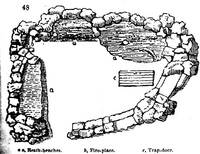

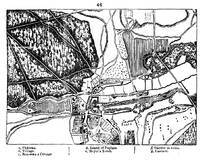

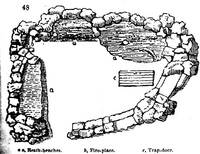

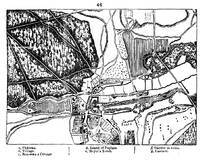

217.The English style of gardening began to pass into France after the peace of 1762, and was soon afterwards pursued with the utmost enthusiasm. Hirschfeld affirms that they set about destroying the ancient gardens, and replanting them in the English manner, with a warmth more common to the mania of imitation than the genius of invention. Even a part of the gardens of Versailles was removed, as Delille laments (Les Jardins, 4th edit., p. 40.), to make way for a young plantation a l'Anglaise. Laugier is the first French author who espoused the English style of gardening, in his Essai sur l'Architecture, published in 1753; and next in order Prevot, in his Homme du Gout, published in 1770. About the same time, the first notable example was preparing at Ermenonville, the seat of Vicomte Girardin, about ten leagues from Paris. An account of this place was written by Girardin himself, in 1775, and published in 1777. It was soon after translated into English, and is well known for its eloquent descriptions of romantic and picturesque scenes. Morel observes, in his Theorie des Jardins, published in 1766, that very little had been done previously to 1766: he mentions that he had been consulted as to Ermenonville, and states that the Duc d'Aumont's park at Guiscard, and a seat near Chateau Thiery, were chiefly laid out by him. Soon after Morel's work, Delille's celebrated poem (Les Jardins) made its appearance, and is perhaps a more unexceptionable performance than The English Garden of Mason. The French, indeed, have written much better on gardening and agriculture than they have practised; a circumstance which may be accounted for from the general concentration of wealth and talent in the capital, where books are more frequent than examples; and of professional reputation in that country depending more on what a man has written than on what he has done. It does not appear that English gardening was ever at all noticed by the court of France. Ermenonville (fig. 46.) appears to have been laid out in a chaste and picturesque style, and in this respect to have been somewhat different and superior to contemporary English places. The chateau was placed on an island in the lake, near the village. Among other objects in the grounds were Rousseau's cottage (figs. 47, 48.); his tomb in the Island of Poplars; that of the landscape-painter G. F. Meyer, who had assisted Girardin in designing the improvements, in an adjoining island; a garden in ruins, and the grand cascade. Useless buildings were in a great degree avoided, and the picturesque effect of every object carefully considered, not in exclusion of, but in connection with, their utility. There is hardly an exceptionable principle, or even direction, referring to landscape-gardening laid down in the course of Girardin's Essay; and in all that relates to the picturesque, it is remarkable how exactly it corresponds with the ideas of Price. Girardin, high in military rank, had previously visited every part of Europe, and paid particular attention to England; and before publishing his work he had the advantage of consulting those of Whately, Shenstone, G. Mason, and Chambers, from the first of which he has occasionally borrowed. He professes, however, that his object is neither to create English gardens nor Chinese gardens, and less to divide his grounds into pleasure-grounds, parks, or ridings, than to produce interesting landscapes, �paysages interessans,� &c. He received the professional aid of J.M. Morel, who afterwards published Theorie des Jardins, and probably that of his guest Rousseau, who seems to have composed the preface to his book. Magellan, in the Gazette Litteraire de l'Europe for 1778, in giving some account of the last days of Rousseau, who died at Ermenonville, and was buried in the Island of Poplars there, informs us, that Girardin kept a band of musicians, who constantly perambulated the grounds, making concerts sometimes in the woods, and at other times on the waters, and in scenes calculated for particular seasons, so as to draw the attention of visitors to them at the proper time. At night they returned to the house, and performed in a room adjoining the hall of company. Madame Girardin and her daughters were clothed in common brown stuff, en amazones, with black hats, while the young men wore �habillemens le plus simples et le plus propres a les faire confondre avec les enfans des campagnards,� &c. Ermenonville in October, 1828. The property was then to be sold, and was let in the mean time to the Prince de Conde, who made no other use of it than as a preserve for game. The tower of the fair Gabrielle was roofless, and going fast to decay; some of the other garden structures were wanting; all were more or less dilapidated, with the exception of Rousseau's tomb in the Island of Poplars, and what is called �La maison du Philosophe� (figs. 47. and 48.), which is still pointed out to strangers as a place where Rousseau used to spend whole days, reposing on its heath benches (fig. 48.), having a fire of logs in the rude fire-place, and supplying himself with water from an adjoining spring. Bread and wine, we were told, the benevolent proprietor placed every morning in the cellar below, which Rousseau entered by a trap-door in the floor. The house in the village in which Rousseau lived, and the room in which he died, used to be shown to strangers: the room we were told (in 1828), was become the sleeping room of one of the Prince de Conde's gamekeepers. Ermenonville having little or no natural beauty, and being now neglected by art, has ceased to be interesting otherwise than by historical associations. (See Trois Jours en Voyage a Chantilly, Mortefontaine, et Ermenonville, &c., 1828.) Ermenonville in 1848. This garden is now so much neglected as scarcely to retain any traces of its former beauty.