the city - a seating plan, for creating a network of sitting places which satisfy the criteria for good seating From an EA point of view, the key feature of the above project modifications is that they relate as much to desirable future states of affairs as to the existing environment: they are not mere 'mitigation'. The impact of the project on the re-establishment of a dockland character was just as important as the impact on the existing environment. As Punter comments, design control at its best is 'an exercise in applied urban design'. Environmental assessors must consider the impact of a project both on what does exist and on what could exist. The Bristol Townscape and Environment study served as what was called a 'lighthouse plan' in the previous chapter. It enabled the planners and the planned to chart a course through choppy waters, though sometimes they hit the rocks. At Portwall House 'negotiations continued over the colour of the mortar to be used with the City preferring black but the architects preferring brown or purple' (Punter 1990: 178). One imagines a drab municipal office with tireless bureaucrats confronting devitalised architects, day after day, week after week, month after month. Since black mortar, in my opinion, looks vile with red brick, I find it impossible to see its use as matter of public policy. The Portwall House negotiations read like a scandalous waste of professional time and public money. They help to explain why architects detest the idea of design control. Moro summarised the case against aesthetic control in 1958 (Moro, 1958): 1. It stifles architectural expression. 2. It encourages uniformity and discourages contrast. 3. It causes hardship to those affected: client and architect. 4. it usually discriminates against those who are exercising their traditional right of wanting to live in a house of their time. 5. It gives undue power of judgement to officials without aesthetic training. 6. it smacks of Totalitarianism and is, in fact, a characteristic adjunct of such a form of government. 7. It is humiliating to the architect and makes nonsense of his professional status. 8. It puts those architects into an invidious position who lend themselves to the distasteful task of sitting in judgement over their colleagues. 9. It rarely stops bad conventional building. 10. It often stops good unconventional building. With regard to Moro's fifth point it should be said that the influence of the elected chairman of the planning and development control committee can be more powerful than that of officials. Indeed, our Australian would have a very good chance of obtaining permission if he owned the golf club at which the chairman played. John Punter, a planner, responded to Moro's list by giving the case for design control 'in equally abbreviated and dogmatic form' (Punter, 1990): 1. It prevents 'outrages' and stops much bad building. 2. It raises the standard of much development by ensuring more thought goes into its design. 3. It encourages the architect to stand up to his client who may often want only the cheapest building to sell on to another user/owner. 4. It is a democratic process (of sorts) because it incorporates the views of the public. 5. It is accountable because decisions are made by elected representatives. 6. It provides a necessary bridge between lay and professional tastes. 7. Architecture is the most public of arts, and it is not merely the client who is forced to look at a building for many generations. An impassioned debate along these lines has raged between Britain 's architecture and planning professions for half a century. Both sides had good points. If design control leads to coherent cities with riverside walks, please can we have more of it. But if design control leads to wasteful bickering and bureaucratic interference with good architecture, let's be rid of it. In Bristol , design control succeeded in the context of an urban design strategy for the future character of the docks. So let's have more urban design strategies. A significant aspect of the Bristol situation is that the urban strategy was historicist. It sought to re-create the spatial and architectural forms of a once-great seaport. In many places, like Bristol , this is an excellent policy. Elsewhere, it is right to encourage new spatial structures and new architectural styles. Progress would be impossible if this were not the case. The Sydney Opera House and the Louvre Pyramid were great innovations, once doubted and now loved. On different occasions, as will be discussed in Part 2 of this book, a powerful case can be made for developments which are 'Similar to', 'Identical with', or 'Different from' their surroundings [Fig 3.11]. Policy decisions need to be made within a policy framework. Principles are required. Fig 3.11 L�vi Strauss used a geological analogy to explain the relationship between surface structure and deep structure. The Bristol study indicates that design controls, and 'mitigation' under environemntal assessment procedures, can be effective only when they operate within a framework of existing-site information and forward-looking 'lighthouse plans'. Favourable impacts need to be designed. Environmental assessment should operate in tandem with land use planning. Without a policy framework, EA over-emphasises the status quo. Some projects may be stopped and some harmful side effects may be mitigated, but the many ways in which the environment can be improved are not sufficiently taken into account. If we accept that governments have a right to intervene in land use decisions, we must have theories of context to establish criteria for individual cases. Without contextual policies, our Australian will never get a fair deal. Part 3 What to achieve by intervention