I came across this attractive photo and wise caption on Flickr. The Archaeological Survey of India (AIS) was set up by the British in 1871 and it looks as though their gardening staff still do apprenticeships in Britain’s parks departments. Great Indian works of art are treated with lawns, rose beds (Hybrid Teas preferred) and Bougainvillea – a native of South America. One could argue that Sanchi, as the best-oldest Buddhist site has had a massive influence on garden design, and therefore deserves this treatment. But I would rather use the photo to argue that there is an enormous need for garden designers and landscape architects to become involved with appropriate design for archaeological sites. It is far too serious a matter to be left to the whims of archaeologists, garden managers or tourism ‘experts’.

Branding the landscape

my first post for gardenvisit, so i thought i’d pose a question thats been on my mind for a while. also it ties in neatly with Toms post below.

Is there too much public art in the landscape? reports say that there has been a massive boom in public art commisions in the UK over recent years, and I’ve applied for a few of them myself! so I’m playing devils advocate here, or being a hypocrite, whatever way you want to look at it.

all the same, it seems you can’t go anywhere now without there being some sanctioned artwork there to explain the place to you – telling you what you should be thinking and explaining how you should be feeling. isnt there room any more for ambiguity, or an individual respone. can’t a place just be a place?

the adlesburgh scallop (pictured) makes a good case study. a source of recent controversy, its detractors say there is nothing wrong with the artwork itself, but its location was beautiful..more beautiful without it. it is an unnecessary detraction.

the artist says that they dont understand the work – that it was created especially for that location. the insinuation is that as an artist, her response is more valid than everyone elses. more valid than the place itself which should serve as a setting for her work.

the council say it works because it has attracted more visitors to the site. nature on its own is boring, and hard to sell. who wants to be left with only their surroundings and their own thoughts? best to give them the ‘proper interpretation’ so they can get their thoughts in order. and this i think now is the real role of public art – an exercise in branding and marketing, a logo for the landscape

Henry Moore's sculpture in landscape and garden.

Henry Moore said that “I would rather have a piece of sculpture put in a landscape, almost any landscape, than in or on the most beautiful building I know.” He made a good point and when traveling by train I often think of his remark that one should not waste one’s time reading – because it is such a wonderful opportunity to look out of the window and think and think. Railway lines make a cleaner cut than roads, producing a cross-section through the land.

Henry Moore said that “I would rather have a piece of sculpture put in a landscape, almost any landscape, than in or on the most beautiful building I know.” He made a good point and when traveling by train I often think of his remark that one should not waste one’s time reading – because it is such a wonderful opportunity to look out of the window and think and think. Railway lines make a cleaner cut than roads, producing a cross-section through the land.

I very much like Moore’s sculpture in the landscape but I’m not so sure about putting it in gardens – they are are too close to ‘the most beautiful building I know’. The sculpture in Kew Gardens is a case in point. It looks right because it has a ‘landscape setting’

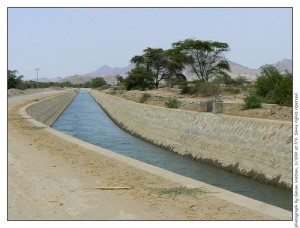

Multi-objective water conservation in India

Multi-objective design being more characteristic of traditional societies than modern ‘scientific’ societies, India has the best record in the design of structures related to water conservation. This step well, in Abhaneri, is a temple and a place of resort in hot weather – as well as a water tank and a place to wash. Such structures are found throughout the Indian subcontinent, though many were put out of use by British engineers who saw them as breeding grounds for the malarial mosquito. They are known as baolis or hauz, and many other names, in India and are often called stepwells in English because of the steps which give access to the water at whatever level. The design of step wells and ghats (steps to water) was fully integrated with other aspects of town design. Today, most of them are neglected and rubbish-filled. It is a pity – and too late to blame the imperialists.

I have been reading Amita Sinha’s book on Landscapes in India: forms and meanings (2006). An associate professor of landscape architecture at the University of Illinois, Urbana Champaign, she writes that ‘Rivers, mountains, seashores, and forest groves nurture the rich mythology of gods and goddesses. The association of pilgrimage centers with water can be clearly seen in the number of sacred spots that lie on riverbanks, at concluences, or on the coast. The devotees bathing in rivers on particularly auspicious days gather spiritual merit (punya) and are absolved of their sins. Along with mountains, water is one of the most important natural elements in Hindu mythology, and most sacres sites contain one or both of these elements. Many temples are along riverbanks; others have water in the form of lakes, ponds, or built tanks. Tanks are essential at any worship complex’. London has many, welcome, migrants from the Indian subcontinent and I wish their traditions were employed in the planning and design of the River Thames landscape. See review of London’s riverside landscape and riverside walks.

Anti-architecture and anti-landscape architecture

Christine wonders if I am anti-architect and I thought, after a little introspection, that a public reply would be worthwhile. I would like this blog to be an interface between architecture, landscape architecture, garden design and planning – and regret it if I come over as more anti-architect than anti- the other environmental professions. I have worked with architects all my professional life, though more as a teacher than a designer, and have often found them to be more creative and more technical than many other built environment professionals. But I regard the twentieth century as a bad period in the history of urban and landscape planning – and part of the blame lies at the feet of the professions. Another, larger, part is an unwanted consequence of professional specialization. But perhaps the largest part is the fragmentary arrangements for commissioning work. River control structures, for example, are commissioned by specialized river authorities with no mandade to spend money on anything except riverworks. They might even be called up before the auditors if they ‘wasted’ money on architectural or landscape objectives. But when an abomination has been created, it is simplest and blame the designers and they do not lack culpability.