- England

- Scotland

- France

- Holland

- Germany

- Italy

- Spain

- Portugal

- USA

- China

- Japan

- India

- Iran

- Advice

- Gardens

- England

- Scotland

- France

- Holland

- Germany

- Italy

- Spain

- Portugal

- USA

- China

- Japan

- India

- Iran

- Advice

- Garden Tours

Book: Landscape Planning and Environmental Impact Design: from EIA to EID

Chapter: Chapter 7 Agriculture, farming and countryside policy

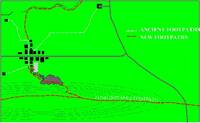

There is a great demand for rural recreation, for which the public is willing to pay. Western civilisation has lived with the dream of rural happiness since ancient times [Cross ref to illustration of Jacob & Laban]. Perhaps it is rooted in memories of a time when man lived closer to nature. Horace and Virgil took the idea of 'rural retirement' from the Greek poets and passed it to renaissance poets and to ourselves. Philosophers, artists, politicians, soldiers, captains of industry, all dream of rural peace and tranquillity. Middle and upper-income people with the means to pay for it, seek to spend their weekends, vacations and retirement years in the countryside. As societies becomes richer and transport becomes relatively cheaper, the demand for rural recreation has grown and will grow. People want beautiful scenery, as discussed above, but they also want physical access to the countryside. Access is a public good. Its supply can be diminished or increased. Historically, it has diminished. Under the feudal system, land belonged to kings or lords but individuals had rights of access, grazing, food and fuel gathering over large tracts. These rights were progressively eroded during the agricultural revolution. Common lands were enclosed and 'democratic' parliaments, in which only landowners were represented, voted to increase landowners rights and decrease other common rights. There is every reason for the more democratic parliaments of modern times to reverse the process. In Britain, this has been happening since the 1947 National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act. The process has been slow, because it is seen as a recreational policy, instead of as a policy of diversifying the output from farms to embrace agricultural and non-agricultural goods. It used to be assumed that people visited public parks for either 'formal' or 'informal' recreation. The former meant organised games. The latter meant walking and sitting. Comparable over-simplifications were applied to countryside recreation. It is assumed that people either wish to walk or to visit attractors, such as museums, castles, picnic sites and golf clubs. In fact, most things can take place in the countryside: sleeping, running, food gathering, courting, digging, planting, car washing, painting, watching wild life and catching butterflies. Some of them require plans. Walking is a good example of an activity which needs to be planned. Britain is fortunate to have a network of public footpaths but unfortunate that the network came into existence for a society which is wholly unlike our own [Fig 7.12]. The footpath routes led from farmsteads to hamlets which have gone out of existence, to churches which are no longer used, to markets which no longer take place. There is no need for the historic rights of way to be extinguished. But there is a great need to plan new routes to serve the needs of our own time [Fig 7.13]. The new network, of countryways, should run from origins to destinations along lines of opportunity. Routes along hilltops and valleys are very suitable. Links between roads and beaches are very important. The provision of a walkway network, as a public good, need have little effect on the production of private goods from what would remain privately owned land. But rights of access may need to be purchased and farmers should be rewarded for any work they do to maintain footpaths, gates and stiles. 7.13 New footpaths should be planned, to serve the needs or our own time.