I share the general optimism about Iran’s new President, Hassan Rouhani, and Iran’s future. Many of the country’s problems were caused by western interventions. Others are indigenous. My own experience of Iranians is that they are kind, courteous and peaceful. This has made it difficult for me to understand their demonisation in the west. The new President has both liberal and authoritarian credentials. He gained a PhD in ‘no mean city’: Glasgow. He wear’s a cleric’s clothes and buys from Armani (I do not know how this is possible). If you are also wondering what relevance this has for this blog then I recommend Louise Wickham’s interesting book on Gardens in History: A Political Perspective. Garden design, like urban design, has always been influenced by politics. You can read something of Iran’s last half-century in the above photograph. The design is inoffensive: a little Iranian, a little European, a little modern and not much of anything. So my modest suggestion, assuming President Rouhani reads this blog, is to show your people what you can do for them by encouraging them to draw on the best of Iran’s traditions and the best of contemporary landscape, garden and urban design wheresoever in the world then can be found.

Photo (courtesy jturn) of Park-e Laleh, Jamshīdīyeh, Tehran, Tehran, Iran.

Category Archives: Asian gardens and landscapes

The landscape architecture of Taksim Gezi Meydani 'Park' or 'Square'

Queen Anne asked one of her Ministers what it would cost to stop public access to London’s Hyde park and was told, “It would cost you but three crowns, ma’am: those of England, Scotland and Ireland.” . Public open space should be at the centre of public debate.

The Bosphorus is the traditional boundary between Europe and Asia and also the meeting point of the two cultures which govern modern Turkey: western and eastern. Many Ottoman intellectuals and leaders came from western (European) Turkey. Though born in Istanbul, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s political culture has Anatolian roots. Ataturk, who founded the Turkish republic, was born in Greece and sought to westernise Turkey. So the question, as ever, is: will Turkey look east or will Turkey look west? We can extrapolate the choice to landscape architecture. Looking east, to the Turks’ nomadic past, suggests a lack of significance for permanent open space. Looking west, to the settled lands of Europe, suggests a desire to protect open space.

Though rendered in English as Taksim ‘Square’, the Turkish name is Taksim Meydanı. ‘Meydani’ derives from the Persian word maidan which was used for a multi-purpose civic space. It was not a park (paradaeza in Persian) and it was not usually planted. The uses included markets, parades, festivals, games and camping. This made it a very important place – though the famous maidan in Isfahan has since been laid out as a western park and is not busy. So should Turkish landscape architects look west or east? Both. Topkapi Palace is a good symbol for this: the pattern of its open spaces is that of an encampment, but the encampment has become permanent (as Gülru Necipoğlu, explains in Architecture, ceremonial, and power: The Topkapı Palace in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Cambridge, Mass, 1991).

Well, Istanbul lost its chance to host the 2020 Olympics yesterday for, it is thought, two reasons (1) the brutal treatment of protesters over the proposed development of Taksim Gezi (2) Turkey’s poor record in controlling the use of drugs by its athletes. I give my sympathy to the landscape architects and others involved in Istanbul’s bid and have no hesitation in saying that the landscape architecture of Istanbul is of the very highest quality.

I am pleased to report that London’s park users (photo of the gates of Finsbury Park below) support Istanbul’s park users in calling for the conservation of Taksim Gezi Meydani. We might be able to send protesters if another occupation becomes necessary but we are not considering armed intervention of any kind.

Top image of Taksim Gezi courtesy Alan Hilditch. Lower image Gardenvisit.com

Beijing urban landscape: architecture, planning, design and conservation

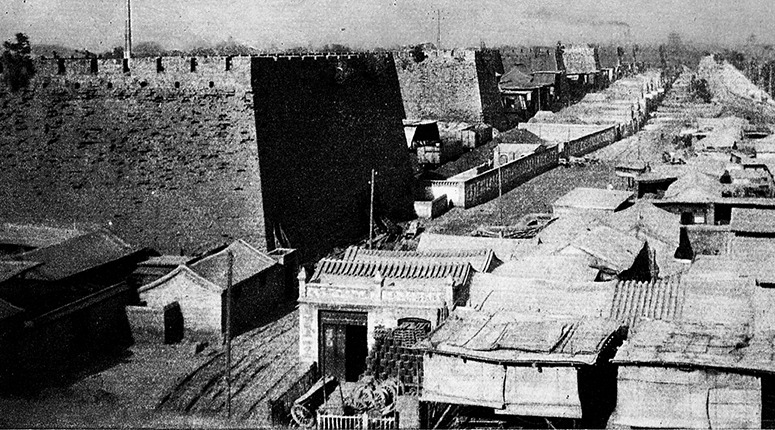

The montage, which is rough, shows a 1914 plan of Beijing superimposed on a recent Landsat image of the Beijing metropolitan area. When the reconstruction of the old city began, after 1949, Chen Zhanxiang recommended that a new city should be built outside the old walled city – so that the central area could be conserved. He had worked with Sir Patrick Abercrombie in London and understood the need for a city to engage in both conservation and development. Professor Liang Si-cheng commented that ‘demolishing the old wall is like peeling off my skin’ (Turner, T., Asian gardens: history, beliefs and design 2010, pp307-8). Beijing’s old walls, which became the 2nd Ring Road, are shown in the below photograph.

Osvald Siren's photograph of the old walls of Beijing, before they were demolished to make a ring road

Were the academics right or were the municipal authorities right? My vote goes to the academics. Central Beijing should have been as well protected from the twentieth century as Haussmann’s Paris. The two capitals have comparable design histories. But, for Chinese urban designers and landscape planners, there were other problems. The old map makes a distinction between the ‘Tartar or Manchu’ Inner City (which contains the Forbidden City and the three Seas) and the ‘Chinese’ Outer City. The Manchus were invaders who spoke a different language. Their walls were a symbol of exclusion and repression, like the Berlin Wall, and were demolished by Chairman Mao’s government. Had the French and British not demolished the Yuan Ming Yuan, Mao Zedong might have done it for political reasons, much as he destroyed Buddhist monasteries. Mao’s position in Chinese history is peculiar. He will always have credit for modernising the country and educating women but, one day, he is likely to receive even more blame for the Cultural Revolution. He will also be blamed for destroying too much of China’s architectural and landscape heritage. So here is my advice to municipal authorities everywhere: find the best parts of your heritage FROM EVERY ERA and apply the most stringent conservation measures possible. This will require landscape assessement technqiues. The ‘blocky landscape’ of early 21st century Beijing will be disliked, sooner or later, but a good-sized zone should be subject to strict conservation measures – including those ridiculuous ‘flower beds’ which line any roads wide enough to have them.

Images of Beijing’s 2nd Ring Road courtesy of ernop and poeloq

Tibetan Buddhist Peace Garden in London

Interesting that it is quite possible to do a good design which is also the wrong design. This is what I think happened in the case of Hamish Horsley’s 1999 design for the Tibetan Peace Garden beside the Imperial War Museum, as explained in the video. Part of the problem is the small scale and obscure location of the Peace Garden vis-a-vis the War Museum. Surely we all prefer peace to war and to not want to see peace tucked away in a convenient, if noisy, corner. I think the scale problem could still be resolved, and cheaply, by placing prayer flag high in the trees – to let them waft their prayers for peace to every corner of the globe.

Mandalas in garden and landscape design

This video is an attempt to involve the forces of nature in making and un-making a ‘flower and sand’ mandala pattern.

Mandalas are diagrams which help explain, in Giuseppe Tucci’s phrase, ‘the geography of the cosmos’. Buddhist mandalas explain the Dharma – the Buddha’s teaching. It is both a philosophical system and a course of action. Sand mandalas are made in Tibet, as part of a monk’s training – and then ‘ritually destroyed’. The outer region of a mandala represents the world and the universe – samsara. It is impermanent. The inner region of a mandala represents nirvana – an ideal condition in which the spirit is liberated from the cycles of death and suffering. Some Buddhists think of nirvana as a real place. Other Buddhists think of nirvana as a state of mind. Mandala diagrams often have Mount Meru, a palace and a palace garden at their centre. The diagram then explains the path from suffering to enlightenment. It is a path which requires, study, meditation and compassion.

For western garden designers, and for non-Buddhists, a fascinating comparison can be drawn with the Neoplatonist/Idealist axiom that ‘art should imitate nature’. In aesthetic theory, it is now interpreted as a call for ‘naturalistic’ and ‘representational’ art. But for most of its history ‘art should imitate nature’ was a call to embody the fundamental essences of Nature in works of art. The principles of optics, for example, were seen as Laws of Nature which could and should be employed in the design of baroque gardens. Under the influence of Christianity, from the time of St Augustine (354-430) onwards, this meant the ideals, laws and principles upon which God’s design for the universe was founded. We could say that a mandala-based design is also ‘an imitation of Nature’ (which Buddhists understand as the Dharma).

Modern Buddhist garden at Kagyu Samye Ling, Eskdalemuir

Most Buddhist gardens are in East Asia – especially Japan – and people therefore have the idea that a Buddhist garden should look Japanese and should probably be a ‘Zen Garden’. This is wrong. I like this comment from the Religious Education and Environment Programme REEP on Designing a Buddhist Garden: The garden does not need to look Buddhist or oriental. Many people, who are not Buddhist, also value such ideals. That the design promotes peacefulness, goodwill and respect for all creatures is more important than things like wind chimes, prayer flags or stone lanterns. If you wish so, you can certainly also include Buddhist and oriental decorations and garden features but, on their own, such decorations are not as important as a design which uses Buddhist ideas.

The Buddhist themes used at Samye Ling are World Peace, Wellbeing and Healing. They also grow organic vegetables and favour sustainability. These are themes which Buddhist Environmentalists have embraced – and which can be read into traditional Buddhism. I support all these themes but have a little regret that a garden of as much interest as Samye Ling does not put more emphasis on core Buddhist principles and philosophical concepts. These include the Four Noble Truths, the Noble Eightfold Path, dependent origination, non-self and impermanence.