Landscape architecture: an apocalyptic manifesto, was the title of a landscape architecture manifesto published in 2004 by Heidi Hohmann and Joern Langhorst (and republished as ‘Landscape Architecture: A Terminal Case?’ in Landscape Architecture Magazine 95, no. 4 (April 2005): 26-45.). The original manifesto is still available as a pdf document. The Hohmann-Langhorst diagnosis was as excellent. Their prognosis was pessimistic and melancholic.

Having a nostalgic affection for manifestos, I responded with my own manifesto – and plan to mark its 10th anniversary with a revised version.

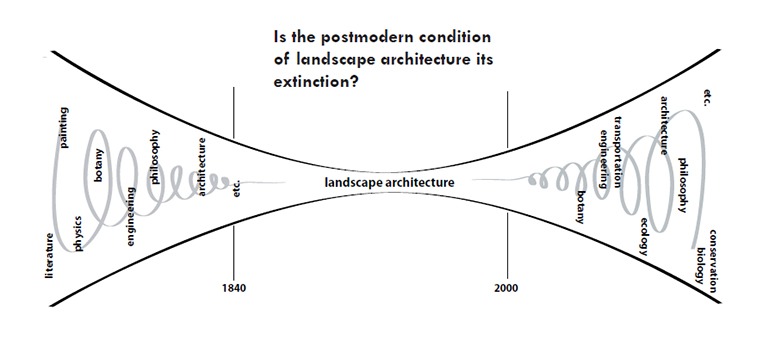

The above diagram, from the Hohmann-Langhorst article, shows the disciplines from which landscape architecture emerged and the disciplines into which they expected it to dissolve. Worldwide, this has definitely not been landscape architecture’s fate in the last decade. It has had a great many successes without, in my view, coming near to realising its full potential.

There is a great contrast between the two countries (Britain and America) which gave birth to landscape architecture as an organized profession. Landscape architecture is flourishing in the US and stagnant in the UK. It could be that the Hohmann-Langhorst article stimulated the US profession to examine its navel and engage in renewal and re-generation. In part, the regeneration has come from the body of theory known as Landscape Urbanism. Proponents have had many competition successes and advocates of New Urbanism feel themselves under threat. Andres Duany and Emily Talen have responded with a book on Landscape Urbanism and Its Discontents: Dissimulating the Sustainable City. The blurb to their book (which I have not yet read) states that ‘While there is significant overlap between Landscape Urbanism and the New Urbanism, the former has assumed prominence amongst most critical theorists, whereas the latter’s proponents are more practically oriented.’ This is despite the fact that Landscape Urbanists have done a poor job of explaining themselves. They should be grateful to Ian Thompson for his account of its Ten Tenets – and I hope his clarity will stimulate the much-needed revival of English landscape architecture. It is of interest that one of the landscape architects with the clearest vision of where the profession should be heading was born in the UK and works in the US – see this interview, in which Time Magazine describes James Corner as an Urban Dreamscaper.

Category Archives: Urban Design

Happy New Year 2014 – and may it be free of GREENWASH

The Oxford English Dictionary offers this useful definition of greenwash (n)

The Oxford English Dictionary offers this useful definition of greenwash (n)

Pronunciation: Brit. /ˈɡriːnwɒʃ/ , U.S. /ˈɡrinˌwɔʃ/ , /ˈɡrinˌwɑʃ/

Etymology: < green adj. + wash n., after whitewash n.

Misleading publicity or propaganda disseminated by an organization, etc., so as to present an environmentally responsible public image; a public image of environmental responsibility promulgated by or for an organization, etc., regarded as being unfounded or intentionally misleading.

1987 D. Bellamy in Sanity Sept. 28/1 They create a lot of environmental ‘greenwash’, and thank god for it, because they create some very good nature reserves. But they’re also commissioning uneconomic nuclear power stations.

1989 Observer 5 Mar. 14/2 Six Ministers launched ‘Environment in Trust’, a clutch of pastel-shaded leaflets putting a greenwash over the Government’s environmental record.

1993 New Scientist 10 Apr. 22/2 While they can be useful, these sorts of standards are sometimes used quite cynically—as corporate greenwash.

2003 Managem. Today Jan. 45/2 Companies only report what they want to report, and it’s mostly greenwash and PR.

London's proposed new Garden Bridge

Let us join the chorus of support for London’s Garden Bridge. The government and the Greater London Authority have promised to pay half the cost – so finding the rest should be a formality. The idea was conceived by the star actress Joanna Lumley in 1998 (she is also a patron of the Druk White Lotus School). But her idea slept for 14 years, until TfL asked for ideas about new ways of crossing the Thames. Thomas Heatherwick, working with Arup (coincidentally the architects for the Druk School), published the above design last summer – and half the funding was promised this month. The Garden Bridge will be 367 metres long and 30 metres wide at its widest point. It will connect a point near Temple station to a point near Gabriel’s Wharf on the South Bank Centre.

As an idea, it is wonderfully superior to Hungerford Bridge and, of course, to the London Eye. But what all three projects teach us is THE DESIGN PROFESSIONS SHOULD NOT WAIT TO BE ASKED. If designers, especially landscape architects (because of their concern with the public realm), have a good idea then they should draw it and publish it.

Useful links re the Garden Bridge:

TfL consultation on the Garden Bridge

Garden Bridge Trust website (with video)

Hermitage Wharf, Joseph Conrad, Norman Foster and the River Thames Landscape

The above photograph from Tower Bridge was taken yesterday on my way to the cycle petition hand-in. It struck me as a real Joseph Conrad view of the river and Andrew Cowan Architects design for Hermitage Wharf looks much better than Foster’s design for Albion Riverside. Then I remembered having written a critical comment on Hermitage Wharf a few years ago. Checking it, I was pleased to find that I had praised the architecture and that it was the wretchedly dull riverside space I had criticised. Maybe Tower Hamlets’ planners mandated a bad landscape design because of the South Bank type crowds they were anticipating?

Lord Norman Foster's Thames-side Boom Boxes

We are pleased to publish the hitherto-unseen concept which so evidently inspired Lord Norman Foster’s pair of Thames Boomboxes. As previously agreed, Lord Norman does ‘an awfully good box‘. His heart is in the right place: he speaks with enthusiasm about urban design and works with good landscape architects. The problem, I fear, is that his head is in the wrong place. He sees buildings as objects, not as the creators of space. His own office (the left-hand building, above) is a fine box. But, like a hifi box or another consumer product, it could fit equally well in any context. There is nothing-London and nothing-Thames about it or the curvy adjoining residential boombox – except of course for its wannabe name: The Albion. The above photograph was taken on a warm day in late summer. Re-visited last week a howling gale was being funneled through the arch under the Albion. The ambient temperature was 11C and, with wind-chill, felt like -1C. So, while perfectly able to admire Foster and Partners architecture, I condemn this example of the firm’s the landscape architecture and urban design. The half-doughnut building faces due north, so that its wings keep out all sunlight except for mid-day in mid-summer. This is not my idea of good conditions for enjoying a good outdoor life beside a great river.

The skyline, architecture and landscape of the River Thames in Central London

I see the Banks of the Thames as a place where, during the twentieth century, unimaginative planning and selfishly mediocre architecture often conspired to produce designs better suited to a rundown provincial town than to the heart of a great city. Skylines, landscape and architecture should be considered together, looking to the past and looking to the future. ‘Protecting’ views is important but insufficient. Proposals for ‘high buildings’ ‘tall buildings’ and ‘towers’ should be viewed in context, never in isolation. Studies of their visual and environmental impact require scenic quality assessments, a policy context and full testing on a digital model of the city. As the below quotations reveal, London’s river is both a Place of Darkness and a Place of Light.

William Blake, in 1794, found ‘in every face I meet / Marks of weakness, marks of woe’ where ‘the Thames does flow’.

William Wordsworth, 8 years later found the Thames a river of beauty and romance. He declared that ‘Earth has not anything to show more fair’ (1802).

Joseph Conrad, in 1899, knew the Thames as a place of history, romance, toil, darkness and light. He saw London as ‘the biggest, and the greatest, town on earth’, a place which had known ‘the dreams of men, the seed of commonwealths, the germs of empires’ and was yet ‘one of the dark places of the earth.’

Since 1945 property developers have seen the Thames as a place to make a quick buck

Since 2000, some wealthy immigrants have viewed riverside apartments as great places to launder the ill-gotten gains of financial scams and miscellaneous corruption.

Recent blog posts about London’s River Thames skyline landscape

- The 122 Leadenhall Cheesegrater and protecting London’s skyline landscape view of St Paul’s Cathedral from Fleet Street

- The Shard architecture and skyline landscape symbolic reviews

- Sunlight, tall buildings and the City of London’s new urban landscape architecture

- The visual impact of Renzo Piano’s Shard on the landscape and skyline of the River Thames

- London’s skyline: landscape and high buildings policy – and my apology for postmodern urban design

- London Sightseeing – a cruise on a River Thames boat

See also: Rem Koolhaas on London’s skyline. Koolhaas remarks that ‘London has always changed dramatically and it’s still is not a very dramatic city. So it can go on. I think that in London whatever you do you do not disturb an earlier coherence. You do not disturb an earlier utopia like in Paris. It can stand a lot of development without suffering’. I read this comment as a polite way of saying that most of London’s riverside is pretty dull, as the above video shows, it has its moments – but not enough of them.