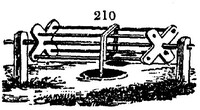

742. Persian gardening, as an art of culture, is not understood to be far advanced, notwithstanding the excellence of its native productions. Nature, as Sir William Temple observes, has done too much, for art to have an adequate stimulus for exertion. Till our intercourse with North America and China, not only the finest fruits, but the most fragrant and showy flowers, were obtained from Persia. The aboriginal horticulture of these countries consists chiefly in the culture of the native fruits, the variety of which is greater than that indigenous to any other country. The peach, the palm tribe, and, in short, every fruit tree cultivated in Persia by the natives, are raised from seed, the art of grafting or laying being unknown. Water is the grand desideratum of every description of culture in this country. Without it nothing can be done, either in agriculture or gardening. It is brought from immense distances, at great expense, and by very curious contrivances. One mode practised in Persia consists in forming subterraneous channels at a considerable depth from the surface, by means of circular openings at certain distances, through which the excavated material is drawn up (fig. 210.); and the channels so formed are known only to those who are acquainted with the country. These conduits are described by Polybius, a Greek author, who wrote in the second century before Christ; and Morier (Journey to Persia) found the description perfectly applicable in 1814. Doves' dung, the same author observes, is in great request in Persia and Syria, for the culture of melons. Large pigeon-houses (fig. 211.) are built in many places, expressly to collect it. The melon is now, as it was 2500 years ago, one of the necessaries of life, and it has been supposed that, when the prophet Isaiah, meaning to convey an idea of the miseries of a famine, foretold that a cab of doves' dung would be sold for a shekel of silver, he referred to the pigeons' dung required for the cultivation of the melon. We have elsewhere shown (ᄎ 40.) that this appears to be a mistake. Sir John Malcolm says, that, when he was in Persia (A. D. 1800), grapes were sold at less than a halfpenny a pound; while, in some provinces, fruit had scarcely a nominal value. (Bucke's Beauties, &c. of Nature.)